Brent Birch

The following is an excerpt from the book “The Grand Prairie: A History of Duck Hunting’s Hallowed Ground” detailing the early days of green timber duck hunting in Arkansas’s famed Stuttgart region.

As rice farming became widespread in the early 1900s, ducks numbering into the millions found the fertile feeding grounds of Arkansas. The Grand Prairie region of the Delta has a subsoil layer of clay that lends itself to the growth of shallow-rooted plants, so it is perfect for rice production. Word soon traveled around North America and the rest of the world that ducks were piling into the state in huge numbers, thanks to rice growth and water control efforts. Stories began filtering out of the area of spectacular hunting and heavy straps of greenheads more the rule than the exception. Duck hunters wanted to go there and see it for themselves. Public hunting areas were years away from being established, and then they were difficult, to say the least, for outsiders to navigate and find success on. So the basic economic rules of supply and demand took hold, and private landowners began outfitting hunters. Duck hunting became a business.

And business was good. Folks from every walk of life came to hunt, especially the rich and famous. Baseball Hall of Famer Ted Williams loved to hunt the area; Dallas Cowboys’ owner Jerry Jones owns land there today. Demand grew for hunting supplies, so retail establishments branched out into sporting goods. Duck calls, shotguns, ammo, clothing—it was all needed then and now. Families flourished by pioneering opportunities resulting from the simple fact that ducks love the combination of rice, water, and flooded woods. Opportunists created businesses and brands that sustained the ebbs and flows of duck season and the test of time.

Slick McCollum’s Stuttgart Hunting Club

No history of Arkansas duck hunting as a business is complete without an in-depth look into the McCollum family. They have been pivotal in the development and promotion of the Stuttgart area for duck hunting. Their roots run deep into every aspect of the duck hunting business, from guiding hunters on lifetime experiences to providing the gear they use to do it. Thad McCollum was instrumental in Stuttgart becoming the home of the World Championship Duck Calling contest. Other family members would develop hunting destinations. The McCollum family tree splinters in many directions as does their influence on the Grand Prairie

.

The duck hunting McCollums can be traced back to one man, M.T. McCollum, Sr. Between his two marriages he had eight sons in all. The work of these men would be foundational in taking the local duck population from a nuisance to a profit center. Of all the brothers, Otis had the most impact on turning duck hunting from sport to business with his development of 7,000 acres into a duck-hunting wonderland. He was a visionary, a man ahead of his time, creating the Bayou Meto–Big Ditch area, a vital project crucial to water control. He loved the green timber hunting and knew that a levee system was the only way to guarantee water for ducks during the season. And build them he did, using a simple sight level and whatever equipment he could find. All of this movement of earth was accomplished just after World War II, requiring tremendous dedication to make it happen.

Of course, all of this cost money, so in order to recoup his costs, Otis became a guide. He charged up to ten dollars a day—the equivalent of $250 in 2017 currency—but then a dollar went much further. As hunters experienced glorious mornings with thousands of ducks on the wing, word spread and demand grew. Stuttgart was the place to be, and Otis McCollum put hopeful waterfowlers on the ducks. Hunters kept coming with money to burn, boosting many aspects of the local economy. Soon it became evident that there was money to be had, and Roy McCollum wanted in on the action. He had partnered with Roger Crowe and Wallace Claypool to form the Stuttgart Hunting Club on 1,500 acres of prime land. Seizing the opportunity that Otis had started, he bought them out and developed the land to attract ducks and paying customers.

