Bob Humphrey

Lines on a Map

Ask most any experienced turkey hunter and they can quickly rattle off the names of the four subspecies or races of wild turkey recognized by The National Wild Turkey Federation for purposes of their Grand Slam. A fair number could probably add a fifth for the North American Slam and a sixth for the World Slam. For those not already familiar with them, they are as follows:

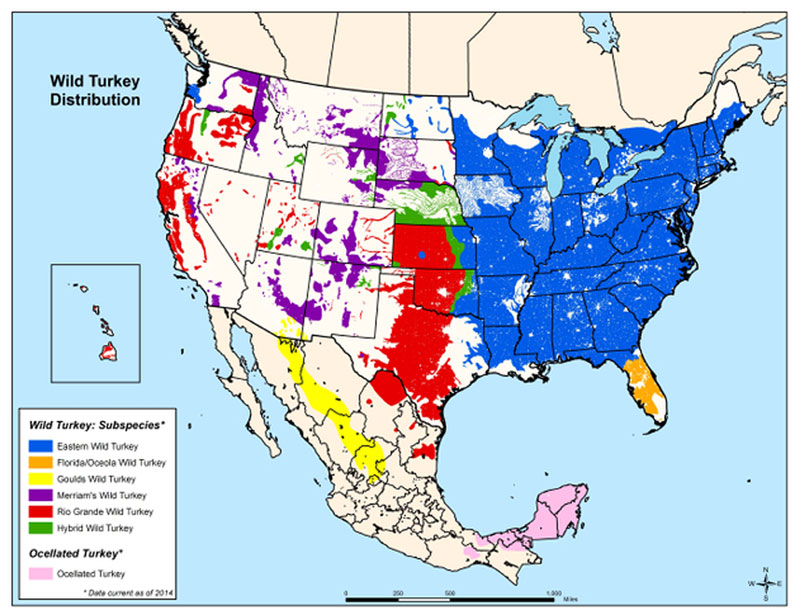

Eastern - The Eastern is the largest and most wide-spread race, occurring in every state east of the Mississippi River and along the length of the river’s western side, as well as eastern portions of several plains states and Texas. They are the largest (heaviest) race, sport the longest beards and are best distinguished by chestnut brown tips of their tail feathers and tail coverts. They’re strong, deep-throated gobbles are symbolic of the wild turkey.

Osceola - The Osceola (or Florida) turkey has the narrowest range, occurring only in central and south Florida. They closely resemble Easterns except they tend to be leaner with longer legs, and their primary wing feathers have heavy black barring, as opposed to Eastern where the black-white barring is more even. Their gobble is essentially indistinguishable from an Eastern.

Rio Grande - The Rio Grande’s range spans roughly from Kansas, south through Texas and into Northeastern Mexico, with transplanted populations in California and Oregon (and Hawaii). They are best distinguished by the tan tips of their tail feathers and tail coverts. Their gobble is noticeably different from that of Eastern and Osceola, being more high-pitched and warbly.

Merriam’s - The Merriam’s is scattered across parts of Arizona, New Mexico, up through the mountain states into Nebraska, the Dakotas, and along the Washington, Oregon and Idaho borders. It is best distinguished by the light buff to white tail band and coverts, and showing more white than dark banding in the primaries. While similar to the Rio, its gobble is even higher pitched and softer.

Those are the general guidelines, but for every rule there are exceptions. A century ago, much of what is now their current range was unoccupied by wild turkeys. Thanks to the efforts of state wildlife agencies and NWTF volunteers, turkeys have been restored to most of their historical range through trap and transfer programs. But the folks conducting those efforts weren’t too particular about where their birds came from, as long as they were wild birds. As a result, current subspecies distribution is not nearly as distinct as it once was.

In general, the variance is local or regional. For example, Massachusetts’ turkeys came from New York, and Maine’s came from Vermont and Connecticut, but variability is all over the map.

