By Brent Rogers

The home of the brave, the land of the free, and God bless the American wild turkey! How fortunate for those born or come to the land where a chorus of gobbles electrifies the spring air. The wild turkey, being a native of much of the vast area of North America, has been part of our history as a people and nation. It represents the independence of the American spirit as well as any native fauna, and perhaps only the American Bison has as much historical connection to the Native and later-comers to this land of opportunity. The turkey is the only American animal with “wild” as part of its name, it is a fitting prefix.

Here is the breakdown of Turkey Hunting History through its literature:

- Pre-European: Pre 1620

- European Settlement and Expansion: 1620 to Mid-1800s

- The Lean Years: Mid-1800s to 1920

- Game Farm Turkeys: 1920-1959

- Boom of the Cannon Net and Turkey Populations: 1959-1973

- Rediscovering Turkey Hunting: 1973-1980s

- The Golden Age of Turkey Hunting: 1980s to Present

- The Future

As turkey hunters, we love to tell our stories. As much as it might seem to inflate our egos, it also honors the fallen to memorialize them. There are fish stories and deer camps with fun storytelling around the campfire, but the perfection of the art of storytelling belongs to wild turkey hunters. Turkey hunting is an intensely personal endeavor, yet we yearn to share our joy and misery with others that “get it.”

We celebrate the birds that ride home with us, and we respect the ones that outwit us. We relish those too-fleeting moments in the woods, and it is through stories that we get to relive those moments and fill our off-season with the promise of gobbling turkeys. Turkey literature is an art form, and there are over 400 first edition, first printing books dedicated to telling the story of why and how we hunt turkeys and to relay our triumphs and tragedies. This is not including countless reprints of those books, and an equally vast number of publications on the study and science of wild turkeys, though much of it of value to turkey hunters. Let’s explore the history of wild turkey hunting, how that has been recorded in literature, through which we can go along on turkey hunts past and present.

Pre-European: Pre 1620

We tend to think about history nowadays from a European centric point of view. Though turkeys were new to those arriving in “The New World,” we must remember the Native Americans and turkeys coexisted for many lifetimes. Certainly the turkey was hunted by those native people who made use of spurs for arrow tips, feathers for art and in clothing, and meat to roast and stew. Wingbones likely used as whistles and in hunting well over 1,000 years old have been unearthed. In 2013, faded images in caves of animals hunted and utilized by Native Americans were discovered in Tennessee’s Cumberland Plateau. Among them were a couple of very striking images of strutting and gobbling wild turkeys! The range of turkeys then was impressive, and we know the Mexican natives had domesticated birds, which in the 1500s, were transported around the world and popularized in barnyards and on tables.

Whether native hunters drove some ice age animals to their extinction I can’t say, but I am skeptical about that, as that is more of a western civilization mindset. There is a well-documented symbiotic relationship established between some native people and the wildlife they depended on. There are early accounts of how Native Americans started fires that helped drive game but also provided critical early successional habitat regrowth that would have served insect foraging turkey broods well. Whether intentional or not, it is burn management like we’d do today. Unfortunately, that practice was chastised by early settlers who understandably didn’t want to lose crops.

While there are no published books on turkey hunting from this period, the late Albert Hazen Wright has “done us a solid.” Hazen researched letters, journals, books and official records going back to the 1500s, when European Conquistadors first encountered turkeys in Mexico. He put together a very interesting and detailed chronology of pre and post European colonization interactions with the wild turkey. He published his labor of love in five parts during 1914-1915 as “Early Records of the Wild Turkey” in the ornithological journal “The Auk.” An intriguing historical record of the wild turkey in America, his work is mostly unknown and unappreciated, given the scarcity of the journals. The articles can be accessed online and are well worth your time to find.

European settlement and expansion: 1620-mid 1800s

The turkey was mentioned in the journals of the Pilgrims, including Plymouth colony Governor William Bradford. Of the fall of 1621, he recorded “as winter approached, of which this place did abound when they came first (but afterward decreased by degrees). And besides waterfowl there was great store of wild turkeys, of which they took many.” No wasting time on chasing gobbles during the spring season when planting was crucial, right from the start the Europeans filled their larders in fall and winter. Without sufficient means to preserve much meat, the freezer provided by New England winters, as well as more leisure time after harvest, made fall hunting a reality. The turkey afforded a ready source of protein for the tables of hard-working, hungry people. That is not to say the turkey wasn’t hunted in the spring during this time, it was for sure pursued year round including what was then called “the gobbling season.”

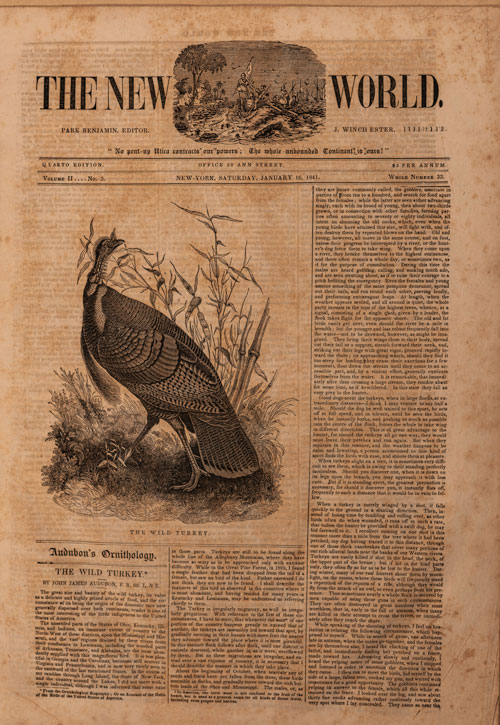

Many people will be familiar with founding father Ben Franklin praising the turkey as a “bird of courage,” and “a respectable bird.” Naturalists like William Bartram, Charles Lucien Bonaparte (a nephew of Napoleon, I might add) and John James Audubon traveled parts of the East and Southeast from the mid-1700s to the early 1800s enthusiastically reporting large concentrations of turkeys in some areas.

It is no mistake that of the 435 birds that John James Audubon published in his 1827 “Birds of America,” the first photo plate was of a wild turkey gobbler! Though some of what Audubon wrote about turkeys has turned out to be bunk, such as his “observation” that gobblers devoured a hen’s eggs to breed her again, the placement and amount of content on the wild turkey sets it apart . As far as I can tell, his notes on the wild turkey in the first volume of his 1832 “Ornithological Biography” are more (much more!) than he wrote about any other bird. He reinforces, “The great size and beauty of the Wild Turkey, its value as a delicate and highly prized article of food, and the circumstance of its being the origin of the domestic race now generally dispersed over both continents, render it one of the most interesting of the birds indigenous to the United States of America.”

