Management that Requires No Planting, Only Planning

Richard Hines | Originally published in GameKeepers: Farming for Wildlife Magazine. To subscribe, click here.

My friend Vernon Lovejoy and I had just wrapped up the Arkansas waterfowl season the previous day by shooting a limit of mallards and wood ducks in a flooded green tree reservoir. Since we were the last of our group out of our camp that weekend we had also volunteered to do the final cleanup and packing. As we were driving home that afternoon, plans were already underway for next year’s hunting schedule when Vernon said, “Good grief, where is all of this water coming from?” Several drainage ditches across the Arkansas Grand Prairie were running high and it looked as if there had been a major rain event.

Unfortunately, that was not the case since there had not been any significant rain for the past two weeks; I knew clubs were draining duck impoundments. As we drove by several of the almost bank-full canals and drainage ditches, we were talking about how everyone was heading home for the season after cleaning, storing decoys and doing one thing that may be costing them ducks in coming years. Club members were opening screw gates and pulling boards on risers draining their club’s impoundments as quickly as possible.

Annual draining of waterfowl impoundments is necessary in order to plant crops or maintain wetland production. However, draining too early will not only affect production of crops the following season, but may affect numbers of ducks in following years as well.

So how will waterfowl respond to this change? Simply put, they move on; however, hunting clubs and landowners with duck impoundments or flooded areas should take advantage of the post hunting season needs of waterfowl and in doing so, may reap rewards in future hunting seasons.

The entire focus of constructing waterfowl impoundments for most landowners is attracting waterfowl during the hunting season. Yet leaving water in impoundments through February may not only provide needed fuel for migrating ducks, but you may be helping bring more back next year by imprinting or enticing birds to stop at the site again. It is well-documented that ducks will continually return to areas with abundant food and water.

The entire focus of constructing waterfowl impoundments for most landowners is attracting waterfowl during the hunting season. Yet leaving water in impoundments through February may not only provide needed fuel for migrating ducks, but you may be helping bring more back next year by imprinting or enticing birds to stop at the site again. It is well-documented that ducks will continually return to areas with abundant food and water.

Mississippi State University Assistant Professor Dr. Brian Davis, who is currently researching spring waterfowl migration movements said; “landowners need to remember these ducks have been hunted since September and during their entire flight from Canada to the Gulf Coast, hunting season has been open. By the end of January, they finally have an opportunity to exploit enormous food resources across the region without harassment and at a time that is critical in preparing and building energy reserves for nesting.”

Most hunters don’t recognize or give much thought to the effects of draining impoundment water on the last day of hunting season, but in can be a problem for migratory birds. Generally, at that time of year, there are some large rain events so there may be ample sheet water on fields, but in most cases this is only temporary. When the end of hunting season draining occurs, almost overnight a large percentage of valuable sheet water has disappeared from the entire landscape.

All waterfowl hunters anxiously await the fall migration, but many are not aware that from January 31 to March 1 is also a critical time for birds to finish adding on proteins and fat needed for the flight north. Because of this fact, some waterfowl biologists believe that this period could be a population bottleneck by restricting numbers of breeding waterfowl.

In the 1980’s, waterfowl researcher Mickey Heitmeyer found that mallards with low body mass delayed normal courtship. What’s the deal here? Fewer pair bonds and later nesting coupled with low body reserves will have lower reproductive output than birds in good shape.

spring migration.

USGS (University of Arkansas) Wildlife Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit Leader David Krementz recently completed a comprehensive study of mallards leaving the Mississippi Delta of Arkansas during spring migration. Using satellite transmitters, Krementz and his students were able to follow 143 mallards and discovered that wetter conditions tended to slow migration causing birds to make more stops. Overall the average trip from the Arkansas Delta to the Prairie Pothole Region averaged 18 days and the 143 birds traveled an average of 1,184 kilometers or 743 miles. Most of the mallards were initiating nesting on or about April 19. Krementz’s research results also found a majority of birds wintering in Arkansas nest in South Dakota, but they also had birds nesting as far north as the Northwest Territories.

