Richard Hines | Originally published in GameKeepers: Farming for Wildlife Magazine. To subscribe, click here.

A few years ago a friend called and asked me about his idea of attracting more ducks to his farm. “All we need to do is build a levee across that little slough near Pine Creek,” he said. Drawing more mallards to his land sounded like a good idea to me, but I told him there may be a hoop or two to jump through. What he didn’t know was that you cannot dam or block a creek that is marked on a USGS map as a “blue line stream.” That’s because any work occurring in the floodplain of a stream potentially falls under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

My friend was perplexed and asked, “Even on my land?” I had to tell him yes because everything you do on or near any floodplain can potentially affect not only the wetland habitat of your land but all the land downstream from your location. You could unknowingly damage an entire ecosystem with a single levee.

Anticipating and constructing a new waterfowl impoundment always brings visions of morning skies filled with teal, ducks and geese. The actual planning prior to starting can be very frustrating, to say the least. There is more to creating a waterfowl habitat than scheduling earth-moving equipment. You have to know what permits you need and what agencies require them. Let’s look further into the process of getting a permit like the 404 permit.

The 404 Permit Is the First Step to Creating Better Waterfowl Habitat

Developing a project on a floodplain is going to require a 404 permit. The permit states this key point: Section 404 of the Clean Water Act regulates the discharge of dredged or fill material into waters of the United States, including wetlands (this includes fill for development and water resource projects such as dams and levees).

Depending on the size and location of your project, state and federal agencies have several options to provide support for landowners trying to navigate the 404 process. Many state wildlife agencies have biologists who work with landowners interested in developing wetlands — and don’t overlook organizations like Ducks Unlimited who have staff biologists. There are also private wildlife/wetland consultants who can direct the project from start to finish.

The Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) has offices in most counties across the country and can provide technical advice on building levees. In many cases, their expertise in local wetland development is invaluable. They often help landowners save the time and money associated with poorly planned wetland habitat projects. They understand the state and federal laws and regulations associated with migratory birds like ducks and geese. They also have wetland conservation resources from across the nation a phone call away.

Some landowners prefer the “do it yourself” approach to the 404 application. Landowners who go the DIY route should pay careful attention to the instructions of the 404 application. Attention to detail is a must and a well-thought-out 404 application is a big help to all those involved. Most of the regulatory staff cover large areas with heavy workloads. Having a carefully planned application makes their job easier and will help speed up the process.

Section 404 Permit Process

First, you need to determine which Corps District your project is located in because across the 21 Districts there are slight variations on permitting. To find your district, visit the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Website.

Tim Flinn, Eastern Section Chief with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, told me the first questions we ask are obvious — where is the site, how large is it, is it on a floodplain? Flinn suggested that if you have a sizable project “it may be best to hire a consultant who is versed in wetland projects” and can get through the steps. Flinn added: “There are a lot of wetland consultants out there who can furnish technical guidance for these types of projects.”

For the DIY person, I have found Corps staff helpful, but the permit process will run smoother if you review the “instructions for preparing an application.” Most questions are easy — who, when and where — but pay close attention to questions on “Nature of Activity.” Here you need to describe where the building material (soil) is coming from and going to, as well as the size (height and length) of the levee. The permit also requires drawings. The good news is you can hand draw one on paper. Just make it clear and precise. Again, there are examples on the website.

Determine the Total Cubic Yards of the Levee

Once you know the size of the levee, there are conversion charts on the internet that help you calculate cubic yards. You will have to provide the total cubic yards of material you plan to move. “Total cubic yards” is an important number, but it does not need to be exact. The estimate immediately helps engineers determine the magnitude of the project. Just remember that as the levee height increases, so does the complexity of the project.

