Bob Humphrey | Originally published in GameKeepers: Farming for Wildlife Magazine. To subscribe, click here.

need nesting habitat, reliable water, brood rearing cover,

grit sources, shelter and roost trees.

I recall a field trip I once took as an undergraduate wildlife student — it was mid-winter, and we were loaded onto buses that took us to a remote area that was normally off limits to the public. It was also one of the only areas in the state that offered a chance of spying two relatively rare species.

Our first stop was at a high point overlooking a frozen reservoir. Biologists had placed several roadkill deer on the ice in hopes of luring our primary objective. We piled out of the bus, unlimbered our binoculars and scopes, and before long someone spied it — a bald eagle soaring in the distance. At the time, this species was on the brink of coming back, and for some of those present, it was their first ever sighting.

After the initial thrill subsided, I began scanning the frozen woodlands for our other objective. It took a considerably longer time before I finally picked up several large black shapes moving through the trees. A quick switch to the spotting scope confirmed that they were indeed wild turkeys. It would be several more years before these birds and others transplanted around the state became numerous enough to allow the first hunting season in over a century.

The restoration of wild turkey populations across the continent is truly one of conservation’s greatest success stories. Although many people love watching these creatures interact in the wild, the primary motivation for most folks is having the opportunity to hunt them. In order to hunt turkey, they’re obviously have to be enough birds on a property to hunt. When feeding and maintaining these birds, if you provide them with an abundance of nutritious food, the turkeys are more likely to grow, multiply and hold on the property. In order to provide these creatures with the right nutrition, you have to know what turkeys eat throughout the year.

Summer

While looking out on the back forty, I spied several dark shapes moving through the tall grass, necks held high like periscopes navigating a sea of vegetation. A quick look through binoculars revealed three hen turkeys. That quickly piqued my curiosity as I suspected they wouldn’t be alone.

It took a considerable amount of glassing before I spotted what I was looking for. First one, then another and then one more diminutive dark shape stepped into the mowed glade along the field edge. These tiny fuzz-balls with legs couldn’t have been more than a week old —the mating season had thus far been successful.

We start our dietary calendar in the summer, partly because this marks the beginning of a young turkey’s life.

Wild turkeys are “precocial,” which means within a short time of hatching, they’re on their feet, eyes wide open and able to feed themselves. They just need a little help from the mother hen in determining what exactly to eat.

While their diet includes a wide variety (which we’ll cover in more detail as we go), the principle need for growing chicks is protein. They can get some protein from plants, but the most readily available source is insects (and other multi-legged invertebrates). Studies show that insects make up as much as 80 percent of a poult’s diet during the first week after hatching but declines steadily thereafter, with beetles and grasshoppers being among their favorites.

Research also shows this important protein source is most abundant in open areas like fields, food plots, along roadsides and in grassy rows of young plantations. Chicks can still find insects in older stands, but it can be more difficult. In forested areas, their diet consists of more plant matter, often grass, rush and sedge seeds and soft mast. They can still find enough to eat, but the more open “bugging” areas a land manager can provide, the better the growth, survival and productivity rates they will experience.

Late summer is a time of bounty. As grasses, sedges and forbs cease growing, they go to seed. Meanwhile, soft mast can be found ripening on the vine and the stem. By late summer, the juvenile birds’ diet is nearly reversed, with plant matter often making up 75-80 percent. They eat what they can find with crop and weed seeds and soft mast such as blackberries among their top favorites.

Here again, fields and food plots are important. Young cutovers and burned areas can also provide a bumper crop of soft mast like blackberries and raspberries, not to mention insects.

Fall

It was a balmy, early fall afternoon. I’d barely settled into my treestand among the oaks and wasn’t expecting much action for several hours when I heard a commotion in the distance. “Much too early, and too loud for deer,” I thought, but I picked my bow off its hanger and stood, just in case. The sound of rustling leaves got closer and louder, yet I was still unable to determine the source for several very long minutes. I was becoming increasingly anxious when I finally picked them out — these creatures weren’t my primary target, but with a fall turkey tag in my pocket and the season open, I shifted my objectives quickly. When most of the flock was obscured by brush, I seized the opportunity to draw and send an arrow on its way. Thanksgiving came early that year.