Alabama provides an interesting example. In areas that were repopulated with transplants, the turkeys resemble those in neighboring states. But in areas where the native stock was never extirpated, turkeys look more like Osceola turkeys, with slim bodies and long legs. Some think these birds and Osceolas are representative of a true southeastern strain. Then there are more glaring exceptions. The most extreme is probably Washington, where you can find Eastern, Rio Grande and Merriam’s.

While man played the predominant hand, some of the racial integration was and still is done by the birds themselves, mostly where the geographical range of subspecies overlap. There, you’ll find a lot of hybridization. In east-central Kansas, for example, you may find birds that gobble like Easterns but look more like Rios, and vice versa. And they tend to be among the largest. Nebraska and South Dakota have hybridization of Eastern and Merriam’s.

Occasionally there’s just no explanation for what you observe. I hunted a ranch south of San Antonio where we shot birds that had that silly little girl, laughing gobble of a Rio Grande, but looked like Easterns, with brown tail bands and coverts. And on a single hunt in western Nebraska I killed three birds, one resembling an Eastern, one a Rio and the third looked pure Merriam’s.

Because translocation and hybridization have led to so much diverse integration, taxonomists tend to ignore subspecies or races and simply lump them all under one species. The lines on a map distinguishing subspecies range are largely just that, lines on a map. However, they do serve as geographic boundaries for purposes of recording your Grand Slam. To my knowledge, Texas is the only state has separate regulations for different subspecies (but I could be wrong about that.)

IF YOU LOVE WILDLIFE AND WANT TO IMPROVE HABITAT SUBSCRIBE TODAY!

Management

Back when I was a budding wildlife student, my professors would tell us that much of wildlife management is people management, and that’s especially true when it comes to wild turkeys. For the most part, the birds do quite well if left to fend for themselves. At the state level, most management programs simply involve regulating hunter harvest to ensure the resource remains healthy and renewable. However, there’s a lot that can be done at the local level to produce and maintain healthier populations.

When it comes to turkey habitat, the good news is, most of what you do to manage or improve the deer habitat on your ground also benefits turkeys. Both are considered edge species, preferring the ecotone, or interface between habitat types - so, in general, the more edge and diversity, the better the habitat. Beyond that, there are some more specific steps you can take.

However, it’s difficult to get too specific with turkey habitat management recommendations because conditions vary so much across the species’ range, and because they’re such an adaptable species. In general, you want to maximize the general habitat variables: food, cover, water and space. Then look for the lowest hole in the bucket - which element is in least abundance - and patch it. And as with deer, you want to make sure your habitat meets the turkey’s changing needs throughout all four seasons.

Year-Round

Let’s start with their year-round needs, and at the top of the list is “roost trees.” Turkeys need a place to sleep at night. In my part of the world, it’s usually a big white pine. If the birds can find one, they’ll shun all other suitable trees. Height provides protection from terrestrial predators, and thick evergreen branches offer protection from owls and the elements.

In the south it might be a giant oak or other hardwood, which are usually in good supply in bottom lands and stream protection zones. Out west, it’s likely to be a cottonwood, which you’ll also find near stream bottoms and shelter belts. But as mentioned, turkeys make do with what they have, and I’ve seen birds in Texas roost on power poles, shooting houses and 10 foot tall mesquite bushes. Bottom line - try to keep sufficient roost trees on the property, the more and the bigger, the better, at least when it comes to turkeys.

Spring

Spring means green-up, an increasing abundance of herbaceous greens. The birds can usually find enough to eat on their own, but give them more in the form of food plots and they’ll be better off for it, now and later on. Again, your deer plots will do just fine, but if you want to plant specifically for turkeys it’s hard to beat clover and chufa. The former you can plant almost anywhere while the latter requires loose, sandy soils.

Gobblers need strutting areas. A tom will strut most anywhere when he’s in the mood but he’d much rather be in the open, where the ladies can see him, and he can see predators. That could be food plots, or just logging roads and two-tracks, all things in fairly good supply on most managed properties.

