Greg Tinsley

Jay Norwood “Ding” Darling (1876-1962), the Pulitzer Prize winning editorial cartoonist, the hunter, was a conservation legend in his own time, and one for all time.

Born in Norwood, Michigan, Darling’s appreciations for nature began to coalesce on the sun-splashed prairie surrounding Sioux City, Iowa, the place his parents moved the family when he was 10. The young hunter’s first lesson on the importance of wildlife conservation was dispensed by an uncle who corrected Darling for shooting a wood duck during the nesting season.

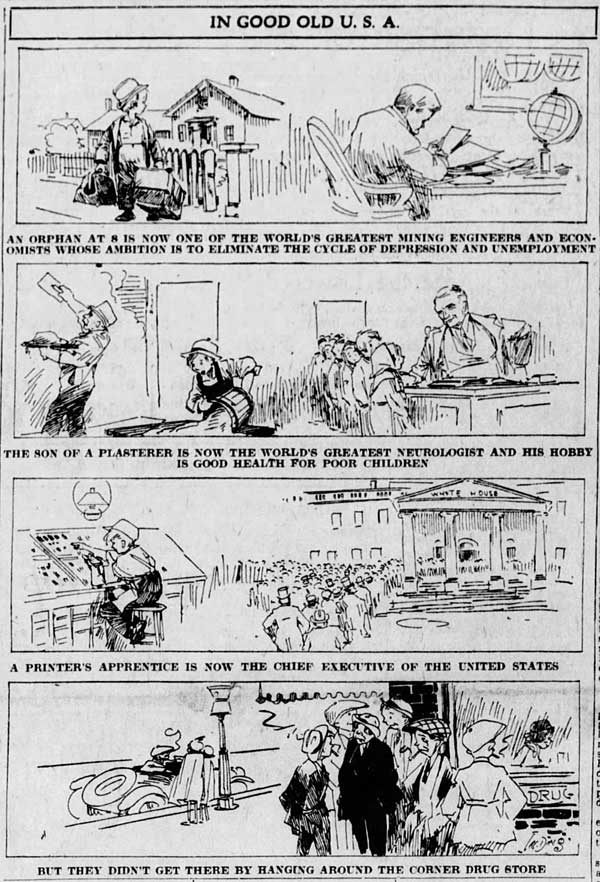

With college behind him, Darling entered the newspaper business in 1900 as a reporter for the Sioux City Journal. But it was his evolution to syndicated editorial cartooning that gave frequency and reach to his voice during a 49-year publishing career, which also included stints with the Des Moines Register and Leader, the New York Globe and the New York Herald Tribune. He developed close relationships with political elites and creative types to include Walt Disney.

American life in the early 1900s, with its Great Influenza Epidemic, Great War, Great Depression and Dust Bowl, didn’t leave much room for the country’s decimated wildlife populations. Nor was there a hard-wearing, science-based conservation agenda to fix that last problem. Perhaps worst of all, the Great Money Grab of the maturing Industrial Age was simply thrashing the rapidly diminished natural resources of America.

Before and after President Theodore Roosevelt went public with his Square Deal manifesto, America’s greatest statesman and hunter-conservationist was inspiring and enabling the birth of a national conservation movement. Eventually, years later, at the bequest of what is today known as the Wildlife Management Institute, an American Game Policy was unveiled during December 1930. This overarching wildlife thesis was the path-forward recommendation from a cadre of top conservationists, headlined by Aldo Leopold, who would author the definitive text Game Management in 1933.

American Game Policy shook the world. It heralded continental-scale wildlife restoration – utilizing trained professionals and science-based research – as the only way to recovery and sustainability.

Back in the heartland, Darling – whose conservation advocacies had him moonlighting as the first chairman of the newly formed Iowa Fish and Game Commission – took heed, answering the big question of “trained pros and research” with a flash of brilliance, which he shared with R.M. Hughes, president of Iowa State University.

What if he [Darling], the University and the Iowa Fish and Game department teamed up to establish America’s first Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit?

The great idea was recognized and executed. Dr. Paul Errington, a protégé of Aldo Leopold, was hired to lead the breakthrough program in 1932.

Darling accepted the invitation of President Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) one year later to direct the Interior Department’s U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (then called the Federal Bureau of Biological Survey). Darling and his Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit now had smooth access to congress, as well as support from almost a dozen land-grant universities.

In 1935, Darling orchestrated a leadership dinner at the Waldorf Astoria in New York City, which he used to pitch the additional needs of the Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit. In the annals of business-and-entertainment this was a World-Series win for wildlife, with the project receiving critical private-sector buy-in from the likes of Hercules Powder, DuPont and Remington Arms.

“If I couldn’t get the support of the sporting arms and ammunition manufacturers, my whole house of cards was bound to collapse,” recalled Darling, crediting the top man at Remington, C.K. Davis, for assuring the full backing of the outdoor sporting industry. By the time the dishes were cleared, the Cooperative Wildlife Research Unit had university, state, federal and private provision.

As a research system of higher learning, Darling’s vision of cooperative wildlife sciences now resides federally within the U.S. Geological Survey. Today there are some 43 cooperatives within the Wildlife Research Unit across 40 states, collectively producing more than 500 graduates. Annually, these well-supported scholars engage in more than 1,000 projects, generating about 365 scientific papers, according to recent accounting by the Boone and Crockett Club and the Wildlife Management Institute.

Ding and the Duck Stamp

Politically, Ding Darling was a charismatic and influential “Hoover Republican” when President Herbert Hoover signed the Migratory Bird Conservation Act in 1929. The law authorized acquisition and preservation of wetlands as waterfowl habitat, but it did not include the all-important mechanism for fundraising.