With the greens dried up and weed seeds diminishing, turkeys now turn their attention to what is readily available. They also sense that winter’s coming, and their walnut-sized brains tell them it’s time to fatten up. For turkeys, and as for deer as well, the best natural source of fat and carbohydrates is hard mast.

In agricultural areas, waste grain or unharvested crops take on added importance, as do food plot crops on managed lands. It’s important to note, however, that turkeys find much of their diet in forested areas. They also need shelter and roost trees, which is why it’s important to maintain a certain percentage of this habitat type on your land. Planting mast orchards can also provide a big boost when it’s needed most.

Winter

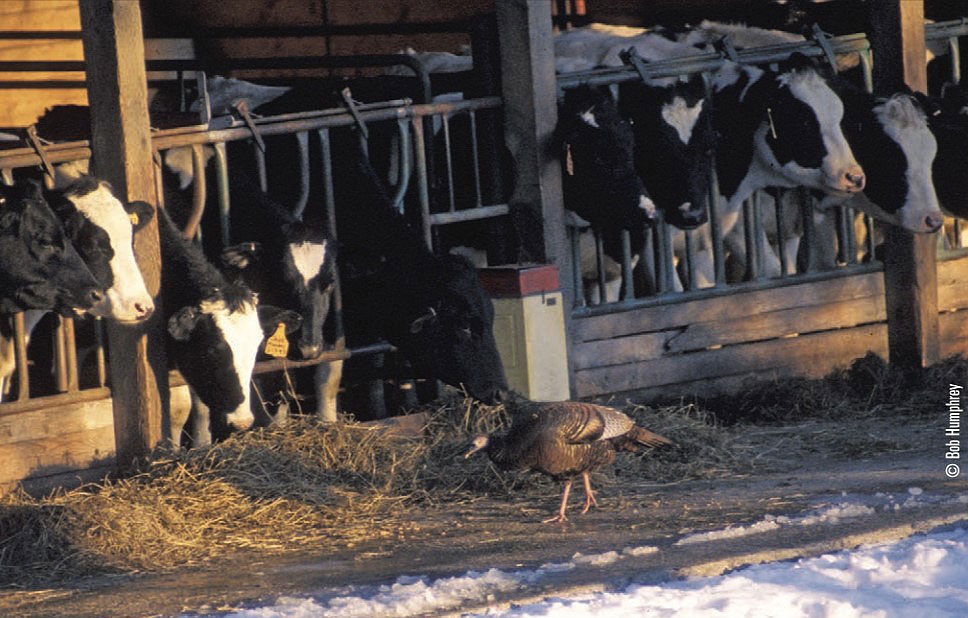

Winter is a time of scarcity; however, if you’ve done your due diligence in providing year-round nutrition for deer, there’s probably plenty of food out there for turkeys as well. There aren’t many substantial changes to a turkey’s diet when fall transitions to winter — it still often amounts to whatever is left and available. Obviously, it’s easier for these birds to search and find food in southern climates where snow doesn’t limit mobility or cover food. But even in the North country, turkeys still manage to eke out a living. They will often migrate to farms seeking waste grains and silage piles, and can even be found picking through manure. In some cases, turkeys can become more of a nuisance, particularly on dairy farms where they’ll literally tear the cover off silage piles and despoil it with their droppings.

More than any other time of year, winter is when landowners and managers may consider supplemental feeding. This method can boost production by carrying more birds through the winter, but it can also bring about certain inherent risks. Supplemental feeding concentrates turkeys into small areas where they are more susceptible to predators and transmission of parasites and diseases. A very important consideration to keep in mind is that the birds may become dependent on it. If you start winter feeding, try not to stop until ample natural food becomes available.

summertime diet and can make up as much as 80 percent

of a poult’s protein intake.

Spring

We end our nutritional calendar year in the spring for several reasons. One reason is to follow the chronological life cycle of a turkey from youth to adulthood. Another important reason is to save the best for last — a responsible gamekeeper wants to grow turkeys, but our ultimate objective is to be able to hunt them, and the best time to do that is in the spring. Find the food and you’ll find the birds.

