provided by the NWTF

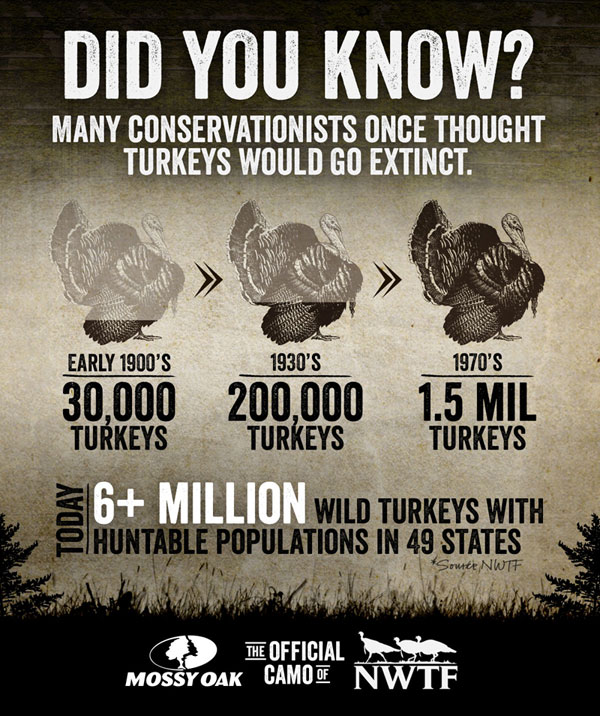

Turkey season is right around the corner, and for most of us in the U.S., going turkey hunting and actually hearing and seeing turkeys is fairly common; actually harvesting one, well, that’s a different story altogether. Regardless, having access to thriving turkey populations is something we get to enjoy as turkey hunters in America today, but it hasn’t always been this way.

By the early-1900s, turkey populations in the U.S. were catastrophically low. Simply seeing a turkey was as rare as hen’s teeth (no pun intended), let alone getting the exquisite privilege of making wild turkey nuggets. There were only thought to be an estimated 1.3 million wild turkeys in all of North America before restoration efforts finally built momentum. To put that in perspective, seeing a turkey then was, on average, over five times harder than it is now and even harder in certain areas.

One project in particular that is a great example of what the National Wild Turkey Federation is doing to actively increase populations is the ongoing Eastern Wild Turkey Super Stocking Project in east Texas. This work is emblematic of the organization’s ability to work across state lines and leverage resources, partners and funds, while also exhibiting a whatever-it-takes attitude for wild turkey conservation. As we head into this spring season, this project is a great reminder, and somewhat of a microcosm, of all the great work that has preceded us the last 50 years and is happening all over the country for wild turkeys and turkey hunters alike.

This super stocking project is a collaborative effort between the NWTF, Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, a few other states’ natural resource departments and private landowners. The project release site is right on the cusp of the Eastern wild turkey’s historic range. A littler farther west and the Rio Grande becomes the predominant subspecies.

Human development, urbanization, lack of ecology research, lackadaisical game laws and a variety of other factors almost eliminated the Eastern wild turkey’s presence in east Texas.

“The Eastern wild turkey once occupied an estimated 30 million acres in Texas,” said Jason Hardin, TPWD’s wild turkey program leader. “However, by 1941 the Game, Fish, and Oyster Commission, predecessor to TPWD, estimated no more than 100 Easterns remained across their historic range in Texas.”

Throughout the middle of the 20th century, the Texas Game, Fish and Oyster Commission (later changed to Texas Parks and Wildlife Department) tried to increase populations by releasing game farm birds. Releasing these farmed wild turkeys was once thought as an effective way to benefit populations, but by about 1980, the growing ecology research conducted by the NWTF and state natural resource agencies substantiated that the most successful way to introduce wild turkeys into an area was through releasing wild-trapped birds.

Despite mounting research and most states exclusively releasing wild-trapped birds as a means for restoration, Texas Parks and Wildlife went against the grain and continued to release game farm birds until 1979.

“This practice likely set the Eastern wild turkey restoration effort back decades,” Hardin said.

The practice of trapping and transferring wild turkeys has mostly remained consistent for the last 40 years and is much what it sounds like: taking turkeys from highly populated areas and placing them in areas with little population. This practice is not easy by a long stretch and requires all parties involved to be ready to work at the drop of a hat.

