provided by John Phillips

Dr. James Earl Kennamer is the retired chief conservation officer of the National Wild Turkey Federation (NWTF) in Edgefield, South Carolina. He’s spent 60 years hunting and researching the wild turkey. He received a B.S. in wildlife management from Auburn University and a master’s degree and a doctorate from Mississippi State University.

Editor: What’s the future of wild turkeys and turkey hunting, in your opinion?

Dr. Kennamer: At this point, we’ve pretty well defined the problem, however, so far we’ve only talked about turkeys in the South and the Southeast. But turkey biologists have learned that these problems are pretty much universal. We’re seeing the same problems with turkey flocks all across the nation. If you look at all the prime habitat that turkeys have lost each year, you realize that turkeys have fewer places where they can exist. If we continue to lose turkey habitat at the current rate, we’ll have to continue to put measures in place to reduce the number of turkeys each hunter can take during the season and possibly reduce the length of the seasons to help slow the decline of turkey flocks - at least to some degree.

Editor: We’ve seen deer habitat decline nationwide. In many areas of the country, we’ve seen large numbers of deer move into suburban areas and highly populated places where there's just fingers of woods and cover where whitetails live. Will the turkeys, at some time, adapt to smaller habitats in suburban areas like the deer have?

Dr. Kennamer: Yes. We are already seeing that type of migration right now - typically in New England where many sportsmen don’t hunt turkeys, and in gated communities where there are instances of turkeys in residents’ yards. Any place where the wild turkey is protected and doesn’t hear a shotgun, he’ll move into those areas and thrive - be in your front yards, jump up on your picnic tables, and run on your patios - much like the problems we’ve experienced with the increased number of Canada geese nationwide. Where the geese have been hunted, that problem seems to have stopped.

I helped, through the efforts of the National Wild Turkey Federation, to reintroduce turkeys on Long Island where the area had its first season for hunting wild turkeys in 200 years. Now people there are being attacked by turkeys in their yards. These turkeys have no fear when they haven’t been shot at before. I believe the turkeys start thinking they are humans, since they’re living right where humans do, and no one is running them off. However, when the hunters move in, and the guns come out, the turkeys get a clear understanding of where they’re supposed to be to stay relatively safe, and where they can’t be without possibly becoming a turkey dinner.

Editor: Would it be too radical to believe that one day we may be trapping turkeys in suburbia and transplanting them to woodlands outside of suburbia?

Dr. Kennamer: Catching and transporting turkeys is currently being done in some places where the turkeys are creating the kind of problems I’ve mentioned: attacking people and running across yards and patios. That type of trapping and transplanting turkey is being carried out in some New England states today, as well as in gated communities where the turkey is protected.

Editor: Do you think the program of transporting populations of turkeys from suburbia into wild places may happen in the South and other regions of the nation?

Dr. Kennamer: I can’t look into a crystal ball and say that for sure, but as there are fewer and fewer places where people are allowed to have guns and to hunt, those turkeys will move into those regions and start repopulating. So, sooner or later, something will have to be done to get those turkeys out of the neighborhoods.

Editor: Turkeys haven’t become nuisances in some areas like the Canada geese have - living in golf-course communities, parks, picnic areas and gated communities as well as states that don’t permit residents to hunt.

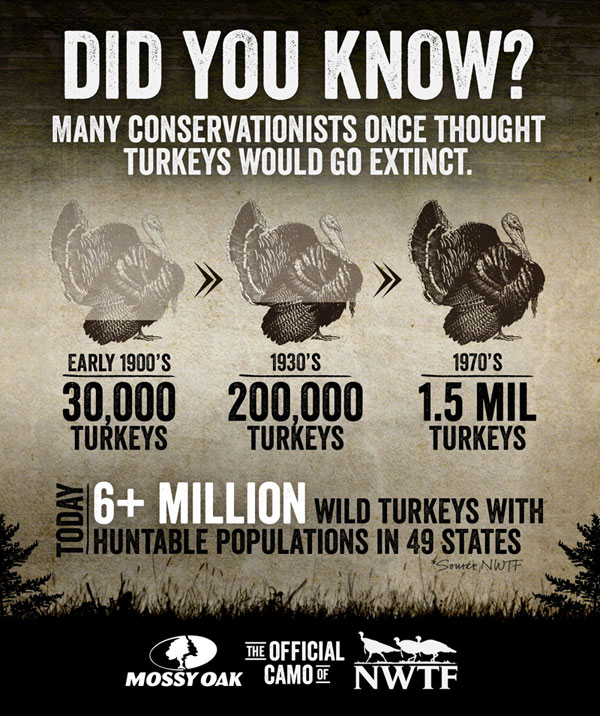

Dr. Kennamer: I don’t think the wild turkey will come back in as large a number as the Canada geese have, but as far as being nuisances, they certainly have the potential to be seen as nuisances. What’s ironic is that through conservation efforts of the NWTF and state conservation agencies, we’ve been able to bring back the wild turkey, the greatest game bird in the world. And now some communities look at turkeys as being vermin or trash. It’s like some people look at Canada geese, call them sky carp, a rough fish with no redeemable qualities. We’ve done a good job as sportsmen to bring the wild turkey back in almost every state. I hope we can continue to hunt the wild turkey in the future, and bring those birds back to where they can maintain themselves and continue to be a reliable source for food and sport well into the future.