Provide a Map

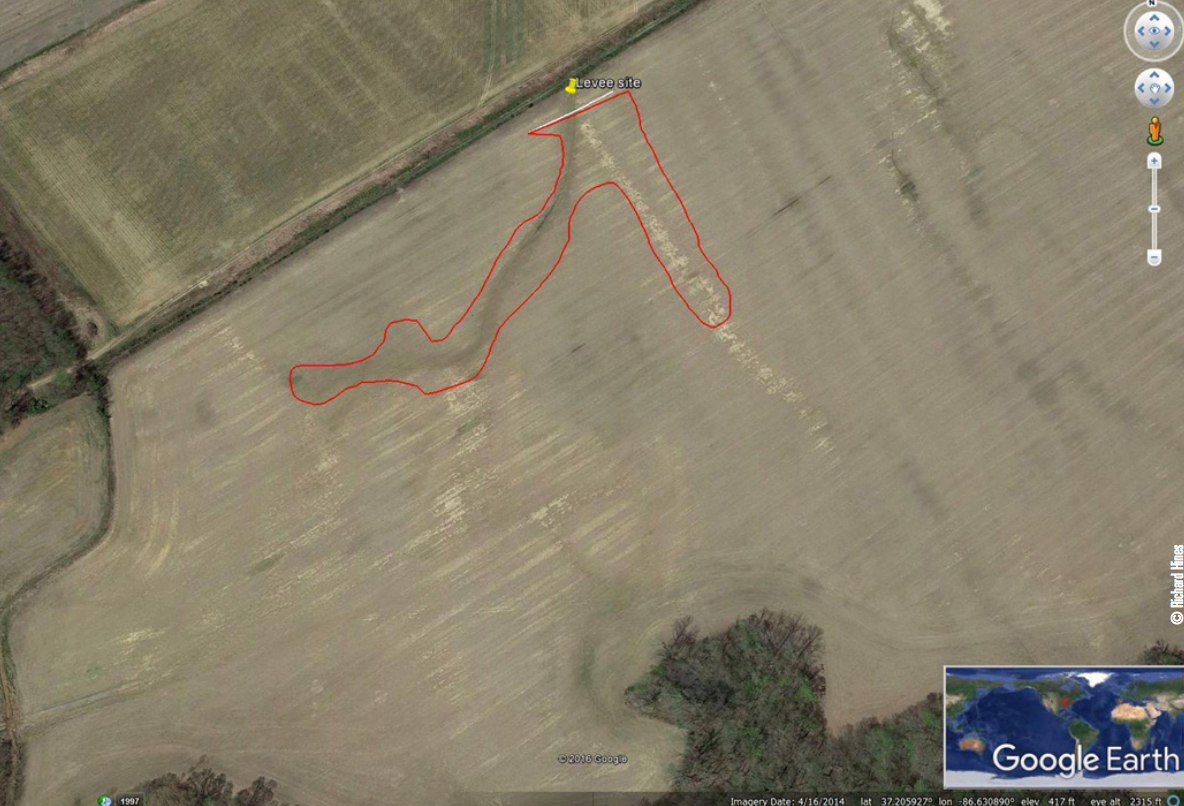

The application needs a map and Google Earth works perfectly. The toolbar setting allows you to sketch the outline of the impoundment, levee location and where soil will be taken from. A second map should be on a smaller scale showing the site in relation to nearby towns and other features. Attach your hand drawing here and make sure you are showing the levee design including height, slope, length and location of the water control structure.

Section 404 Permit Requirements

Very often, mitigation or replacing lost habitat is required due to the project changing elevations on the floodplain. Obviously, adding fill at the levee changes the elevation. It has been found that an elevation change of only one foot in a floodplain could alter plant composition and habitat.

If mitigation is required, landowners may be able to mitigate the project on their land. An example of mitigation would be replanting trees on a portion of bottomland where a forest was cleared for farming. Restoring this small amount of farm ground not only offsets the disturbance but provides habitat for waterfowl, deer and turkey. If you do not want to mitigate on your land, there are “Mitigation Banks” where you pay someone to restore land at another location. Again, before you start in this direction, you must have an approved mitigation plan describing how you will restore and replant the site. For mitigation projects, it is highly recommended that you hire a consultant to walk you through this process.

