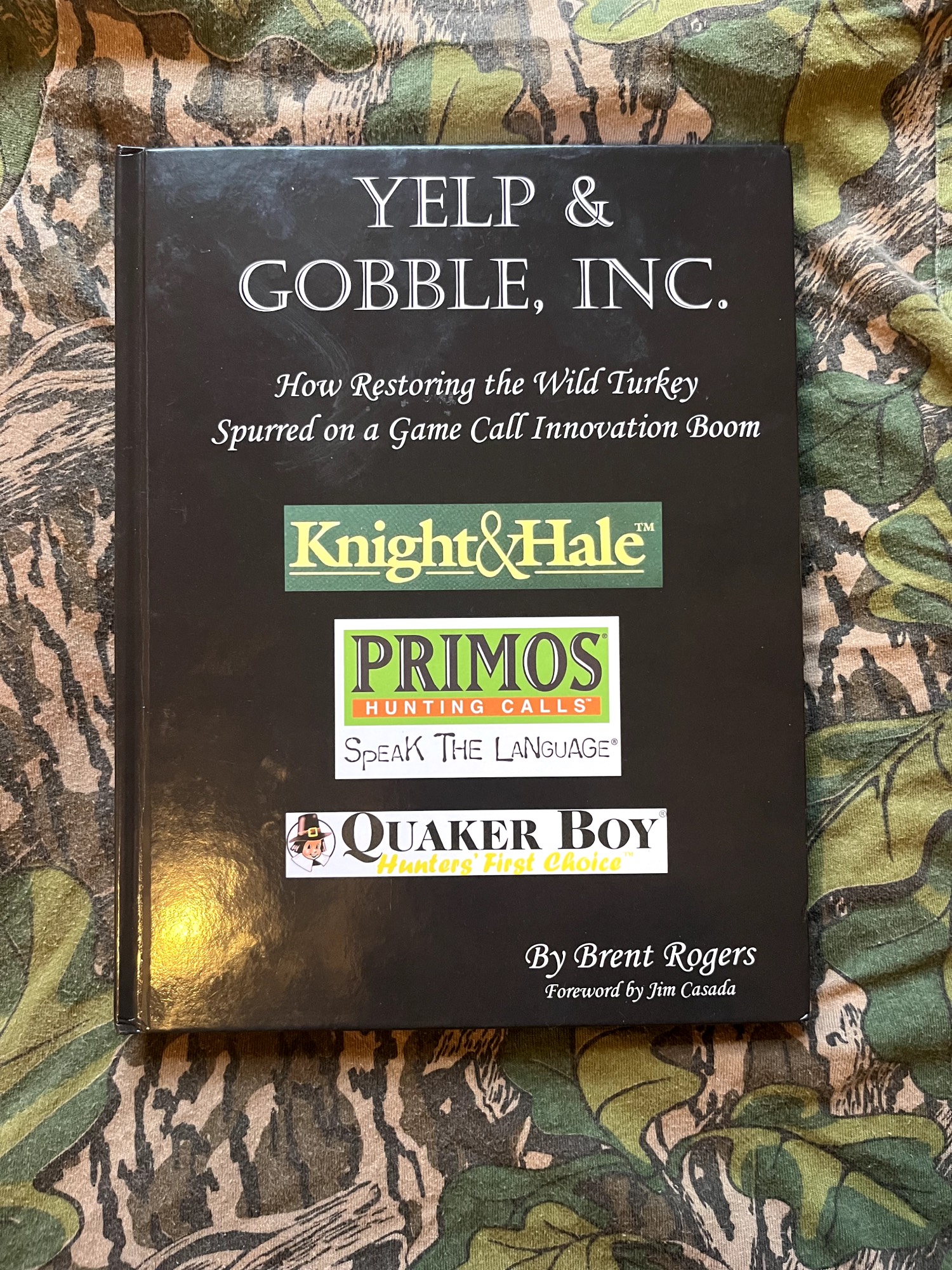

The below is the preface of Mossy Oak friend Brent Roger's book, "Yelp & Gobble Inc." We believe the preface does an incredible job at explaining both what the book is and why its important to the past and present of turkey hunting and all those who love the wild turkey.