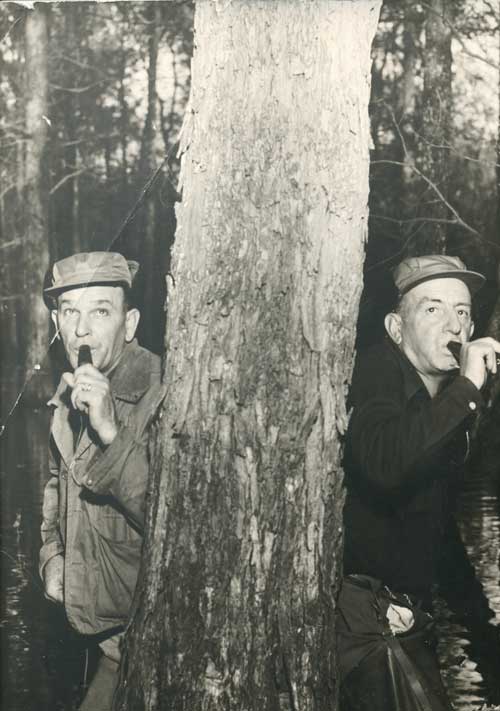

And attract ducks it did. Greenhead mallard drakes parachuted through the treetops, to the delight of hunters from all around the country. When Roy passed on in 1947, he left the club to his son, Kenneth. Not many folks called him by that name; he was simply known as “Slick.” He had won the World Championship Duck Calling Contest in 1939, so his prowess as a duck hunter and renowned caller was already solidified when the land became his. Slick McCollum’s Stuttgart Hunting Club was born.

Early on, it was leased out for a 10-year span to a group from Texas. But they never hunted during the week, so Slick had the freedom to expand the land into commercial day hunting. He created new holes and separated the property while adding a reservoir to ensure water. Improvements continued to mount over the years, and when the lease ended, he was ready to expand the operation. Soon hunters were flocking in like ducks to hunt at Slick’s. He turned to family members and friends to serve as guides, and most of them stayed with it until passing or age prevented them from continuing. J.W. McCollum guided for Slick’s from 1970 to 2003, when he finally hung up his calls at the age of eighty.

Today Slick’s is a vibrant hunting destination still going strong and attracting duck hunting enthusiasts from all over. In a normal season, around 1,100 hunters stay there and enjoy first-class accommodations and world-class hunting. It encompasses 1,850 acres today, 1,200 of which occupy flooded green timber, the big draw for any duck hunter traveling to the Grand Prairie. Farmland and a 150-acre reservoir round out the property, giving it everything a duck would want to spend the winter.

The place remains in the McCollum family and is managed by descendants Brad and Jay Moss. They are dedicated to making Slick’s special, as Brad explained. “If we ever turned the operation over to anyone else, you would lose that family feel. We always strive to treat people as we would want to be treated.”

Brad described a typical hunting trip at Slick’s:

“Guests arrive the day before their hunting trips begin and settle into their lodging for the duration of the stay. That night they have a nice meal at the lodge, followed by a full breakfast the next morning. Guests usually get up around 5 a.m., as we have plenty of time to get where we will be hunting as all of the areas are close by. After breakfast, they meet with their guide and head out for the morning. Arrival time back at the lodge varies depending on the hunting, but no party stays out past 10:30. We let the birds rest in the afternoons.”

Slick’s has a loyal following, as Brad explained, “From opening day to New Year’s Day in the 2016–2017 season we only booked one new party. Provide consistent hunting and a great atmosphere, and people want to come back year after year.”

Another prominent family name in the Grand Prairie duck business is LaCotts. Early family members migrated to Arkansas Post, the first European settlement in the lower Mississippi River Valley and a French trading post on the lower Arkansas River. This was long before Arkansas achieved statehood, and the area was the first capital of the Arkansas Territory before being supplanted by a town called Little Rock in 1821. This was a wild place where Quapaw Indians traded furs and other goods with French, Spanish, and American trappers and merchants. The people were hardy and self-reliant; a perfect mix of ancestry for men who would make duck hunting the river bottoms a way of life.

LaCotts’ Duck Hunters Paradise

Clarence Elmer LaCotts, Jr. started life near DeWitt in 1914; most folks knew him as “Tippy.” His father, Elmer Sr., found some land on Mill Bayou—a part of legendary Bayou Meto and a mere five miles from DeWitt—to his liking and set out to improve it for duck hunting. This relatively small parcel of land, at 270 acres, had what the ducks wanted and thus became a draw for the hunters who paid Tippy and his father to guide them to heavy straps of birds on a regular basis.

Some of these hunters had notoriety, Nash Buckingham being one. Nash had moved over to Arkansas from Beaver Dam in Mississippi for the majority of his hunting. Another of Tippy’s clients was Edgar Monsanto Queeny, who tried to buy his Mill Bayou paradise. LaCotts wasn’t selling, though, and this led Queeny to establish his iconic wildlife retreat, Wingmead.

Eventually Tippy LaCotts decided to lease his land to a group out of Memphis, and day hunting ceased. But by then the LaCotts legacy had been firmly established in the Arkansas duck guiding trade. This was after World War II, and Tippy built a lodge on the property in 1951, now known as the Mud Lake Club. Memphis bankers and businessmen leased the land and formed the club and used it for over three decades. There came a time, however, when LaCotts wanted the land back to take his family hunting, given his grandsons were old enough to partake.

