Greg Tinsley

Were it not for the brilliant influences of Aldo Leopold (1887 - 1948) the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation may never have achieved worldwide preeminence. Further, without him, wildlife conservation – featuring the activism of civilian hunters and fishers – likely does not survive the modern anti-hunting movement, which found its disingenuous voice in America during his lifetime.

Within the all-important scientific and political communities, Aldo Leopold was exactly the right genius, at precisely the right place and time.

He was a bowyer, an arrowsmith and a lifelong hunting archer. He wore a pistol and handled rifles as an early wildlife professional, and for all his life he experienced the wing-shooting joys of waterfowl and upland birds. Within this soul’s most complete picture – son, husband, father, master campfire technician and wilderness champion – there is no escape from the preponderant meaning in Leopold the hunter. The clear truth of which remains in transparent celebration through The Aldo Leopold Archives at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the resource for the historical photography that accompanies this telling.

The Magna Carta of Wildlife Conservation

Game Management, professor Leopold’s 1933 textbook, established the holistic science of wildlife management, casting his place as the nation’s foremost authority on the subject. "The art of making land produce sustained annual crops of wild game for recreational use," stands as the author’s topline proposition.

It was, however, his breakthrough bestseller, A Sand County Almanac, published posthumously in 1949, that allowed the studied thoughtfulness of a citizen hunter – and world-class writer, philosopher, naturalist, scientist, ecologist, forester, conservationist and environmentalist – to forever resonate among academia and a conscientious public.

Translated to more than a dozen languages, Sand County journals Leopold’s efforts to restore an 80-acre Wisconsin farm to some semblance of God’s original glory. Long denuded of native forests, grasses and forbs – with most of its once rich topsoil reduced to sand – his project at purchase was a wrecked and weathering country.

The book traverses the great ecosystems that the clinically observant and well-schooled Leopold had been privileged to study during his distinguished career, returning time and again to the blown-up piece of Wisconsin sand, where he chronicles the labors and the pleasures of landscape restoration. In it, while giving final form to his all-important land ethic, a term he originated, he writes: “A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise.”

He mirthfully noted that conservation guidelines in those times could be pared to: “Obey the law, vote right, join some organizations, and practice what conservation is profitable on your own land; the government will do the rest."

In his verses about the land ethic and ecological conscience, Leopold wrote simply that: "Conservation is a state of harmony between men and land."

Sand County is accessible science wrapped in a poignant love story – beautiful, lively, austere, symbolic and haunting, which, as a work of literature, competes well against any non-fiction thus produced on American soil.

Leopold was a fierce champion of wilderness, to include its supreme value to mankind in an ever more populated world. "Of what avail are forty freedoms without a blank spot on the map?" he asked.

Born to a family of education-minded German immigrants, Leopold’s outdoor insights were honed by the ancient river bluffs surrounding his birthplace in Burlington, Iowa. His father, Carl, a desk-maker, began introductions to woodcraft and hunting in the “extreme-youth” phase of Leopold’s childhood. Each August, the family also vacationed therein the pristine forests of Marquette Island on Lake Huron in Michigan.

With an explorer’s heart, young Leopold embraced nature with analytical inquisitiveness, positioning himself among the graduates of the forestry school at Yale University. The curriculum, among America’s first, had been established in 1900 through donation and input by Gifford Pinchot, another founding member of America’s conservation dream team.

After college, as a new recruit to the young United States Forest Service (USFS), Leupold labored in Arizona and New Mexico – District 3 – from 1909 until 1924. He worked initially in predator control, which profoundly organized his perspectives of ecosystems. He also developed the original management plan for the Grand Canyon and proposed the Gila Wilderness Area in New Mexico, eventually the first such set-aside in the United States.

At the close of that period, Leupold accepted association with the Boone and Crockett Club, America’s first wildlife conservation organization. B&CC had been chartered by the likes of Theodore Roosevelt and George Bird Grinnell in 1887, the very year Leopold was born.

He lived in Wisconsin thereafter, first as a director of the USFS Products Laboratory in Madison, before accepting appointments to become the first Professor of Game Management at the University of Wisconsin and director of its arboretum. He wrote Game Management, traveled with a select team of USFS personnel to study German forestry and wildlife management techniques – and bought the farm that is the tortured soul of Sand County.

With the first edition primed for the printer, cardiac trauma took Leopold as he fought wildfire from the farm of a neighbor.

The greatest legacies of Aldo and Estella Leupold, married 37 years, were their kids, who followed their trailblazing father into teaching and the sciences of nature. They were: Aldo Starker Leopold (wildlife biologist and UC Berkeley professor); Luna B. Leopold (hydrologist and UC Berkeley geology professor); Nina Leopold Bradley (researcher/naturalist); Aldo Carl Leopold (plant physiologist and Purdue University professor); and Estella Leopold (botanist, conservationist and University of Washington professor emerita).