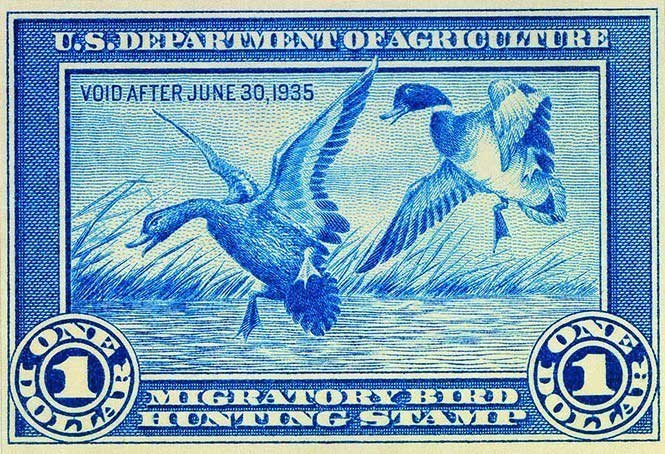

Hoover’s successor, the aforementioned FDR (a distant cousin of President Theodore Roosevelt), already knew what he had with Darling, so his selection of Darling to the blue-ribbon Presidential Committee on Wildlife Restoration was one-quarter political savvy, three-quarters fundraising hubris. Soon, Darling and his colleagues had readied a federal duck stamp program, to include artwork for the first stamp, a Darling original of mallards settling on a prairie wind.

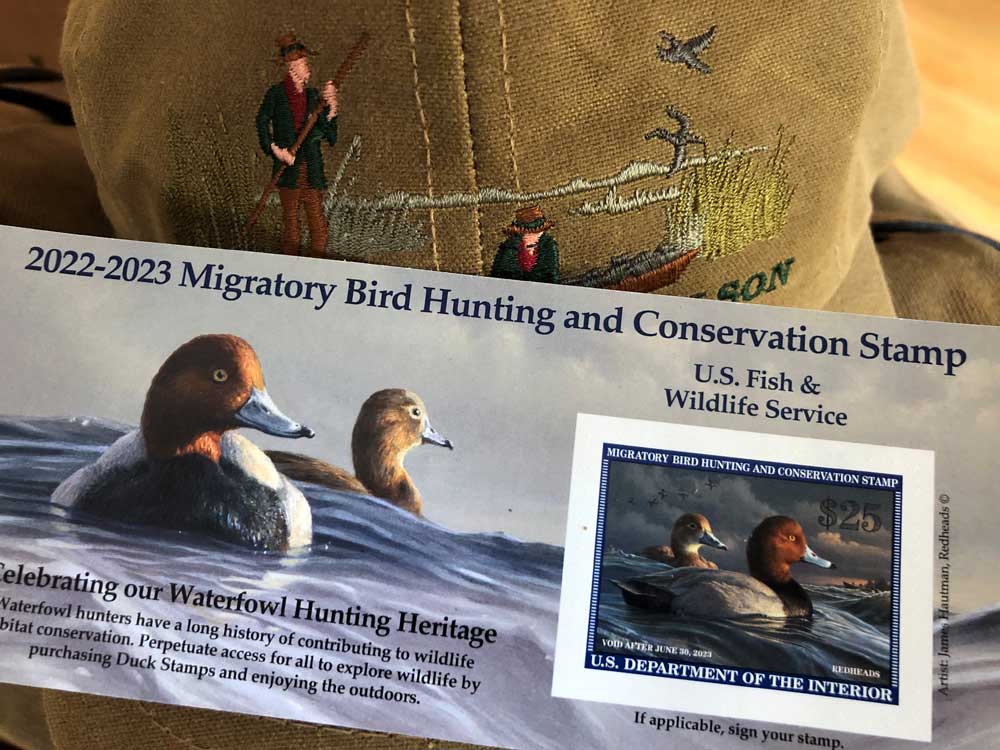

With congressional approval, FDR signed the Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp Act, popularly known as the Duck Stamp Act, on March 16, 1934. Funded primarily by waterfowl hunters, with 98-percent of its proceeds directed to wetlands and wildlife, federal duck stamp monies will overtop $2 billion in total conservation revenue by 2034, the law’s 100th Anniversary.

The federal duck stamp remains the only art competition of its kind sponsored by the United States government.

As a boy, Darling had ridden an Indian pony of Spanish descent behind endless waves of wildlife kicked forth from an ocean of prairie grasses that grew tall enough to brush the horseman’s knees. Much later he would write: "If I could put together all the virgin landscapes which I knew in my youth, and show what has happened to them in one generation, it would be the best object lesson in conservation that could be printed."

Darling’s work as the ultimate startup machine for conservation, and his many honors in this field, also include:

A founder’s role in the 1936 creation of the National Wildlife Federation, as FDR launched what is now known as the North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference. Today, the National Wildlife Federation is administered by the Wildlife Management Institute.

The 6,400-acre J. N. "Ding" Darling National Wildlife Refuge on Sanibel Island in southwest Florida was renamed for Darling in 1967. Darling had personally petitioned President Harry S. Truman to save that irreplaceable habitat from private development, which Truman did by Executive Order in 1945. Throughout the year, “The Ding” is home to more than 240 species of birds.

Darling received the Audubon Medal of the National Audubon Society in 1960.

In the Photos:

Jay Norwood “Ding” Darling, the hunter and the political cartoonist, won a Pulitzer Prize for his strip “In Good Old U.S.A.” His critical role with the development of the federal duck stamp, to include his original artwork, often overshadows Darling’s seminal actions in organizing and funding America’s university-based wildlife sciences. The accompanying Dust Bowl image from a South Dakota farmstead in 1936 illustrates a host of smothering issues faced by Americans and wildlife at the start of the last century.