Land managers could be providing food on spring migration stopovers and the more food the better the odds are that a hen will be a successful nester. Arkansas mallards were making the most of their initial stops during the spring moving along large river corridors within large agricultural areas of Missouri. The same movement of mallards seems to run true for Tennessee as well, when large numbers of birds move out of the South and hold over along the Mississippi, Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers.

Tennessee National Wildlife Refuge Biologist Robert Wheat told me; “we hold our water in all impoundments and flooded fields until at least March 1, and in most cases if they (waterfowl) are not disturbed we will have large numbers using refuge impoundments well into the first week of March and we feel confident these birds will be in top shape when they arrive to the breeding grounds.”

The question of what you actually can do for spring migrant habitat really depends on where you are and the type of habitat you are managing. Just a few ideas for the central portion of Mississippi Flyway might include managing shrubby habitat. If your property has large sections of flooded shrubs such as swamp mallow, willow thickets or best of all a button bush area, these can be an important component of late winter and early spring waterfowl. One point though; you do not want all of your impoundments in this condition. But if you have the acres, a small section of the flooded shrub habitat will attract late season birds such as mallards.

will continue hatching and larvae are active.

As mallards are pairing, they tend to hang out by themselves with the drake working overtime to make sure no other suitors are around the hen. Typically a nice log for the pair to sit on makes shrubby habitat a favorite haunt.

Older birds and those in prime condition typically pair earlier and in turn will be the first to arrive on the breeding grounds in the Prairie Pothole Region. Well-conditioned birds year after year will produce the largest broods and with many hens and even drake mallards living many years, the payoff comes when they return to productive habitat they encountered along the flyway.

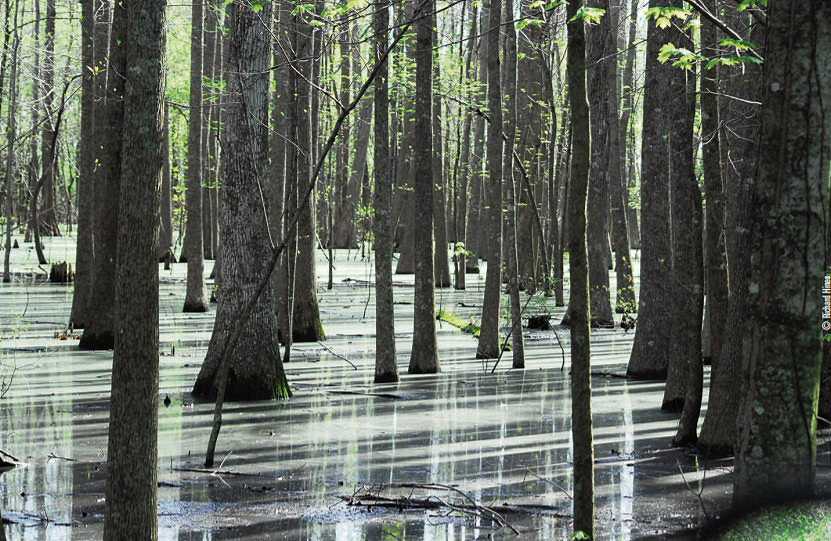

Green-tree reservoirs, or what are referred to as a GTR, are another important spring habitat. Take note as this is one habitat to pay attention to. Draining of GTRs should occur well before leaf out in order to maintain the health of the trees. As is true in the fall, GTRs with a high oak component will benefit spring migrants but by February most of the acorns in the GTR have been consumed or deteriorated.