At a time when fall hunting was a more recognized practice, he does give insights that some have discovered that, “In spring the hunter calls the Turkeys by sucking air through one of the second joints of Turkey wing bones in a certain way. The sound resembles the voice of the female, and it calls the male…but this requires some skill the cock being quick to detect a false sound.”

No doubt turkeys near settlements would have been attracted to planted fields where there were both ample bugs and waste grain, advertising themselves to hungry working people. These new Americans came bearing new technologies. While the proponents of modern turkey loads might argue it, never was the effect of technology so devastatingly dramatic than going from Native American longbows to European scatterguns. As habitat loss coupled with hunting pressure followed expansion, the process of extirpation was begun.

The Lean Years: Mid 1800s to 1920

The mid 1800s to 1920s were hard years for turkeys, and therefore for turkey hunters. By this time, the game of the plains, like elk, antelope, and grizzly had been pushed into the safety of the mountains from westward expansion. And the remnant of the once-great wild turkey flocks had been pushed deep into large blocks of unsettled land, which in the Southeast was big timber. Turkey populations bottomed out nationwide, at approximately 200,000 birds. Turkey hunting became a mythology to most, something grand-pappy had done, or they might only be familiar with through reading one of the early outdoor periodicals. No doubt this contributed to a “secret society” culture for early twentieth century turkey hunters.

Turkey hunters of the period were typified as being not only guarded about what they knew about turkey hunting and where the turkeys were, but even deviant enough to do whatever it took to “throw the other guy off.” Imagine being a hunter who appreciated the joys of turkey hunting back then, when a successful season might have been hearing a gobble. It wasn’t dishonesty that drove this, but a reality that the next guy in the woods strained a highly pressured resource and invited competition that was good neither for turkey or hunter. It reinforces how fortunate we are today to be able to share our knowledge, mentor others, and invite new hunters into our turkey hunting fraternity! And, that does not replace the need for every hunter to put in the time and wear out the shoe leather learning first-hand the lessons the birds will teach us.

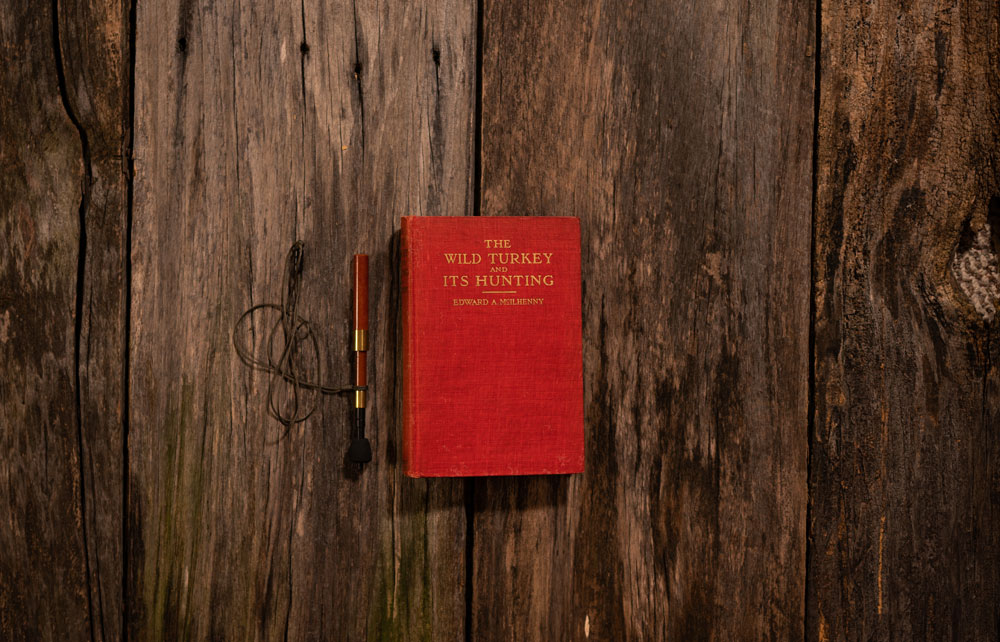

The first book dedicated to wild turkey hunting is an enduring classic, as it covers every aspect of wild turkeys and turkey hunting from a well-learned master. “The Wild Turkey and Its Hunting,” was completed in 1914 by Edward A. McIlhenny; actually it had mostly been written by Charles L. Jordan prior to his death at the hands of a lowlife poacher in 1909. In his introduction to the book, McIlhenny acknowledges, “After Mr. Jordan’s death, through the kindness of John K. Renaud, I secured his notes, manuscript and photographic plates of the wild turkey” thus crediting Jordan.

Although a little early to be registered with the NWTF, the first Grand Slam was likely completed by Charles Jordan in the early 1900s. “I have hunted the wild turkeys on the great prairies and thickets of Texas, along the open river bottoms of the Brazos, Colorado, Trinity, San Jacinto, Bernardo, as well as the rivers, creeks, hills, and valleys of Alabama, Florida, Mississippi and Louisiana.” A man well ahead of his time! In a late 1800s article he wrote for a sporting magazine, Jordan proudly declares “I can but think that the seasons for shooting wild turkeys, as they are fixed in some or most of the states, are not in keeping with the natural seasons ‘made and provided.’ However, I expect to catch thunder from somebody on this score; but I don’t care for all their thunder, so they don’t stop me from shooting old gobblers in March and April.” Just as we see through Audubon’s words several decades earlier, Jordan’s words demonstrate that the enthusiasm and practice of spring turkey hunting was growing.

Thanks Mr. Jordan for speaking up for those without a voice at the time! There it is - the great early debate of turkey hunting. Today’s blogs full of blowhards, the know-it-alls on the bar stool, and the Facebook bullies didn’t invent the battle for who owns the facts on turkey hunting. The first great debate was pitting traditional fall hunters against the upstart spring mating season hunters. Personally, I enjoy both spring and fall hunting, each so different and yet fulfilling a similar need to spend time in the presence of the magnificent wild turkey. Given that turkey hunting is such a personal endeavor, we should allow each other to set our own boundaries, so long as they are legal, ethical and sustainable. We should, however, strive to give turkeys every advantage fair chase can offer. Turkey hunting in its purest form will always be a game of how close, and not how far, and one where more is less; we can take more joy from minimalizing the technological advantages deployed in taking the life of these noble birds.

While most of the early writing we have is on fall turkey hunting, there were several southern states that had seasons during or stretching through spring during the 1800s and early 1900s, even at a time when there were too few turkeys to pursue them year round. Whereas we now argue to close fall seasons, hunters then argued to close spring seasons, when gobblers were more vulnerable.