To capture birds, wildlife managers enter the woods quietly and wait in a blind, much like turkey hunting. Usually the trapping area is well-baited, and once a sufficient amount of turkeys are within range, managers will fire a rocket net that covers the birds and prevents them from flying away. Minus a few technique improvements over the years, this process has proven successful throughout the country and hasn’t changed much over the last four decades.

Managers must act swiftly to untangle the birds, blindfold them and box them up as noninvasively as possible. From there, they run tests to check for avian diseases and other criteria, and then they are shipped to the release site on a commercial plane.

Until about 2003, trap and transfer efforts were done through a strategy known as block-stocking, which entails relocating 15-20 birds at a time and proved a successful strategy for many states. However, this approach was not ideal in east Texas.

“From 1979 to 2003, TPWD used a block-stocking strategy that was successful in some parts of east Texas, but most areas never took hold,” Hardin said. “Texas took a shotgun approach to restocking that often left birds on islands of habitat apart from other populations. This dysconnectivity with neighboring populations resulted in steady declines of the restocked birds.”

During the latter part of Texas’ block-stocking era, Dr. Roel R. Lopez developed a model he referred to as super stocking, which proposed that instead of releasing 15-20 birds at a time, the number be increased to 70-plus birds per release. An ambitious task no doubt. In 2007, TPWD funded research to conduct empirical testing of Lopez’s super stocking model, which proved a viable method for east Texas.

Since 2014, the super stocking method has been providing east Texas with great results — with birds contributed by Alabama, Iowa, Maine, Missouri, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee and West Virginia over the past seven years — and continues to push east Texas turkey populations forward, but it doesn’t happen without a lot of work. In addition to orchestrating the project, actually capturing birds, running tests, transporting birds and releasing them, there is a lot of preliminary work that needs to be done, an area where the NWTF plays a significant role.

“The National Wild Turkey Federation has always supported TPWD’s restocking efforts,” Hardin said. “These days, NWTF’s district biologist in Texas, Annie Farrell, participates in habitat evaluations for proposed release sites alongside TPWD staff.”

In addition to being at a minimum of 10,000 acres of contiguous land, before a super stocking project can be accepted, these proposed release sites have to be awarded with a score of at least 70.

If the land scores 70 or above and falls within one of TPWD’s areas of need, it qualifies for super stockings. If the score is under 70, the landowners and managers are instructed on management practices conducive to improving the habitat for a future evaluation. If necessary, the NWTF and other conservation partners facilitate relationships with the property owner and organizations such as the USDA Natural Resource Conservation Services, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Partners Program, Texas Forest Service and Texas Parks and Wildlife to help improve properties so they qualify for super stocking projects. Along with much of the technical work, the NWTF works from the local, state and national level to ensure all aspects of the super stocking projects are funded and have all resources available.

“The Texas State Chapter of NWTF has a long history of funding the costs associated with getting birds from the trap states to Texas,” Hardin said. “The state chapter has also helped TPWD fund both habitat practices and research associated with these efforts. At the national level, NWTF coordinates with trap states, schedules all flights used to deliver birds to Texas and quickly and efficiently covers any hurdles we may experience along the way with these restocking efforts.”

It’s worth noting that the NWTF truly operates as a federation, with state chapters in every state and many local chapters within each state working tirelessly for the NWTF mission. NWTF volunteers selflessly dedicated their time and energy raising funds to ensure projects like the Texas super stocking and countless others over the last nearly 50 years have essential funding.

While super stocking wild turkeys is a fairly new restoration practice, the results are promising, and they aren’t showing any signs of stopping.

“This is not a short-term effort,” Hardin said. “By focusing our efforts, we can take closer aim, rather than a shotgun approach, at establishing populations within contiguous habitats that will allow for genetic exchange over time. Hopefully we get to a point we can use our own brood stock from past successful efforts to aid in the restoration process.”

“Our ultimate measure of success will be a sustainable spring turkey season in areas currently closed to hunting. However, we are talking about a historic range that once covered 30 million acres. It will take time, but hopefully we can continue to fill suitable habitats with birds.”

There is something that is visually appealing about a turkey being released into a new area, the way it flies off, awkwardly at first but then with vigor shortly after; it’s representative of the evolution of turkey restoration efforts. There is something almost inexplicable about this bird that is so fundamentally American — from how the bird was sought after by the indigenous people of America; to the red, white and blue of its head; to the way that it reveals our past mistakes of taking without giving back. It’s sometimes hard to explain why this bird, an icon of conservation, is so important, but as long as there are the devoted among us who anxiously await those spring mornings filled with the distant sound of a gobble, the NWTF will be around to ensure these moments live on.