In 1982, the family established the Aldo Leopold Foundation of Baraboo, Wisconsin, whose mission is "to foster the land ethic through the legacy of Aldo Leopold." The foundation owns and manages the original Aldo Leopold Shack and Farm and more than 300 surrounding acres. It is headquartered at the Leopold Center, where it conducts annual educational and land stewardship programs, providing interpretive resources and tours to thousands of students and visitors.

The Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute at the University of Montana, Missoula was established by the USFS in 1993. It is the only research group by the United States that is dedicated to the developments and the disseminations required to improve the management of wildernesses, parks and similarly protected areas.

Intellectually, Leopold closed the book on the Armageddon-scale wildlife slaughter of Manifest Destiny, of the unbridled destruction of wildlife habitat by the Industrial Revolution, with simple, signature prose:

“In short, a land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow-members, and also respect for the community as such.”

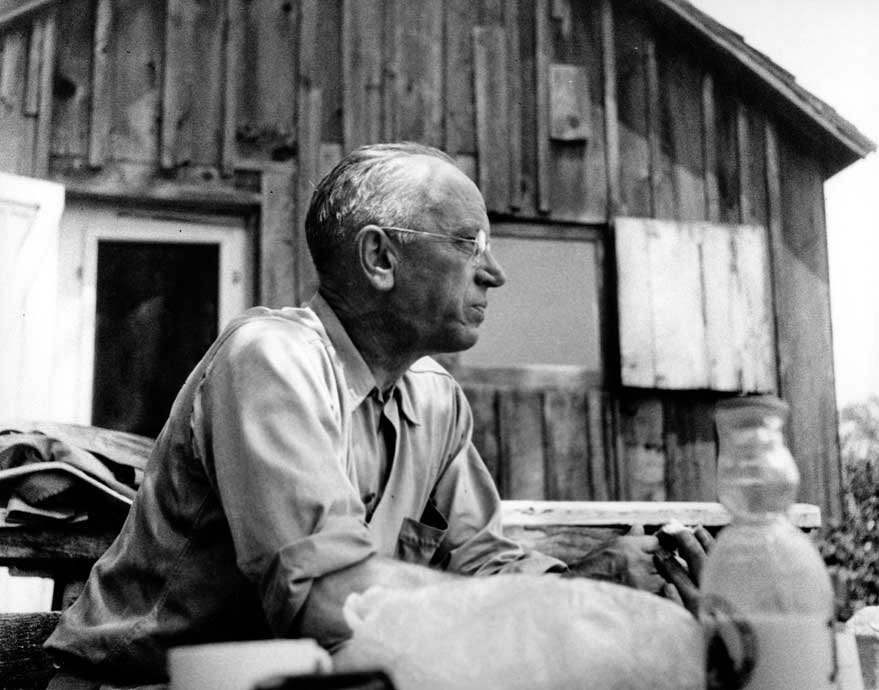

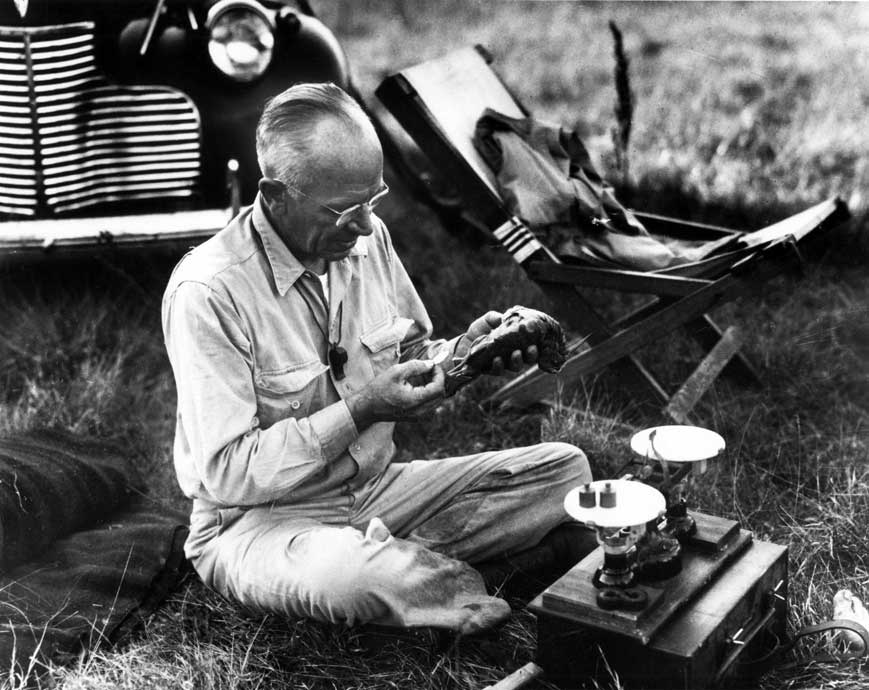

In the photos:

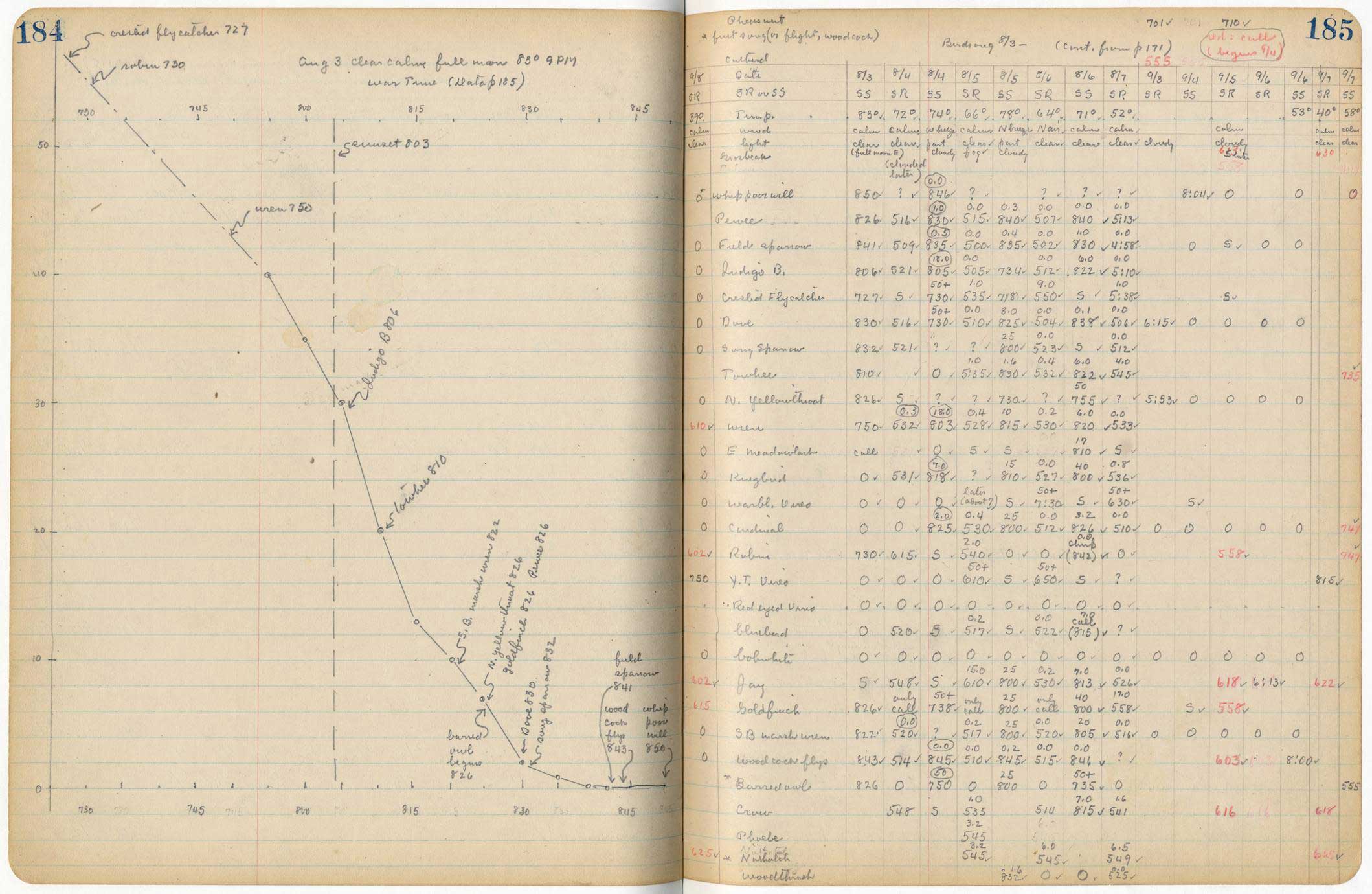

Leopold combining business and waterfowling pleasure near the Bosque Sandbar of the flooding Rio Grande in New Mexico. His meticulous observations were scientifically legered, regularly including the weights of collected samples like these woodcocks, on their way from a jeweler’s scale to a hot skillet. His ultimate appreciation for the respite found in his small slice of the Wisconsin sandhills seems to have exceeded all of the places that he traveled to, and lived among, including the monumental Gila Wilderness.