Sid “Deuce” LaCotts is one of those grandsons. “My dad died when I was young, so my grandfather became our father figure,” Deuce explained. “My brother and I spent a lot of time with him. He taught us about hunting and fishing, about the woods and respecting the land and the animals. We were lucky, of course. I never hunted on public land until much later. My childhood was spent hunting the green timber at Mill Bayou. Guess you could say I was spoiled.”

Deuce, who’s called that because he is Sid Jr. (and his son is called “Trey” for the third), revealed where his grandfather got the nickname Tippy. “When he was in the first grade he got up in front of the class and sang a popular song with soldiers in World War I called ‘It’s A Long Way to Tipperary.’ From then on, he was known as Tippy,” he said with a grin.

Deuce is a guide in his own right in addition to his regular job moving earth with heavy equipment. His outfit is called LaCotts Baker Guide Service, focusing on goose hunting for specks and snows around Stuttgart and DeWitt.

“I started out guiding for ducks, and geese were just something to do for my hunters in the afternoons. As the years passed, I decided to move away from ducks and just run goose hunts. Most of my clients come from other outfits, they hunt ducks in the morning and meet me at a predetermined location for an afternoon goose hunt. We do pretty well, and the money is good. My grandfather wouldn’t believe what people pay these days to hunt. Tippy charged between $7.50 and $10 for a morning in the woods. Man, how times have changed.”

Lost Island Hunting Club

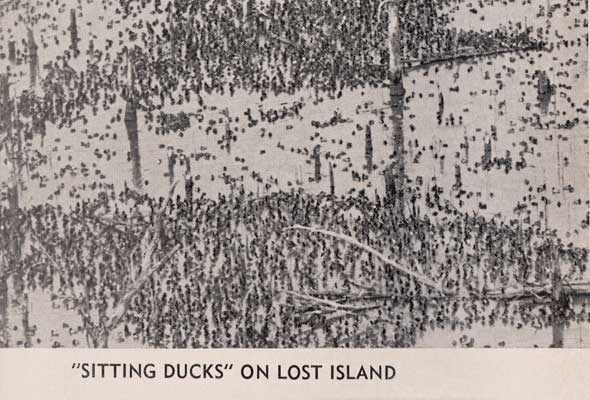

There are many others who took advantage of the excellent duck-hunting habitat of the Grand Prairie. Mr. Vic Bischoff began putting together the 1,020 acres of neighboring properties that would become Lost Island Hunting Club in 1920. It would take four years to get it all together and ready to hunt. The name comes from a pattern Bischoff observed when talking to landowners about purchasing their tracts. They all had similar stories about the large tract of woods, saying, “It’s back in there where so-and-so got lost.” Thus, Lost Island made sense when it came time to name the place.

Moving forward to 1968, the land was purchased by Earl Durdy Farms. Earl’s son-in-law, Carlos Carter, took over the management of the club. “The membership route was chosen over guiding day hunters then, and the next twelve years passed in this manner. Then in 1980, a group calling themselves the Pine Bluff Recreators leased the land for the next 30 years,” he said, recalling club history.

Brothers David and Wayne White often served as guides for the men, and they formed a bond over the decades. Carlos remembers one special morning in particular:

“David owned a retriever named Daisy that was a dynamite dog and loved by all who hunted with her. When she passed away he loaded up some shells with her ashes and passed them out one morning before a hunt without telling anyone they were not normal loads. The first group of birds comes in, shots are fired, and nothing falls. Everyone thought they had missed, but they were scattering Daisy’s ashes in her favorite spot.”

In 2010, Lost Island switched gears and became a day hunting operation. A big plus for hunters traveling there is the location; the front gate is literally in sight of the Mack’s Prairie Wings parking lot.

“They come from around the country to hunt with us,” Carter said. Hunters from California, Georgia, South Carolina, Alabama, and other states visit every season. “We hosted 464 hunters in the 2016–2017 season over the 60 days. Many folks come back year after year, and you develop relationships with people. It’s a pretty good job for a guy who married the boss’s daughter,” he concluded with a smile.

For more chapters and information on Arkansas' famous duck hunting region, grab a copy of "The Grand Prairie: A History of Duck Hunting's Hallowed Ground."