Greg Tinsley

Of a winter night in 2022, the Equestrian Statue of Theodore Roosevelt was hauled away from the Roosevelt entryway of the Museum of Natural History. Created by the American master of art James Earle Fraser, the terraced grandiose had held forth from the Manhattan borough of The City of New York for 82 years, inspiring tens of millions of science enthusiasts and lost tourists alike.

Removal of the mammoth bronze – President Roosevelt a horseback flanked by unmounted warrior guides – had been the edict of the city’s political elite and the museum’s operators, who condemned the monument as “too ethnically controversial, too emotionally complex” for the mental consumptions of museum visitors and pedestrians.

The statue’s exodus into exile cost the museum and the taxpayer more than $2 million.

In full retreat, the diminished museum announced its intention to loan the Fraser masterpiece to the Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library in Medora, North Dakota. Honoring the 26th President of the United States (and at 42, still the youngest ever), the “T.R. Library” projects to open on the occasion of America’s 250th birthday in 2026.

For a few years following the sudden and unrelated deaths of BOTH his first wife and his mother – ON THE SAME DAY – Roosevelt rode, roped, hunted, invented cowboy poetry and studied the sparkling firmament from his Elkhorn ranch not 35 miles north of Medora.

Roosevelt never laid eyes on the Fraser monument. Had he seen it, the Medal of Honor Rough Rider may have been moved to the tremendous enthusiasms of his youth, or brought to tears. Certainly, however, the All-American hunter, conservationist and statesman would have made his studied opinion known to all.

Foremost, T.R. was among the most voracious readers humankind may ever produce. His stellar work as a writer had few equals. His famously stirring oratory arraignments, and the actions that backed those words, would chisel his profile onto the granite face of Mount Rushmore.

No world figure ever received the pure tonnage of paper-and-ink accolades and criticisms that Roosevelt bore in life, nor any amount equal to the writings that would trail him in death. Each and every one of his many biographers, to include Roosevelt, the autobiographer, did all agree on one thing: His success as America’s most influential conservationist is what pleased him most.

As a child prodigy in study of the vigorous natural world, the adolescent Roosevelt was himself a puny physical specimen who suffered the nightmare of debilitating asthma. The boy’s earliest activities with nature included written compositions and taxidermy.

At age six, he watched transfixed as the funeral procession of President Abraham Lincoln rattled the avenue below his grandfather’s mansion. His primary schooling occurred at home under the direction of parents who led him to understand that the Christian-based virtues of the stalwart American citizen were all that any one person really ever owned.

For much of his life Roosevelt worked successfully so that his physical condition complemented his hubris. And whilst his wide-eyed entry into local, state, national and international politics was surprising for a young man of his full economic station, it certainly was one of the few jobs that fit the bloom of his energy, his firebrand charisma and the level of servitude that he was called to.

Roosevelt in adulthood had evolved from a Harvard man of means to one who used his uncanny foresight to fight in real-time, and generationally, for every citizen. The cracked skulls he figuratively left in his wake as a Big-Corporate trust buster, as a prosecutor of private- and government-sector corruption, was the crux of the “Square Deal” promise he kept to Americans of every class.

Might, right and, most often, completely disarming: Roosevelt’s efforts as a multinational peacekeeper quelled war between two competing Superpowers, winning the toothy diplomat a Nobel Prize in the early 1900s, back when the seminal Nobel was more than a participation trophy.

Beginning with his creation of the first National Wildlife Refuge in the United States – Pelican Island, Florida in 1903 – it was, however, President Roosevelt, the authentic hot-iron of American conservation, who would set records forever unbroken.

Working closely with his Interior Secretary, James R. Garfield, and his Chief of the United States Forest Service, Gifford Pinchot, Roosevelt created five National Parks and the groundbreaking 1906 Antiquities Act, utilizing the latter to form 18 new National Monuments. Incredibly, he pulled the trigger on the nation’s first 51 bird reserves, four game preserves and 150 National Forests. Public set-asides, protected in perpetuity, of approximately 360,000 SQUARE MILES!

Collaborative intelligence and the Executive Order became his preferred coup de grace for declaring what lands were placed in public reservation for time immemorial. The first 25 American Presidents combined to issue 1,262 Executive Orders. Roosevelt minted 169 for wildlife-habitat reserves from his unmatched total of 1,081. His final enactments featured heavy brushstrokes to his Alaskan masterpiece.

From its purchase in 1867 (at two cents per acre) until the early 1900s, the virginal Alaska territory of the United States remained a time capsule from the millennia. Mostly uncharted and untouched by commercial development, larger than the combined land masses of Texas, Montana and California, the natural condition of The Last Frontier was the personification of wild.

As Roosevelt settled in as Chief Executive, Alaska was completely ripe for natural-resource plundering, and increasingly mechanized Big-Corporate timber and extraction were wringing their hands to do just that.