I asked Flinn a common question I often hear: “Why mitigate a wetland when you are constructing a wetland?” Flinn told me the Corps understands that you are putting in a wetland. However, it will only be wet for a few months each year. Because of its temporary nature, additional measures are needed so there is not a total loss of wetlands. Back in the 1990s, President Bush signed an order so from that point on there would be a “no net loss of wetlands.” Mitigation is the tool that assures our remaining acres are retained.

Another situation you may encounter is that the Corps requires that more acres be mitigated than are being altered. If landowners construct levees in a forested habitat where older trees are removed, the additional acres of young trees offset the loss of mature trees. This mitigation is generally for the area where permanent fill (levee) is placed in a wetland.

The Corps may also add stipulations to your permit. For instance, when constructing a Green Tree Reservoir (GTR), you might be required to break the impoundment up into three separate units. Each year, one unit remains dry. These types of rotations are a normal management practice for GTRs. Research has shown that woodlands that are flooding continuously each winter are not as healthy as those with occasional dry periods through winter months.

Using a District Conservationist

If all of this sounds rather difficult, remember you are only a few minutes away from your local Natural Resources Conservation Service office. At each office, you will find a District Conservationist or DC who can walk you through the process. Chase Coakley, the NRCS Area Resource Biologist in Tennessee, told me that practices and assistance are available to everyone, but programs and assistance do vary per locality.

Each DC has their own line of expertise, but if they are not familiar with designing wetland projects, they have access to other NRCS professionals including engineers, soil scientists and biologists who can help complete a project design.

Using the NRCS Office

When you visit an NRCS office, the DC will review objectives and location maps, as well as soil capabilities and watershed information. At this point, they will advise you about the technical assistance NRCS can provide and even if cost-share assistance is available. Coakley told me that “there are sometimes separate pools of money that help underwrite projects, but this varies from state to state and year to year.”

After the office visit, the DC will make a site visit before making any decisions on the final project. If the DC feels that additional expertise is needed, they will schedule an NRCS engineer or biologist to help determine if the project will be a viable wetland for waterfowl.

Next is the permitting process and here is the big plus for going to the NRCS. If cost-share assistance is being used, NRCS will take the lead on the 404-permitting process. Coakley added, “If it is only technical assistance such as providing a design or management information, we can still offer that service of helping landowners go through the permitting process.”

Although the NRCS is a non-regulatory agency and everything you do with them is on a volunteer basis, you still need to be aware of compliance issues. If you are farming and receive USDA benefits, you must comply with the rules. For instance, if you decided to clear a woodland to construct a wetland that would potentially have a commodity crop planted on it, you need to have NRCS evaluate the site. Additionally, if you are going to construct your impoundment on existing pasture or cropland, you should get approval on current wetland provisions.

If you are a new landowner or have never worked with the NRCS before, Coakley suggested going to the Farm Service Agency (FSA) to get farm records established. FSA will check your eligibility and create a farm record.

Additionally, if you construct the levee with government funds, there may be some guidelines you need to follow. An example might be planting only a portion of the impoundment in crops such as corn or milo each year. The remaining portion would be moist soil or native wetland plants such as millet. Again, these recommendations will vary from region to region. Other management guidelines could specify the timing of drawdown to assure the impoundment has water at critical times, such as spring migration periods.

The Application Is Worth the Ducks

Why all the fuss? Consider that many states have lost over 95 percent of their original wetlands. Because of this, President Bush signed the order for a no net loss of wetlands. Every remaining acre is important to waterfowl and the other wildlife species we all enjoy. These regulations assure we will maintain this habitat for years to come.

Working on 404 applications takes time and you will find it is easier to start right than to have to back up and start over! Allow time to obtain the permit — and with proper planning and design, you will see those flights of ducks when first light begins to brighten the morning sky!

Once your pond is built, you'll want to make sure incoming waterfowl have everything they need to feel comfortable, safe and fed. What starts as a pond to draw mallards, often creates an ecosystem that benefits all wildlife. To learn more about keeping ducks on your property and creating the best Duck Accommodations possible, click here!