You can buy a copy of "Yelp & Gobble Inc." here; we encourage you to get your copy and understand a key part of the turkey hunting industry boom.

Preface to Yelp & Gobble Inc. by Brent Rogers

"I am the last of my race, my name ends with me."

This was the justified lament in a local newspaper when the extinction of the heath hen was officially recognized. Once bountiful across New England, overhunting and habitat loss shouldered them out. A subspecies of the greater prairie chicken, it had been a dependable source of food for generations of Native Americans and the Pilgrims. By 1870, it was extinct on the mainland, and with the final few on Martha's Vineyard eliminated in 1933, its booming was eternally silenced.

This was not something new but a troubling pattern. In 1852, the great auk, found along the coast of upper North America, was reduced to a memory, as was New England's Labrador duck by 1878. In 1914, the last known passenger pigeon, with none to return its soft calls, took the final breath of an entire species. In 1918, the last colorful Carolina parakeets would follow that course to extinction. More recently, it is feared that "The Lord God Bird," the Ivory-billed woodpecker of the southeast, is likely extinct due to the loss of old-growth forests.

Don't be alarmed; I am not here to harangue you with gloom and doom. However, it is important to establish that this book came close to never being written. The American wild turkey was on the same. path to extinction; thankfully, it is a survivor. We are just a century removed from grim days when it looked like our proud, native bird was a goner. Early explorers, settlers, and naturalists, up to then early 1800s, enthusiastically reported large concentrations of wild turkeys. Naturalist William Bartram reported in the late 1770s, "The high forests ring with the noise...of these social sentinels, the watch-word being caught and repeated, from one to another, for hundreds of miles around; insomuch that the whole country, is for an hour or more, in a universal shout." Even today one can only imagine a chain of gobbles for hundreds of miles. How fortunes can change! In the 1830s, just half a century after Bartram penned those words, the now-renowned John James Audubon noted a decline in the number of wild turkeys. He wrote that they were "less plentiful in Georgia and the Carolinas" and were "becoming less numbers in every portion of the United States." The wild turkey population plummeted from an estimated ten million when Europeans first set foot in North America to less than 200,000 by 1920. The wild turkey, too, seemed to be on the brink of extinction.

It was not a simple thing to save a species. It required sacrifice, effort, and an investment of time and resources from many. Those endeavors came in the passage and enforcement of laws, closed seasons, reduced bag limits, resolute landowners, and disciplined hunters. It required these different stakeholders to band together to form conservation organizations. Still, lessons had to be learned using new game management practices and utilizing new technologies before they got it right. Technology adapted from World War II included the development of cannon nets (then rocket nets) to fire over turkeys, allowing their safe and effective capture and transport. It also included radio telemetry, which was a critical tool for biologists to monitor the success of transferred turkeys.

As a united force, they overcame the myth of the game farm turkey, muted the p poachers gun, and championed better land management practices. By the 1970s and the 1980s, they established a new nationwide generation; those born after the 1980s won't likely recall a time without wild turkeys in their state.

It took five decades of law, learning, and effort to restore the population to one million turkeys by the 1970s, and by the year 2000, the population exceeded five million birds. To put that in context, there are now eight individual states whose wild turkey populations each exceed the total number in existence just seventy years earlier. Significantly, the conservation efforts on behalf of the wild turkey have also benefitted many other game and non-game species. It turns out that what is suitable for the wild turkey is good for its neighbors.

This post-restoration era has seen all fifty states, except Alaska, enjoy new revenues from the sale of turkey hunting licenses, tags, and stamps, funding more conservation work. The federal Pittman-Robertson Act uses money collected from hunting license sales and taxes on firearms and ammunition to restore, manage, and enhance wild birds and mammals and their habitat. Most who criticize hunters do so without realizing the wildlife and natural areas they enjoy are often tied directly to dollars coming from hunters. The National Shooting Sports Foundation reported in 2018 that "Hunter spending generates more than $185 million per day for the US economy." The wild turkey is a wildlife success story that was enabled by and through hunters.