Game Farm Turkeys: 1920-1959

We can credit the passion of folks in the early to mid-1900s with trying to re-establish a huntable population of wild turkeys. The Pittman-Roberson Act of 1937 filled the funding gap for wildlife programs by taxing sporting arms and ammunition. Then, with the efforts stemming from the 1940 Federal Wildlife Restoration program, states began returning turkeys to their original habitat. They did the best with the knowledge and technology they had. In general, they tried to raise and release pen-reared turkeys from wild-caught stock. At its best, this seemed to provide some seasonal birds for the table, but the survivability of those birds was poor…and often they gravitated back to farms and mingled with domestic fowl. The nesting and brood rearing results from those birds to create sustainable wild populations never met expectations. Henry P. Bridges 1953 book “The Woodmont Story” is illustrative of the amount of time and hope invested in this approach, which many states and hunting clubs were advocating. Alas, time would ultimately prove these efforts fruitless.

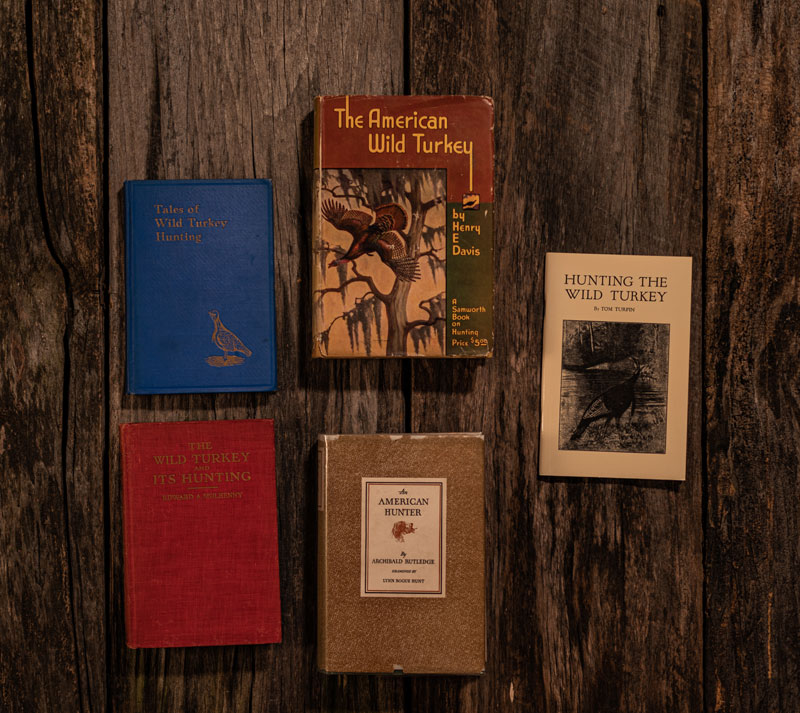

During this period, there were pockets of the country where the wild turkey could still be hunted, and the southeastern states harbored most of them. With the exception of McIlhenny’s book, the turkey hunting stories of the day appearing in sporting journals were often dubious in nature. Turkeys being so scarce, there weren’t any fact checkers…until Henry Edwards Davis came along and called them out in his exceptional 1949 book, “The American Wild Turkey!” There were a sprinkling of trustworthy articles on turkeys in early sporting magazines, those coming from the likes of Charles L. Jordan, Tom Turpin, Simon Everitt, Henry Edwards Davis and Archibald Rutledge, who I call the “Fab Five” of turkey hunting literature. The books they wrote contained turkey-hunting material that has withstood the test of time.

The books of the Fab Five are: “The Wild Turkey and Its Hunting” by Edward A. McIlhenny, “Hunting the Wild Turkey” by Tom Turpin, “Tales of Wild Turkey Hunting” by Simon Everitt, and “The American Wild Turkey” by Henry Edwards Davis. And, although Archibald Rutledge did not write a dedicated wild turkey book, he penned a host of wild turkey stories in many books he wrote in the 1920-30s. The best of those were compiled by Jim Casada in a book he edited in 1994, “America’s Greatest Game Bird: Archibald Rutledge’s Turkey Hunting Tales.”

All five really ought to be required reading, as they infuse the reader with the necessary appreciation, hunting methods and ethics that we should all want to embody. Their reverence for the American wild turkey is something a “real” turkey hunter can respect and should display. The body counts and self-aggrandizing search for social media “likes” drives many modern hunters into a trophy-type mindset that has no place in wild turkey hunting. The pursuit of these graceful, wild haunts of the forest inspired them to pen words that convey the same emotion coming from victories and defeats that we connect to today. They pursued wild turkeys with passion, they learned their language and habits, tested and modified the technology available to them at the time, but all while respecting the birds through hunting them in an ethical, fair chase way.

Boom of the Cannon Net and Turkey Populations: 1959-1973

Sean Connery’s King Arthur, in the movie “First Knight,” declared “There's a peace only to be found on the other side of war.” One of the realities of war is that they drive innovation forward. WWII led us to new wild turkey management tools: the cannon (then rocket) net and radio telemetry. How widely is it known that we owe a debt of gratitude to Herman "Duff" Holbrook, along with a large cast of other contributors, for our modern turkey hunting opportunity? In 1951, Holbrook began using cannon nets as a new method of capturing wild birds, leading to wildly successful reintroductions and expansion into new areas. In addition, radio telemetry began to provide critical data on released wild turkeys. Whether survivability, nesting success, range utilization, hunter impact, radio telemetry of netted and tagged wild turkeys tipped the game in our favor.

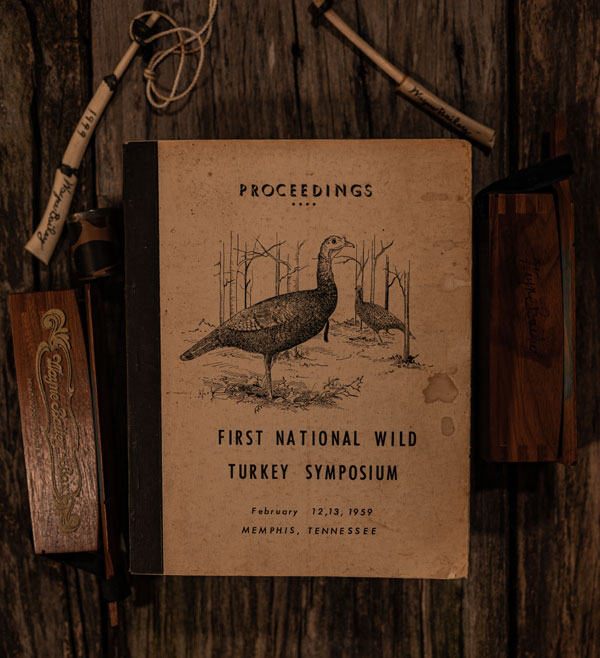

All of these new tools, along with the key cast of characters in wild turkey reintroduction, intersected at the first wild turkey symposium in 1959. Here, the best biological minds in the nation came together to grapple with the challenges of wild turkey restoration. They now had the tools, the funding, the technology and the management discipline for setting and enforcing seasons and laws to get things done. The output of that hallmark moment was printed as “Proceedings….First National Wild Turkey Symposium.” Despite what some may believe about scientific publications (this is not a “turkey hunting” book, but a scientific publication about turkeys), I consider it a must-read.