However, no need to worry since spring is a time when waterfowl tend to increase their intake of insects. Snails abound and many insects such as dragonflies that laid their eggs on dried wetland soils or vegetation the previous summer are now hatching in the flooded leaf litter. Even when the water has a layer of ice, the eggs will continue hatching and larvae are active. Small beetles and dragonfly larvae are all at home and active in cold water and as temperatures rise into the 50-degree range the insect hatch will also increase. With all this available food in spring, waterfowl impoundments birds feeding on this site will have a smorgasbord of high protein insect larvae, many of which contain over 50- 60% protein, an essential component for reproduction.

In addition to insects, waterfowl will find seeds from plants favoring aquatic environments; barnyard grass, Pennsylvania Smartweed and many other species that are highly nutritious for waterfowl. In a nice mix like this you are basically providing the steak and potatoes for migration. Insects are the protein (steak) and many moist soil plants are providing both protein and carbohydrates.

Moist soil impoundment habitat can typically be flooded longer into the spring than other habitats. Here you are only trying to grow native plants and if you conduct annual disking, leaving water on a few more weeks will greatly enhance the seed bank for a higher quality crop of smartweed, millet, sprangletop and sedges. Another plus of delayed draining until May is the benefit to late migrators such as blue wing teal.

risers, it is best to induce a gradual reduction of water in

most impoundments, for several reasons.

Tennessee Refuge Biologist Robert Wheat also told me, “we will hold water until May 1, if we are planning to plant millet; our Japanese millet won’t go in the ground until July, which is typically dry here in Tennessee so the added moisture really helps with germination.”

If you flood crop fields each year you have to consider getting soil dried out in time to plant. A good rule of thumb is about 4-6 weeks prior to your areas corn planting date. If crop field rotations have soybeans scheduled, you could extend by a week or two. If your impoundment will be planted with millet then keep the water on longer. Also adjust water levels so they do not remain static or stationary. Overtime, stationary impoundment water levels can become less productive for waterfowl.

Management techniques vary with water control structures, but a slow drawdown is best. Don’t pull the boards on the last day of the season and head home. Instead pull only one board - depending on the size of the impoundment and time you have, I only pull a corner of the board up allowing a slow drawdown.

Screw gates are easy to open for fast draw-downs, but in the spring barely crack the bottom of the gate to let water trickle out. You may want to consider installing a depth gauge so you can closely monitor not only dropping water in spring, but flooding in the fall. The secret; you want your impoundment water level to only drop 1-2 inches per day. A rain may raise levels and if that’s the case, increase the opening to make up the difference. At this time of year you are hatching invertebrates and the slow drop will allow hatching to continue. Meanwhile you will be feeding birds as they pass through your area with management that requires no planting, only planning!

Again how fast you dewater and at what rate, depends on the depth at your pipe outlet, acreage flooded and what crop you are going to plant or manage later in the summer. There is a fine line with late season habitat management whether it is in a flooded green tree reservoir or flooded crop fields and non-agriculture waterfowl impoundments such as moist soil or millet plantings. Timing of draw-downs is a critical component of management.

Since no hunters are shooting at ducks past the end of January, most hunters expect waterfowl will make it just fine after the hunting season. This is not always the case, since some of our toughest weather occurs in February. Major winter weather events halt migration and forces birds to congregate along flyway routes. As temperatures go down, energy reserves the birds have stored also decrease. To offset this loss of energy, birds raft up on large lakes and rivers for several days at a time. These large bodies of water only provide resting sites and while this is important, they do not provide the food sources migrating dabbling ducks and geese require.

As waterfowl season comes to a close, it is not just a time for reflecting on successful early morning hunts or making plans for the next season. Post hunting season habitat can be critically important for migrating waterfowl as they make their way back to the breeding grounds. Land managers can help offset this loss of seasonal habitat by extending flooding times in waterfowl impoundments and in doing so can reap rewards in the future by enticing birds to stop and rest. It won’t happen overnight. In fact it may take several years, but as birds are imprinted to feeding, gaining energy, and resting on club impoundments, you can bet they will make stopovers during the coming fall migration.