Roosevelt’s first Alaska protection established the Alexander Archipelago Forest Reserve in 1902. He gigantically added the Chugach and the Tongass National Forests in 1907 (a combined 23.6 million acres). The Tongass alone now features 16 separate wilderness areas.

On February 27, 1909, hours before he would leave the Presidency – with Congress fully prepared to immediately stop Roosevelt’s insatiable appetites for public-land security – T.R. dropped the “Midnight Forests” into law. Those orders preserved the Bering Sea, the Fire Island, the Tuxedni, the Saint Lazaria, the Yukon Delta, the Pribilof and the Bogoslof reservations of Alaska; and the Culebra and the Farallon reservations, respectively, of Puerto Rico and California.

At 65 acres, Saint Lazaria, the showpiece islet of the Alexander Archipelago, was the smallest piece of Roosevelt’s Midnight Run. In contrast, at 16 million acres, the Yukon Delta Reservation was the size of South Carolina. Nevertheless, the predator-free Lazaria, considered the most fascinating Eden on Earth, together with its opulent marine surrounds, supported 500,000 seabirds. One of the recommendations to save Lazaria had come from Louisianan Edward McIlhenny, the founder of Tabasco sauces.

Years following Roosevelt’s death on January 6, 1919 at age 60, Aldo Leupold, another of the country’s most treasured conservationists, offered this contextualized salute to America’s Chief Wilderness Warrior:

“Conservation was a lowly word until Roosevelt made wildlife and forest protection his cause. Wildlife, forests, ranges and waterpower were conceived by him to be renewable organic resources, which might last forever if they were harvested scientifically, and not faster than they reproduced.

“Is my share of Alaska worthless to me because I shall never go there?” Leupold asked rhetorically. “Do I need a road to show me the arctic prairies, the goose pastures of the Yukon, the Kodiak bear, the sheep meadow behind Mt. McKinley?

“No,” Leopold implored.

Author Ronald Tobias, from his book “Film and the American Moral Vision: Theodore Roosevelt to Walt Disney,” definitively observed:

“Roosevelt was the first President to affirm the intercessory power of the state to regulate nature; he was the first President to nationalize nature on a large scale and make the state its guardian.”

Mr. Tobias also reminds his readers of the eight-foot, 230-pound mountain lion that President Roosevelt killed deep in the snow-packed mountains of Colorado. The Boone and Crockett Club, America’s original conservation organization, which Roosevelt co-founded in 1887, held the outstanding tomcat as the World’s Record for 60 years.

Unanimously it is Theodore Roosevelt as Mother Nature’s first-ballot Act of God. He who irrefutably endures as the flagbearer for the original, the most internationally emulated, North American Model of Wildlife Conservation.

In January 1919, a somber Archibald Roosevelt proclaimed: The old lion is dead.

“Death had to take Roosevelt sleeping,” said Thomas R. Marshall, “for if he had been awake, there would have been a fight.”

Photos:

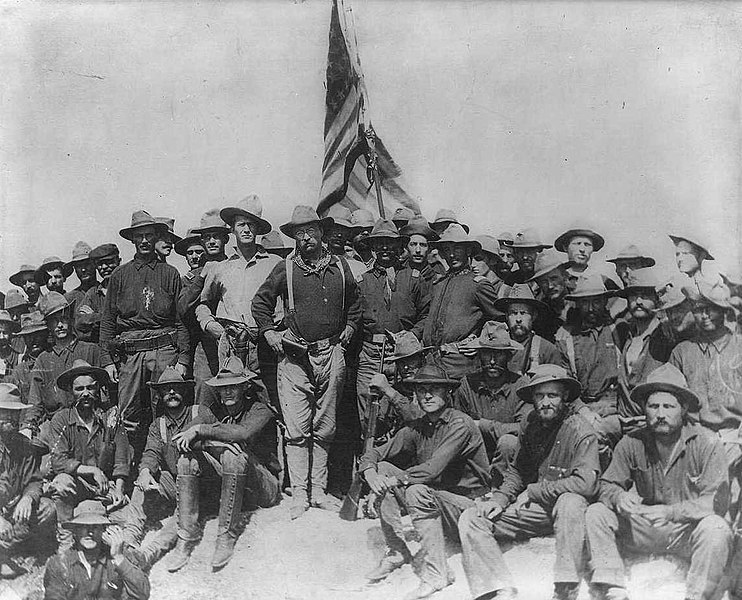

The official Whitehouse portrait of Roosevelt was by John Singer Sargent in 1903, the year America’s youngest President created the first National Wildlife Refuge in the United States. Earlier in life, following the unrelated deaths of both his mother and his wife, on the same day, Roosevelt sat for a “frontiersman” studio photograph before decamping to the solitudes of his Elkhorn Ranch in North Dakota. He would return from the Elkhorn to begin politically crafting a better America, lead the Rough Riders in Cuba and dynamically lift the seminal importance of conservation into world view.