It is mind-blowing to see the issues these biologists were grappling with and used research to pave the path for modern turkey hunting. The comparison of game farm turkeys to trapped and transferred turkeys was conclusive; game farm turkeys did not successfully reproduce, and virtually all wild caught and released turkeys did. Thank you Henry Mosby, Wayne Bailey, James Powell, John B. Levis, James R. Davis, A.W. Schorger and your contemporaries for your boldness in challenging conventional thought and trying new things. As modern day turkey hunters, we salute you!

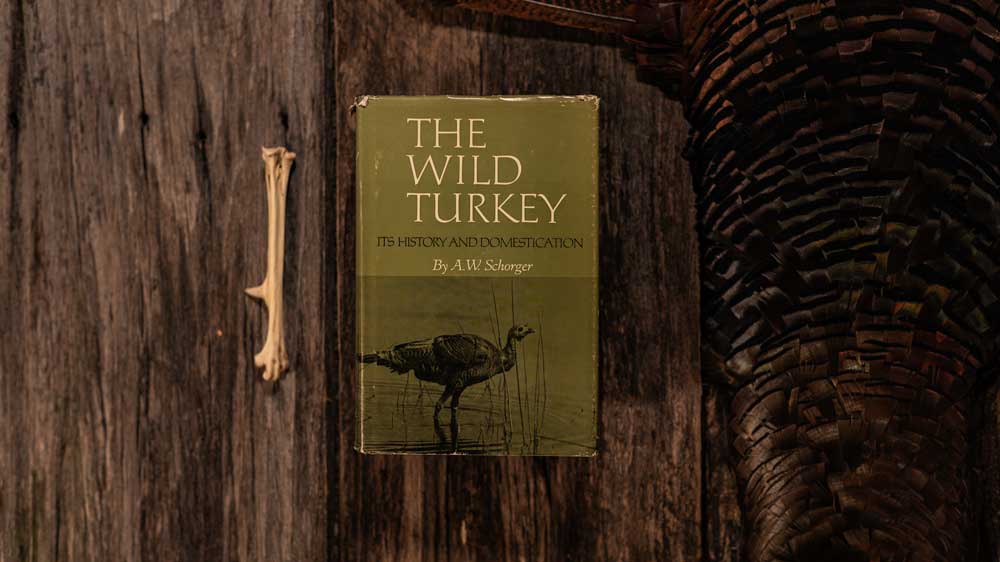

The scientific literature supporting wild turkey study and research up until this time culminated in the publishing in the mid-sixties of the “Twin Tomes,” as I refer to them. This is an acknowledgement of their hefty girth and content. “The Wild Turkey: Its History And Domestication” by A.W. Schorger, with its 624 pages and massive bibliography covered every aspect of wild turkeys imaginable. This ring-worthy volume weighs in at nearly 2 lbs., 9 oz., with less than an ounce of advantage over the book by Oliver H. Hewitt that quickly followed it.

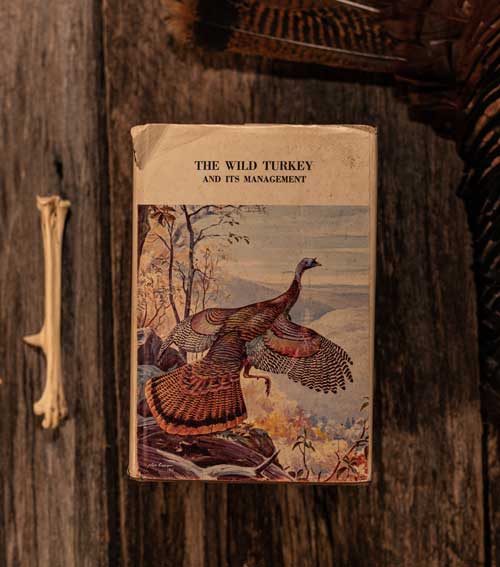

Hewitt’s 1967 tome “The Wild Turkey and Its Management,” is a similar wild turkey anthology at 589 pages. Pound for pound, these are yet the most comprehensive books on wild turkeys you are likely to find, though there are many more modern noteworthy management books worth checking by James Dickson, Bill Healy and others. Notably, both books feature chapters on hunting (and for your call collectors, cowhorn yelpers were covered as good modern callers). Roger Latham, who incidentally had reprinted Tom Turpin’s book in 1966 for Penn’s Woods and wrote his own “Complete Book of the Wild Turkey” in 1956, wrote the excellent turkey hunting chapter in Hewitt’s book. It stands out as being written by a hunter, versus the more stoic and scientific chapter presented in Schorger’s otherwise wonderful book. Henry S. Mosby and R. Wayne Bailey were major contributors to both books, each of whom wrote impactful works of their own. Such is the highly intertwined world and brotherhood of turkey hunting.

Rediscovering Turkey Hunting: 1973-1980s

The 1970s ushered in a steady drip of additional state spring turkey seasons, as the hard work of trap and transfer of the 60s and 70s paid off with expansion of wild turkeys into their former range. It was realized that turkeys didn’t need large, uninterrupted blocks of timber to survive. Rather, border habitat was crucial for them to thrive and expand. Once again, the misty mornings of spring were infused with gobbling turkeys. Turkeys actually exceeded their carrying capacity in some habitats and with the formation in 1973 of the National Wild Turkey Federation, that habitat has been maintained and expanded. Now, a new generation of hunters were rediscovering turkey hunting.

In the 55 years (1914-1969) following that first book by McIlhenny, only 22 books dedicated to wild turkey hunting were printed. These are now rare and vintage books, highly prized by collectors. For those fortunate to obtain and read them, there is a nostalgia and romance to those words penned by our turkey hunting forefathers. The next 10 years alone would match that total with 22 more books on turkey hunting coming in 1970-1979. Up to 1970, books had limited or no content on spring turkey hunting, given two centuries of the fall hunting tradition, which is yet enjoyable and rewarding for those who try it.