Down to the last morning, it was looking like yet another turkey season would end for me in frustration. My last hope was an area I’d found while scouting the day before. There were ample signs, particularly along a small drain that was just greening up with skunk cabbage.

I got a bit of a late start, and the woods were already becoming visible when I stepped out of my truck. I was instantaneously greeted with a distant gobble — Hope springs eternal, and I immediately sprung into action, hastily halving the distance between me and the bird. Wary of getting any closer, I picked out a suitable backstop, plopped down and began my sweet serenade.

The gobbler obliged by firing up and heading my way.

“This is it,” I thought. “This might actually happen.” The bird was just out of sight when he went silent, immediately creating doubt in my mind. “What had I done wrong this time?”

Then I heard a strange sound — a deep, resonating moan, followed by soft footfalls in the leaves. Mosquitoes buzzed about my ears and stung my face, but I dared not move anything but my eyes. Soon, I caught a glimpse of movement, then a glowing red, white and blue head circling behind me. When he disappeared behind a brush pile I made my move — it was just enough to reposition my gun. The bird reappeared, pausing in my field of fire, and I squeezed the trigger. The feeling was indescribable when I walked up on my first turkey.

I began turkey hunting during the very first spring seasons in the northeast, and as a result, I lacked the benefit of a mentor. Veteran turkey hunters didn’t exist in my neck of the woods, so I had to learn by trial and lots of error.

One of the first things I learned was the importance of food. Find it and you find the birds. Turkeys begin the spring living off whatever is left over after winter. In my neck of the woods, a bounty of nuts and seeds is uncovered with the receding snow. But once green-up starts, the birds shift their diet to the lush new growth.

Another thing I quickly picked up on was that the first greens often appear in low-lying areas and along drainages. I also began to recognize certain preferences, skunk cabbage and Canada mayflower being among them. As the greenery spreads, so does the list of preferred foods, which can include dozens of types: grasses, sedges, forbs and hundreds of species. I’ve deliberately failed to list many of these options because there are so many variations across a turkey’s geographic range. Fortunately, there are plenty of resources that can tell you specific nutrition preferences in your area. Besides, half the fun is discovering it for yourself.

For those who might be inclined to plant food plots, I will mention a couple of options that top my list — my first food plot was clover. I built a clover plot primarily for deer, but soon saw it became a turkey magnet. Clover is one of the first things that comes up in the spring, and the turkeys are on it as soon as the first leaves poke through the frosty soil.

Not all clover plots are created equal, however — it all begins with the soil, and turkeys, like deer, know what’s good for them. They’ll walk through a poorly fertilized clover field to get to a good one. Sure, they may pick a little on the way, but they’ll spend most of their time where they get the best food.

the hunting season, both during the spring and fall. Here,

the author is pictured with his son and daughter, which

show the results of when the right food sources are present.

Another top-shelf turkey food is chufa. Unfortunately, I personally don’t have the right sandy, well-drained soil to grow it, but I’ve observed on places that do and it’s nothing short of phenomenal. Once the birds find the chufa and recognize it as food, they’ll absolutely tear up a patch.

However, there are a couple of caveats to keep in mind. One is that they may need a little help recognizing the chufa if you haven’t planted it before. As the plants ripen, turn over a few areas exposing the tubers. In most cases, that’s all it should take, and your birds should find it. Another potential problem is hogs (if you have them.) They like the chufa as much as turkeys, maybe more, and they’ll make quick work of your crop if you’re not vigilant in your control efforts.

Conclusion

In the final analysis, turkeys aren’t very picky eaters. They can eat a wide array of both plant and animal (insect) food and have adapted to survive on what’s most abundant at any particular time of year. In late spring and summer, young birds grow quickly on a steady diet of insects. As they grow, they shift to more plants, gobbling up soft mast during late summer and early fall and hard mast in late fall and winter. Turkeys are eager to take a hand-out from humans, whether intended or not. The more nutritious food a landowner and manager can provide, the more turkeys he’ll have to enjoy for the whole year around, especially during the all too brief spring and fall hunting seasons.