Brent Birch

The following excerpt is from the book “The Grand Prairie: A History of Duck Hunting’s Hallowed Ground” by author and publisher Brent Birch. From the first rice crop grown in 1904 to the famed green timber, the book contains over 340 pages detailing the people, places and events that earned the region the title of "The Duck Hunting Capital of the World". The book is available in hard cover as well as a signed and numbered collector’s edition at www.arkansasgrandprairie.com.

Dixie Mallard Calls

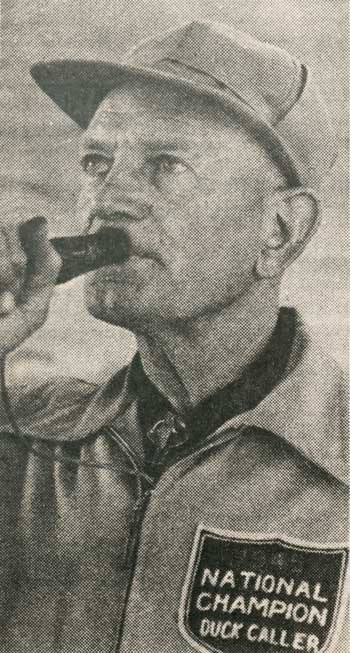

Historians agree that the late Darce Manning “Chick” Major (1896-1974), veteran duck hunter and noted call maker, is a father of modern-day duck calling. He, too, is one of several to develop the Arkansas-style duck call in the Grand Prairie region.

Major found a piece of Kentucky walnut on a business trip in the late 1930s and brought it home. Clyde Hancock of Stuttgart, Major’s friend, agreed to make a duck call from the wood. Major decided to try his hand at creating his own duck call from the same piece of walnut and whittled his first—the first of many.

His fascination for duck hunting and call making made him decide to take this venture a step further.

Major was working for St. Louis–Southwestern Delivery Service in a small truck and delivering on a route throughout the Stuttgart region. People started stopping him to talk about how he made duck calls, further increasing the demand for his calls.

“Chick did a little guiding in Arkansas and moved to Stuttgart where all the duck hunting and calling was going on,” said Pat Peacock, Chick’s stepdaughter. “We moved in a small house, and the neighbor next door had an enclosed garage. He let Chick put up his wood lathe and equipment. He made his first duck call at Mr. McCauley’s garage.”

People heard about Major’s duck calls and found where he was working. Mr. McCauley eventually complained, “All these people can’t park in front of my garage; they are blocking traffic.”

His first calls were made in the early 1940s for friends and hunters in the region. Major’s stature as a call maker improved when he won the World Duck Calling Championship in 1945, the Gulf Coast Championship, and the International Championship in 1957, causing hunters to seek out his calls.

Major started making calls to sell on Saturday, and Sundays about 1948, and the business grew. Other duck call makers asked how he was creating his calls, and Major showed them.

“Mother suggested that we find a bigger place to make duck calls,” Peacock said. “Mother was thinking how to get their three daughters through college. She was a big part of Chick’s business and taught everybody who bought a duck caller different duck sounds. She took them outside the shop and showed them a routine of necessary calling sounds for hunting or competition.”

Other family members became involved with Major’s growing business.

“We went to the shop after school to sweep the shavings and dust in the shop,” Peacock said. “We had a hose to rinse off dust before we went into the house. Our friends always asked if we knew how to make duck calls. We didn’t know but told all our friends we did. I eventually started going to shows all over the United States to promote our calls. He would not let anyone touch the reed, cork, and barrel nor do lathe work, but they put the calls together. Chick would not let a call leave the shop unless he had made it.”

Butch Richenback was a protégé of Major. He spent a lot of time at the shop, learning to blow and make duck calls, and eventually he won the world competition in 1972. He branched off to make his own line of Rich-N-Tone Calls.

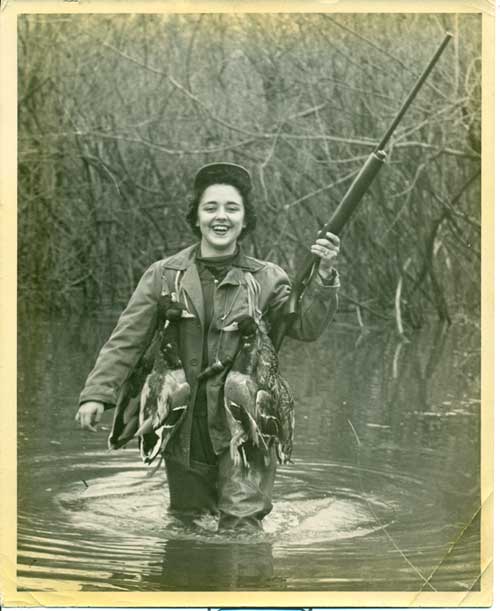

Pat Peacock Competes

“I won the Junior World Contest at age twelve,” Pat Peacock recalled. “I could no longer compete in the Junior by age 19 and won the Arkansas State Duck Calling Contest, and this started a riproar with male competitors. No one was rude to me until I won the World Duck Calling contest, and one particular gentleman was mad. The master of ceremonies was the Arkansas governor, a very serious man. He called back the top two competitors, and we both blew again. We both came back out on stage after doing our final calls, and they called him as the first runner-up. He realized that I had won and said, ‘Cheat, cheat, cheat,’ and the governor said, ‘Sir, I would like for you to get off the stage, and I don’t want you back out here. If you can come back on the stage and keep your mouth shut, then I’ll allow you to stay up here.’”

Pat was featured in a national magazine article, accompanied by a picture of her walking out of the woods that recounted how she had won duck calling contests against the men. This publicity took Chick’s business to a new level, and they strived to make enough duck calls to meet demands.

A Successful Business

Through his tenure, Major’s duck calls were used to win well over two hundred calling titles, including more than 20 by his family. His wife Sophie (1950, 1964) and both stepdaughters—Brenda Peacock Cahill (1957, 1958) and Dixie Major Holt (1965, 1969, 1971) —all won multiple women’s division World Duck Calling Championships. Pat Peacock (winner 1951–55) is the only woman in history to win the men’s division not only once but twice—in 1955 and 1956—plus the 1960 Men’s Champion of Champions competition.

Major decided to go a step further and is credited with producing the first hand-tuned acrylic call during the early 1970s.

The business, Chick Major–Don Cahill Dixie Mallard Calls, is now owned and operated by Brenda, with her husband, Don, and other family members. Fewer calls are created today, but more exotic wood is used.

The sisters are supporters of the Wings Over the Prairie Festival held annually Thanksgiving week in Stuttgart. Brenda’s cause, The Chick and Sophie Major Memorial Duck Calling Contest, has awarded more than $84,000 of scholarship funds to high school seniors in 35 schools across 13 states. Both sisters teach a children’s duck calling class originally started by Sophie during the festival.

“Chick’s original lathe, photos, and other materials are justifiably displayed in the Grand Prairie Museum in Stuttgart,” said Melody Stackhouse, Pat’s daughter. “He is a big part of this area’s history. I am proud to be his granddaughter!”