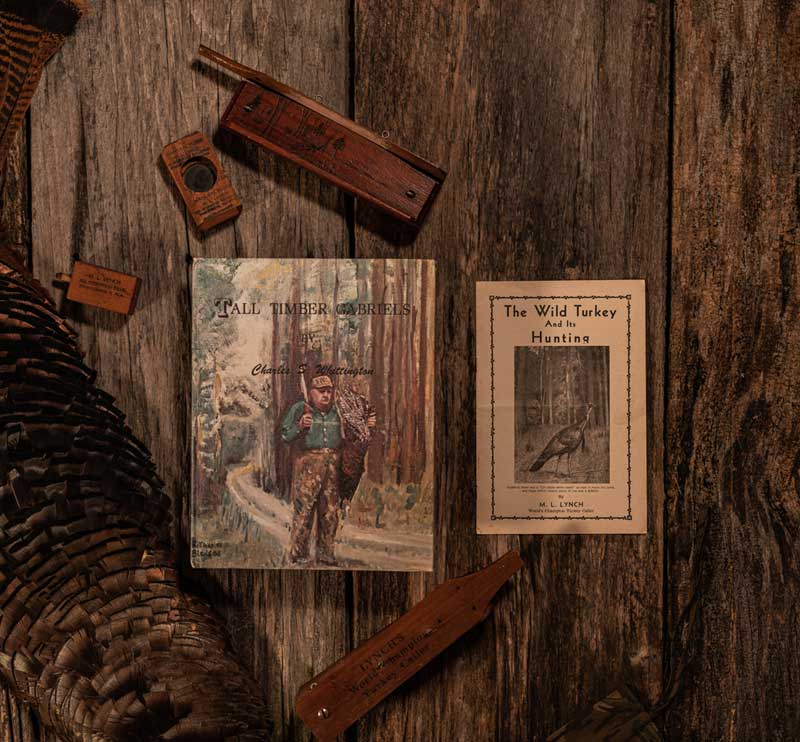

It wasn’t until “Tall Timber Gabriels” by Charles Whittington was printed in 1971 that a book dedicated to spring turkey hunting saw daylight. The subtitle "The Gobblings of a Turkey Hunter” is found inside the book, and sets the book apart from its predecessors, as much of the book is infused with the passion and energy of the spring gobbler. The subject matter of the book clearly distinguishes it from all, or most, earlier works, and without most people realizing it, may contribute to why it is such a fancied and sought after title. The timing of the book is not coincidental, as comes at a time when spring turkey seasons were becoming in vogue in several states following successful reintroductions.

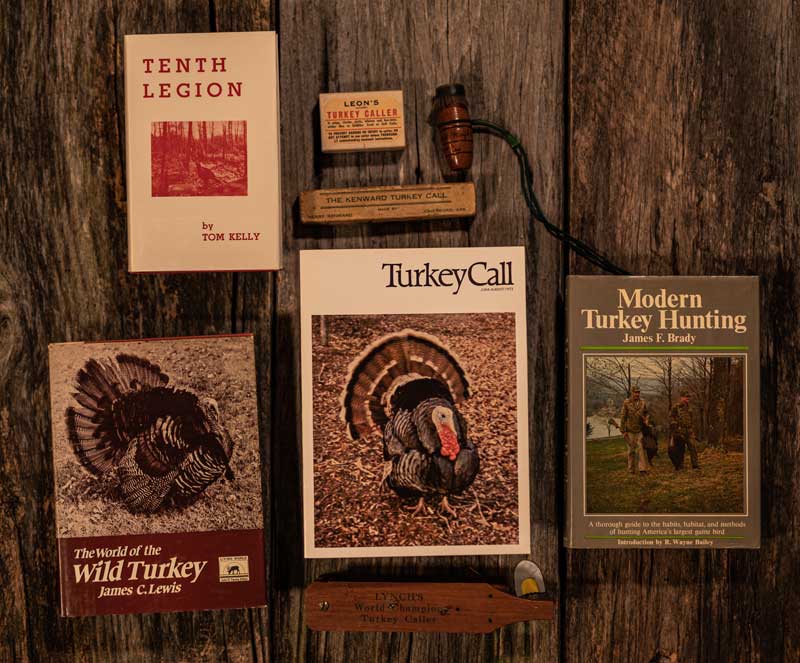

1973 ushered in Tom Kelly’s turkey hunting manifesto, "Tenth Legion." Kelly captured the essence of not how, but why, we hunt turkeys. His words embody why we are emotionally vested and physically committed to match ourselves against such a foe despite the sacrifices we must make. Turkey hunting, for the faithful becomes a lifestyle. It brings a joy we can’t obtain in any other pursuit. We make life choices around turkey hunting, we think about turkeys while we are not hunting, and we love to hear and tell turkey hunting tales. His wit and wisdom are unmatched in capturing our affairs as turkey hunters.

Of the love/hate relationship we have with our success and the success of other turkey hunters, he writes:

“He also knows that when he comes back home empty-handed, as he will do regularly, he will have no satisfactory explanation. He is well aware, for he has met dozens of them, of the numbers of people that will approach him on street corners and in bars and at parties, who will open each conversation with, ‘Well, did you get him yet?’ When he answers no, they will be off and running. They will tell him in delighted tones and in the clearest detail the story of a friend of theirs who has a feeble-minded nephew. Of how this nephew is occasionally allowed home on leave from the state funny farm. How that the last time this poor defective creature was home, week before last, he went out in the woods just behind the house, sat on a log, and with a turkey yelper that was given away as a souvenir by a typewriter company in 1937, yelped twice, and killed a turkey that weighed twenty-three pounds—picked.”

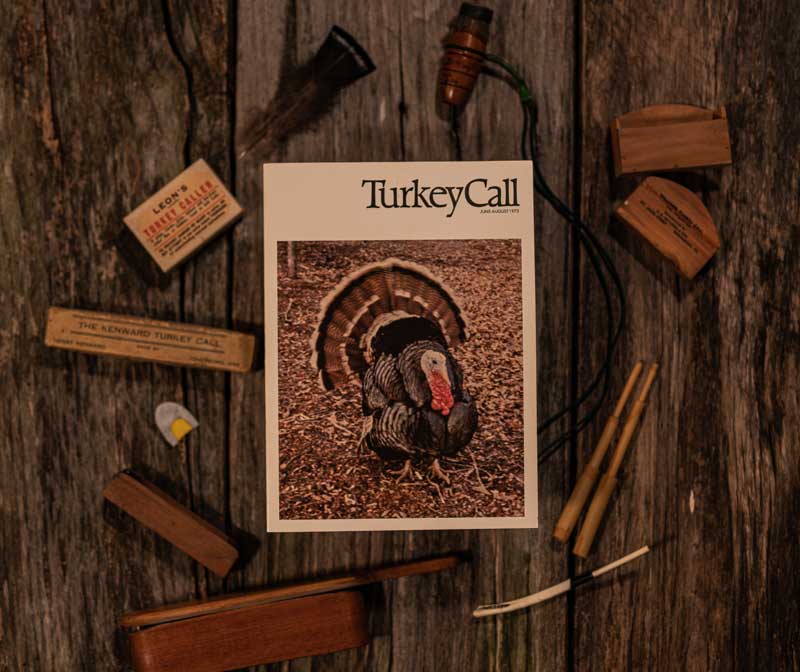

1973 is what I call ‘the year of the turkey,’ given several key happenings that year. A banner year for turkey hunters as well, seeing the publication of “Tenth Legion,” the founding of the NWTF and launch of its magazine, “Turkey Call,” and two other new books for turkey hunters. James C. Lewis released “The World of the Wild Turkey,” and James Brady wrote “Modern Turkey Hunting.” These two books were among the first mass produced (well into the thousands) books on wild turkeys, making them affordable and easy to find today, nearly 50 years later. Lewis provides the biology and behavior of the wild turkey in an every man’s format, easy to grasp and appreciate.