More important is spring nesting cover. Somewhat like a strutting tom, a hen will nest where she has to, but she’d much prefer some dense cover. That might be as complex as those same hinge-cuts you made for deer bedding areas, or as simple as a slash pile left over from your winter firewood cut. They will also nest in CRP areas and densely vegetated fields, so adjust your mowing schedule accordingly.

Far more important for productivity and poult recruitment is predator control, and you don’t need me to tell you how to do that. First, I’m no expert. Second, it would take another entire article, and then some. If you know what you’re doing, do it. If not, consider hiring a professional who does. Chances are it will also help with your fawn production, especially if you have coyotes.

BECOMING A GAMEKEEPER IS NOT JUST THE BEST WAY TO PRODUCE GREAT HUNTING… IT’S THE BEST LIFE! SUBSCRIBE TODAY.

Summer

At the risk of sounding like a tourism brochure, summer is the time of plenty, when nature abounds with life. Absent of some environmental catastrophe, there’s plenty of food. But the easier it is for turkeys to find the right food, the better. Right now, rapidly growing poults need protein, in the form of insects and invertebrates. They’ll find some in the forest but an open field or food plot full of hoppers and crickets is like an “all you can eat salad bar” for them. Even the skid roads and two tracks the toms used for strut zones will have more insects for their growing offspring.

Summer can also be the driest period. For the most part, turkeys will get the moisture they need from their food, as evidenced by their abundance in even the most arid regions. Add water, where it’s scarce, and it only makes finding food easier. And the turkeys will come simply to drink - that’s why lying in ambush near a tank is a popular tactic in Texas.

Fall

The key for fall is food, and we’ll lump late summer in here as well. As summer draws to a close, herbaceous plants are maturing. It can be somewhat stressful for deer as the greenery begins losing its nutritional value, but it’s a boom for birds because maturing forbs and grasses produce seeds. Meanwhile, vines and shrubs are also producing a smorgasbord of soft mast like grapes and berries. Many species grow wild, particularly in disturbed areas like cut-overs, and along those well exposed habitat edges mentioned above. But mast production and availability from wild plants can be variable and unreliable. If you’ll pardon the pun, you can hedge your habitat bets by planting groves or patches of soft mast producing shrubs and trees.

Speaking of trees, many of the same species you plant in your mast orchards for deer will also benefit turkeys, particularly after the soft mast crop passes. As that group of plants dies or goes dormant, the turkeys now turn their attention to what’s left: nuts and that remains the case through winter, when food and cover are most scarce, and when turkeys can sometimes make themselves quite unwelcome.

In the west, they may tear into hay bales meant for livestock. In the northeast they’ll do the same to the plastic sheeting covering silage piles. The birds will make the most of whatever they have and somehow they find a way to withstand winter. They’ll scratch away the frozen leaves to find acorns overlooked or possibly even stowed away by small mammals. They’ll plow and paw through deep powder to eat frozen clover. If the snow freezes to a crust they’ll walk on top and feed on the windblown catkins and seeds of birch and ash.

If you provide enough food on your ground, you stand a better chance of keeping the turkeys home and healthy, and keeping your neighbors happy. It’s always preferable to provide natural food but if you’re going to provide supplemental feed this is the time to do it. Just be conscientious and careful how you go about it because like deer, turkeys can quickly become dependent on you for survival when fed supplementally.

Summary

All things considered, turkeys are much easier to manage than deer. Make sure they have a sufficient amount of the proper habitat variables, which is typically the case on most managed and many unmanaged properties. Keep the predators down, time your mowing and burning to avoid nesting periods and manage your harvest rates to avoid over-exploitation. The turkeys will take care of the rest themselves. They even do a pretty good job of limiting harvest by outwitting us more often than not.

Bob Humphrey is a wildlife biologist who participated in the first modern turkey hunt in Massachusetts in 1980. Later he assisted with turkey translocation efforts in Maine and in 2006 became the first per-son to officially record a wild turkey Grand Slam with a crossbow.