Out of that success story, the foundation was laid for the subject matter of this book. Despite a close call on the ability to have and hunt wild turkeys, we have been blessed with a privilege that required our diligence to avoid past mistakes. Now, I must qualify the scope of this book.

I revere the American wild turkey (that should now be obvious!) and the American bison. Those two members of our North American fauna are symbolic of the spirit of freedom and wildness associated with the history of the United States. Given enough time, anyone who has engaged in a conversation with me knows that I can turn any discussion to wild turkeys. So much of my passion revolves around the wild turkey that much of my leisure time is spent in pursuit of knowledge and collectibles associated with them.

The American wild turkey is worthy of praise. There are mutterings of well-meaning but misled farmers who see turkeys in their fields during the daytime eating bugs, weed seeds, and waste grain and blame them for crop damage. In reality, squirrels, nocturnal raccoons, and deer do most of that damage. Understandably frustrated are urban dwellers living in close quarters with turkeys taking advantage of backyard feeders and the lack of predators. The truth is that the wild turkey is marvelous at eking out a living in a world where everything that breathes seems to want to eat it.

The wild turkey earns respect from those who take the time to study it. They are a pleasure to observe, with their sleekness of form, the stealth of their movements, and the shimmering robes of iridescent plumage they wear. It has proven its mettle and adaptability by living in swamps, rainforests, deserts, mountains, and just about any habitat found between the Pacific and Atlantic oceans that contains some trees and fresh water. Also, like Homo sapiens, they are omnivores and social creatures wise depths of spirit were captured firsthand by ethologist (a scientist who studies animal behavior) Joe Hutto in his eye-opening book, Illumination in the Flatwoods. PBS Nature would later produce the documentary "My Life as a Turkey" based on Hutto's experiences over two years with his imprinted wild turkey brood.

In greatest admiration of the turkey are those whom one might least expect: the hunter. I place myself in that class. There are slobs among us, those who exploit such wildlife or whose interest in confined to reveling in that basest part of the process, the kill. The honorable hunter loves the turkey's life more than its death. We live closer to it than others and come to know its vulnerabilities and its seemingly supernatural abilities. Its brain is a pitiful size compared to ours, yet it humbles us in ways only hunters fully comprehend. Its death gives us life, and our triumph comes with a twinge of regret. Those heartfelt feelings keep good hunters honest, and we are bettered by knowing the actual cost of the sustenance on our tables.

While this story will celebrate the origins and innovations of some production turkey call companies, the real story I will tell here is about people. People run businesses. People design, make, and produce turkey calls and other outdoor products. People purchase those products and hunt turkeys. Although I provide a fair amount of data and information that will help establish some historical records and serve as a guide for collectors, this is a human interest and business innovation story.

In the following pages, I will cover the journey of a few successful companies started by people who were uniquely placed in time to accomplish what they did. These individuals fit Malcom Gladwell's definition of Outliers in his book of the same name. Many enterprises to make turkey calls and products for the masses were launched, but few persevered and succeeded over decades.

In early 2023, I co-authored a book with George Denka, the Turkey Call and Literature Collector's Guide. It is a continuation of the late turkey call enthusiast Earl Mickel's books that provide short biographies on turkey call makers and a perspective on the collectability of value of their calls. This was George's fourth edition since being handed the reins by Mickel. I have become obsessed with collecting the tangible items of turkey hunting: books, magazines, calls, audio, video, clothing, stamps, art, and anything turkey hunting-related I can find. In George's book, my contribution was primarily on wild turkey literature; here, I delve more into the history of "factory" calls and products.

As much as I love the "stuff," such items will eventually lose meaning if the stories behind them aren't captured for posterity. We have mostly lost the generation that lived in the "lean years" when wild turkeys were scarce in this country. As the wild turkey flourished again, a new generation of turkey hunters rose to re-forge this great tradition. I consider that the greatest generation of turkey hunters, which we are now starting to lose. Fore those who will never get to meet them, their passion and personalities are preserved for us through their calls, recorded voices, and images. This book is an effort to capture for posterity their accomplishments and impact. They made kids like me dream and then were part of making my dreams come true.