Brady provides a significant how-to book, which given the number of new turkey hunters at the time, is underappreciated today. For those with a keen eye, you will recognize the venerated biologist and hunter Wayne Bailey on the dust jacket.

1980 gave us another gem for the ages in Gene Nunnery’s “The Old Pro Turkey Hunter.” Like the Lay’s chip slogan “Bet you can’t just eat one,” I’d wager that anyone that reads Old Pro once is destined to revisit again and again. Nunnery achieves perfection in the art of storytelling, and future books are still trying to live up to the bar he set. In this era, a new sage of the wild turkey was recognized. Lovett Williams, a biologist who began with studying the Florida turkey, was a young researcher when he had attended the groundbreaking first wild turkey symposium in 1959. He traveled extensively and became the first true expert on the Gould’s and Ocellated turkeys. An accomplished biologist and hunter, Williams also ran hunting camps. His recordings of the wild turkey were groundbreaking. He was a lover of literature, not only writing ten meaty books on wild turkeys, but resurrecting the classics for a new generation. Along with contemporaries Parker Whedon and Larry Hearn, he recognized there was once again an audience for original, timeless turkey hunting books. They formed the justly named 'Old Masters Publishing,’ and in 1984 brought four of the classics to modern turkey hunters: McIlhenny, Turpin, Everitt, and Davis.

When he passed away in 2014, the eulogy made by friends and fellow authors Steve Hickoff and Jim Casada is unparalleled in establishing the impact he had. Steve wrote, “To many of us in the turkey hunting world he was a true legend: an icon, a man whose words on the wild bird we love (and love to hunt) was something close to gospel. You didn’t doubt him. He’d studied the wild turkey all his life, and hunted them as hard as anyone you or I know; not only here in the states, but also in Mexico, where his work on both the Ocellated and Gould’s turkeys was ground-breaking…. It’s safe to say there have been no greater contributions to wild turkey restoration and research than Lovett’s considerable efforts. Rare is the biologist who can convey the true love one has for the bird as well as hunting it.”

Hickoff uses Lovett’s own words to memorialize him best, from his 1989 book “The Art & Science of Wild Turkey Hunting”: “The successful hunter should have the good sense to take advantage of information available in books and magazines and at seminars but to become a seasoned turkey hunter he must also figure out a few things for himself. For me, that has always been the most fascinating part of turkey hunting. Every experience in the woods is full of potentially new discoveries.”

Casada honors him by saying, “Not only was Lovett a longtime friend, but we had hunted together, exchanged ideas and swapped stories, and through the years, he had been the subject of several of my articles. When I needed an unfailing reference source for information on controversial matters — such as turkey behavior, whether to shoot jakes, the biological impact of fall hunting or anything connected with the wild turkey— he was the man. Qualified responses — words such as ‘possibly,’ ‘perhaps’ or ‘maybe,’ and thoughts such as, ‘We need more research,’ or, ‘The jury’s still out on that’ — did not exist for Lovett. When you asked him a question about turkeys, one of two things occurred. He offered a straightforward answer backed by intimate first-hand knowledge, or he simply said, ‘I don’t know.’”

Suffice it to say, Lovett Williams has earned his place as one of one of the greats. No doubt he would have been immortalized in the pages of Jim Casada’s book “Remembering The Greats,” had it not been published in 2012, two years before Lovett’s still too-early death. That book is another one that anyone reading this should quickly seek to obtain. The history between those pages reaches all the way back to Charles Jordan, and covers 27 scions of turkey hunting history. No better book on the history of the great legends and legacies of turkey hunting have I read. Casada is a storyteller for the ages, and brings us the lives, contributions and legacies of the finest of the turkey men who have gone to the “Final Roost.”

All of my Fab Five, and the three Old Masters Publishing founders are covered. He includes turkey men like Ben Lee, Dwain Bland, Jack Dudley, Leon Johenning, Charlie Elliott, M.L. Lynch, Dave Harbour, Frank Hanenkrat, and many others who I have mentioned elsewhere in the span of this history. All were turkey hunting fanatics and lovers of the wild turkeys they hunted. They commanded a use of, and were endlessly searching for better, turkey hunting methods and calls. They all wrote turkey hunting books that will provide inspiration as well as appreciation for “how we got here.”

The Golden Age of Turkey Hunting: 1980s-Present

For hunters fortunate enough to be hunting the last two decades of the twentieth century and first two of the 21st, they experienced the Golden Age of turkey hunting. The peak of the wild turkey population occurred in 2001, at around 6.7 million. 1991 was the first year when spring turkey seasons were finally open in all 49 states with suitable range (Alaska being the exception), the NWTF having completed their Target 2000 program that began in the 1980s with the goal of restoring turkeys to all suitable habitat in the U.S. by the year 2000.

Now a turkey hunting media and product boom begins in earnest. By the early 1980s, there was a ravenous turkey hunting public looking to find ways to “fool ol’ Tom” and satisfy their hunger for both turkeys and turkey hunting. The hunting industry responded with an explosion of options: books, magazines, catalogs, newsletters, records (then audiocassettes and then CDs), and VHS (then DVDs), calls, specialized guns and loads, camouflage and other clothing. Collectors can fill and have (including yours truly) filled rooms with these and all miscellanea pertaining to the wild turkey. These objects document the re-establishment of the turkey and its hunting across 49 of the 50 United States, several Canadian Provinces, Mexico & Central America...even New Zealand! 1980-1989 saw the introduction of 54 turkey-hunting books in those 10 years, more than doubling the volumes that could fill shelves. Mossy Oak arrived in 1986 (a special year for me given it was the same year my father founded his business), and game call companies filled shelves with calls.

Happily, for those of us that relish reading and learning about turkey hunting, the pace hasn’t slackened, but rather picked up. 1990-1999 saw 59 books, and 113 from 2000-2009, 116 from 2010-2019, and 26 already in 2019-2021 (at the time this was written). Self-publishing platforms have made becoming an author incredibly simpler (and cheaper than traditional publishing), and turkey hunters have found it a satisfying way to share their stories.

Old hunting magazines are underrated, at least by those who were born to cell phones, for the wealth of content and quality of authors they sandwich between those glossy pages. During this turkey hunting media boom that began in the 1980s, there were several magazine titles with exclusive wild turkey content: “Turkey Call” (1973-present), “Turkey” (1984-1992, which, in 1987 became “The Turkey Hunter”), “Turkey & Turkey Hunting” (1991-2013, with only annual issues since) and “American Wild Turkey News” (1991-2006; this was the publication of the American Wild Turkey Society, which shuttered when its home office in Sparta, TN was devastated by flood).

In addition, a number of other annual magazines featuring turkey hunting were put out by several outdoor companies from 1981-2007, such as “Aqua-Field Outdoors Turkey Hunting Guide,” “Buckmaster's Beards & Spurs,” “Mossy Oak Full Strut Turkey Hunting,” and “Knight & Hale Ultimate Team Hunting.” The NWTF was churning out a number of spin-off national publications and many state newsletters. There were publications by professional organizations such as the “Professional Turkey Callers Association of America,” and “The National Callmakers & Collectors Association of America” (not dedicated to wild turkeys, but with significant content on turkey callmakers). Even private newsletters (“New England Wild Turkey Hunting” by Wade Bourne, “Tailfeathers” by Bill Privette briefly popped up to fuel the fires of turkey hunters.

I have an extensive wild turkey video collection, and the first (that I have been able to find) videos dedicated to wild turkeys were released in 1985 by Denny Gulvas /Gulvas Wildlife Adventures (“Spring Gobbler Hunting”), Lohman (“Bill Harper Complete Course in Turkey Hunting”), Perfection Turkey Calls (“Spring Turkey Hunting Techniques,” and “Fall Turkey Hunting Techniques”), and PSE (“Gobbler: Spring Turkey Calling in Alabama and Florida with Pete Shepley,” featuring rising star Dick Kirby). The titles are representative of what turkey hunters were hankering for, advice on how to have success at this new outdoors pursuit. In that aforementioned 10 year span of 1984-1993, there were over 80 videos released instructing and entertaining turkey hunters. Many of these brought turkey hunters inside living rooms, to be enjoyed all year, and made new outdoor careers possible as videographers and producers.

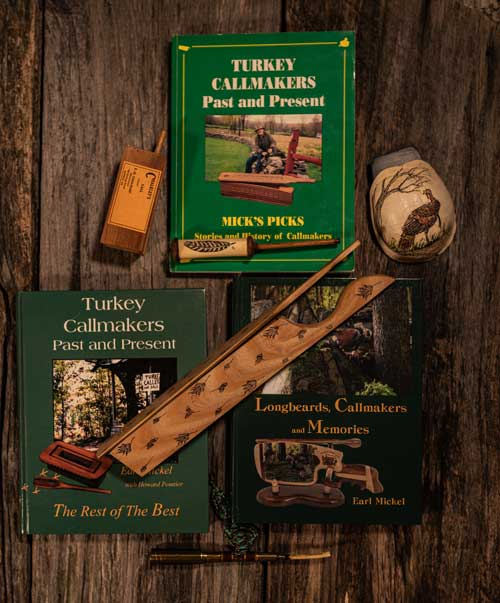

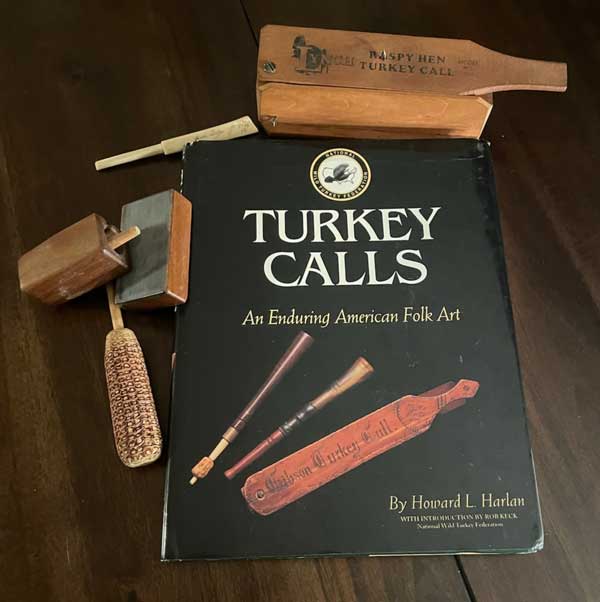

Another phenomenon was triggered with the ‘”Dynamic Duo,” how I reference the 1994 books on turkey calls that revolutionized how turkey hunters viewed, learned about and sought after turkey calls. Two visionary and accomplished men mapped out for all who came after, the brilliance and artistry of those who work at making turkey calls. We get from Howard Harlan a rich history and chronology, and from Earl Mickel a “black book” and ‘”who’s who” of callmakers.

“Turkey Callmakers Past and Present: Mick’s Picks” by Earl Mickel and the two volumes that followed it (not to mention George Denka’s more recent books to carry on that tradition) are akin to turkey call collector’s Bibles. Turkey calls have a practical job of luring our adversary into that window of opportunity for gun and bow, but also an emotional job to provide an experience to the hunter - maybe that is why many of us tend to “call too loud and too often.” Well, that and impatience! Anyone who has hunted predators, elk, ducks or other game where we engage in verbal communication with a wild animal understands the thrill of that process and result. We are making ourselves the hunted! One must study and learn to “Speak the Language,” as Will Primos, of Primos Game Calls, so aptly puts it, to employ such methodology. Mickel captures the essence of the person behind the call in his bios of each callmaker, while also providing the practical information needed for readers to understand key elements of the types and collectability of the calls. He put many callmakers on the map, and many of us still spend countless hours in the pages of those books as we did with the old Sears catalog before Christmas, dreaming of having it all!

Turkey calls have seen a continuous introduction of new types and improvements since Native Americans began using wingbones and reeds. Henry Gibson patented his box call in 1897, and many patents for all manner of calls and parts have followed. However, the bulk of that knowledge is “trade secrets,” residing in the minds and hands of great callmakers, sometimes passed along to a fortunate few.

There is amazing craftsmanship to be found in custom calls, and Howard Harlan illustrates this brilliantly with words and photos in his “Turkey Calls: An Enduring American Folk Art.” Indeed turkey calls are functional art where the call’s user can appreciate the personality and skill of the callmaker. Turkey calls don’t have to be pretty to work, but it doesn’t hurt the experience to have a work of art in your hands when making memories with wild turkeys. Harlan puts together a masterful story of turkey calls and callmakers worthy of a Ken Burns documentary. There are no limits to what make calls collectible, as the beauty is in the eye of the beholder. Some esteem old, vintage calls, others have nostalgia for production calls they grew up using. (Consider just how popular they are; Mike Battey’s design of the parts and assembly of Knight & Hale’s Ol’ Yeller pot and strikers sold more than 400,000 units, and still rides in my turkey vest!) There are collectors who focus on a state, a region, or go deep into one callmaker. Names like Neil Cost, DD Adams, and Tom Turpin all conjure images of turkey call history.

I would be remiss if I didn’t make note of some incredible books that have published in this modern era of turkey hunting. As an avid reader, I am being cautious not to share the dozens of books here that are on my short list (yes, I have a long list of favorites).

- “Home, At Last, Is the Hunter” by W.H. “Chip” Gross came to print in 1993. A fictional book, it is a heartwarming story of making a turkey hunter, and the special relationship we have with our mentors. There is much for turkey hunters to identify with in this pleasant read.

- Joe Hutto’s 1995 book “Illumination In the Flatwoods” is a masterpiece; so good, that it is one of two PBS Nature specials that covers his experiences with imprinting wild creatures. He actually recreated the wild turkey experience for the book. We get to spend over a year, from egg to adult, with Joe and his turkeys, learning the instincts, behaviors and relationships often hidden from us. Information any hunter and lover of turkeys will appreciate.

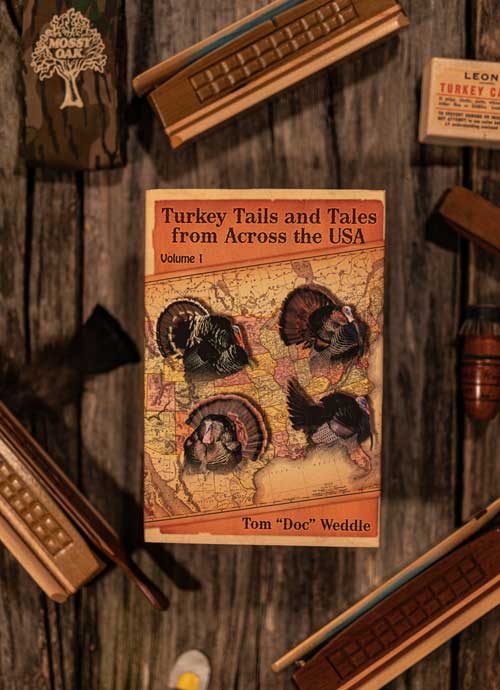

- Tom “Doc” Weddle is my turkey hunting superhero! He lives turkey hunting, and spends February to June chasing turkeys across the country. Unwilling to demean it to a numbers game, he won’t share how many turkeys he’s killed, but along the way he has completed THREE U.S. Super Slams, and is closing in on 4 & 5. He has printed two volumes of "Turkey Tails and Tales from Across the USA" (2013, 2018) and has a third coming. He tells tales with the best of ‘em.

- With a pile of Grand Slams and Royal Slams, Larry Proffitt has pursued the grand bird across the country in both spring and fall. Along the way he sought out the masters of turkey hunting and calling, learning their methods and building an appreciation for those people that he tells in his book, “Letters To My Grandsons.” Novel in its approach, the wonderful book is a compilation of the author sharing these lessons and stories in a series of letters he writes them for posterity.

- Jim Spencer’s name and reputation as a hunter and outdoor writer are well-known and deserved in the turkey hunting world. A self-described “turkey bum,” Spencer says he has been “whipped by turkeys” in three countries and 30 states. He captures the spirit of the turkey hunter, the highs and lows of turkey hunting, and leaves you with the nuggets of wisdom gleaned from individual birds and hunts in his excellent books, "Bad Birds" (2010)and "Bad Birds 2" (2020).

- Ron Jolly has traveled the country hunting, videoing and photographing wild turkeys. He produced 20 feature turkey-hunting videos from hunts in over 20 states, including being the producer for “The Truth Video Series” (Vol 2-8) by Primos. His entertaining writing style puts his readers right alongside him on hunts to experience the thrills, frustrations, successes and failures and his 2020 book, “Memories of Spring,” brings those memories we have rushing back.

The Future

We enjoy an “embarrassment of riches” as the quote goes, related to turkey hunting. We can hunt across the country, we can learn from generations, we can gather and tell our stories. There is no shortage of wild turkey goodies in the form of calls, books, audio and video content. The ability to self-publish and to drop YouTube videos, as well as buy production or custom calls, is virtually unlimited.

Compared to just a few decades ago, turkeys are yet plentiful. However, in some regions, such as the Southeast and Northeast, there is a noted decline. In fact, the first 20 years of the twenty-first century have ushered in an alarming trend with wild turkey populations declining by 15 percent or more in many parts of the country. While weather leading to poor nesting success and poult recruitment is a factor, it doesn’t completely explain the continued decline. At the same time, we are seeing record numbers of licenses sold, and the Covid-19 pandemic inspired more people to escape the drudgery of quarantine and hit the woods. Of course, this taxes the already beleaguered turkey population in some areas creating at least short-term implications of fewer turkeys. I will not attempt to identify the problem; I am not up to the task. However, as the great biologists Wayne Bailey and Lovett Williams would have said, “I don’t know why but I sure would like find out.” Clearly there are multiple variables affecting the wild turkey, including a changing world that they, and we, live in.

There is once again a need for study and management discipline to combat the trend. The NWTF continues to champion habitat acquisition and improvement, and another organization dedicated to turkeys, Turkeys For Tomorrow, has sprung up to increase dollars for turkey research. All hands are needed on deck to address this latest challenge to our native bird. We have a new cohort of wild turkey biologists who are equally capable and are now carrying the torch of truth, much of it yet to be discovered. Just as we never cease to learn while turkey hunting, our researchers, many who are also hunters, like Michael Chamberlain and Brett Collier, are on that quest. State game agencies have begun to acknowledge and address the issue, with a trickle of states changing season dates, bag limits and regulations. As hunters, we must embrace these measures. If anyone can respect the need for the wild turkey to win sometimes, it is the wild turkey hunter.

For those who want to learn more about wild turkey literature and turkey hunting history, I recommend Jim Casada’s “The Literature Of Turkey Hunting: An Annotated Bibliography and Random Scribblings of a Sporting Bibliophile.” This 2011 book not only provides a highly detailed bibliography of nearly every book on turkeys written up to that date, it contains enough information about each for the reader to compile a nice list of titles for toting in the game bag or to enjoy near the hearth on a winter’s eve.

To hear Brent Rogers speak on the history of the wild turkey, listen to the following episode of Gamekeeper Podcast.