Jason Worley

The only name I ever knew him to be called was "Tuff." He was a native son of the Ozarks, and the one opportunity I had to hunt with him, he was nearly 85 years old. If my memory serves me right, that hunt fell in April of 1987. A close friend had called late one Friday night asking if I wanted to hunt with him and the old hunter. We were both teenagers at the time, doing all we could to learn to call in a wild gobbler. When the name Tuff came through the old rotary phone, I knew there was no way I would miss the opportunity. Tuff was known as one of the few remaining old-timers who had hunted turkeys during the early days, and many believed he was the best in a four-county area. The stories I heard would fill a book.

The stars were shining as my friend and I pulled up to the gate leading into his father's north eighty acres. It was a mixture of cattle pasture and hardwoods, and over the last couple of weeks, we had watched two gobblers strut each day in the middle of a pasture just past the gate. As my buddy killed the engine in the old Chevy truck, I saw the narrow set of headlights coming around the corner north of us. The little Jeep came to a stop in the county road and out stepped Tuff. He ambled across the road and stood at the door with a big grin on his face. "You boys made it, I see." With a sense of awe and a bit of fear, I managed to send forth a trembling "Yep, and it looks to be a good morning." For a kid obsessed with turkey hunting, I was in the presence of local excellence.

He quickly gave us a rundown of his plan, and since we had time, he showed off his tools of the trade there in the dim dome light of the old truck. Among his calls were an old handmade cedar box call and a little metal pill container. Trying not to sound too green, I asked him what was in the metal container. With wrinkled but nimble fingers, he popped it open to reveal his "mouth calker," as he liked to call it.

Diaphragm calls were nothing new to me, but I had not seen one without the tape that sealed it to the roof of the mouth. He picked up the call, popped it into his mouth, and within seconds the sweetest clucks and purrs I had ever heard were rolling out of the cab of the truck. "Don't like those new ones with all the tape," he said. "Like having a mouth full of newspapers." "Shoot, boys, when I started, we just grabbed a blade of grass or a tender young leaf.

The old hunter proceeded to give the two star-struck teenagers a lesson on how to use a diaphragm. I must admit, it took me at least another two or three years to get halfway good at using one. It was a labor of love, and little did I know that morning, I was listening to a man who had witnessed a large part of the history of the diaphragm call; a history we’re about to get into.

Before we get too far into this historical essay, let me clarify that I will often be referring to the diaphragm call as a "mouth call." For a full-fledged country boy like myself, it was several years into my journey at mastering the mouth call before I adjusted to it being called a diaphragm call. The phrase mouth call was used by every hunter I knew and it stuck with me.

With turkey hunting having deep roots in several locations across the country, we will likely never know where the diaphragm call got its start. I've heard many accounts of locals in different regions "inventing" the simple device we know today as the diaphragm call.

It is with little doubt though the first semblance of this call came from Native Americans using grass or leaves to imitate game animals. It should also be noted that several "leaf diaphragm calls'' were used in Europe to hunt game birds. Much like Tuff's blade of grass or tender leaf, these Native American and European calls functioned outside the mouth. Held within a crude wooden device or between the thumb and forefinger of both hands and slightly inserted into the mouth, these calls utilized leaves or grass, much like a rubber reed.

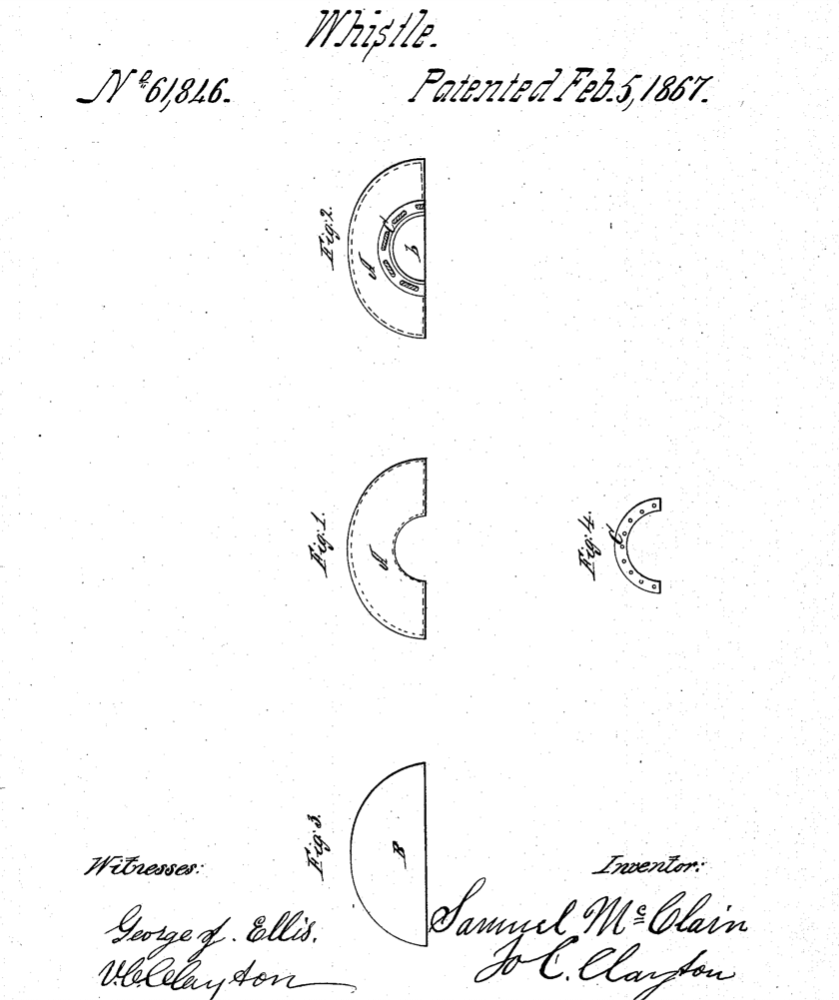

Many turkey hunters would be surprised to learn it was two years after the civil war when we see the first patented call that is undoubtedly an ancestor of today's mouth calls. In 1867, S. McClain filed a patent for what he called a "Whistle." The call is essentially a diaphragm call of today with leather in the place of tape and a tin frame holding a "thin skin, bladder, or similar material" as a reed. In McClain's patent, he states, "After a little practice, a person who has little taste for music, and is a tolerable mimic, can imitate all sounds from the deep grunt of swine to the shrill chirp of a week old chick." McClain never specifies the wild turkey as a possible candidate for mimicry with his call. Still, it is with little doubt it could have been used for calling turkeys.

It would be the 1920s when we see the next chapter in the story of the diaphragm call. As I stated earlier, it is tough to say who was the first to create the diaphragm call we know today. Still, through a bit of research, I feel safe in saying that the story of the production mouth call came down to two hunters from vastly different locations in the U.S.

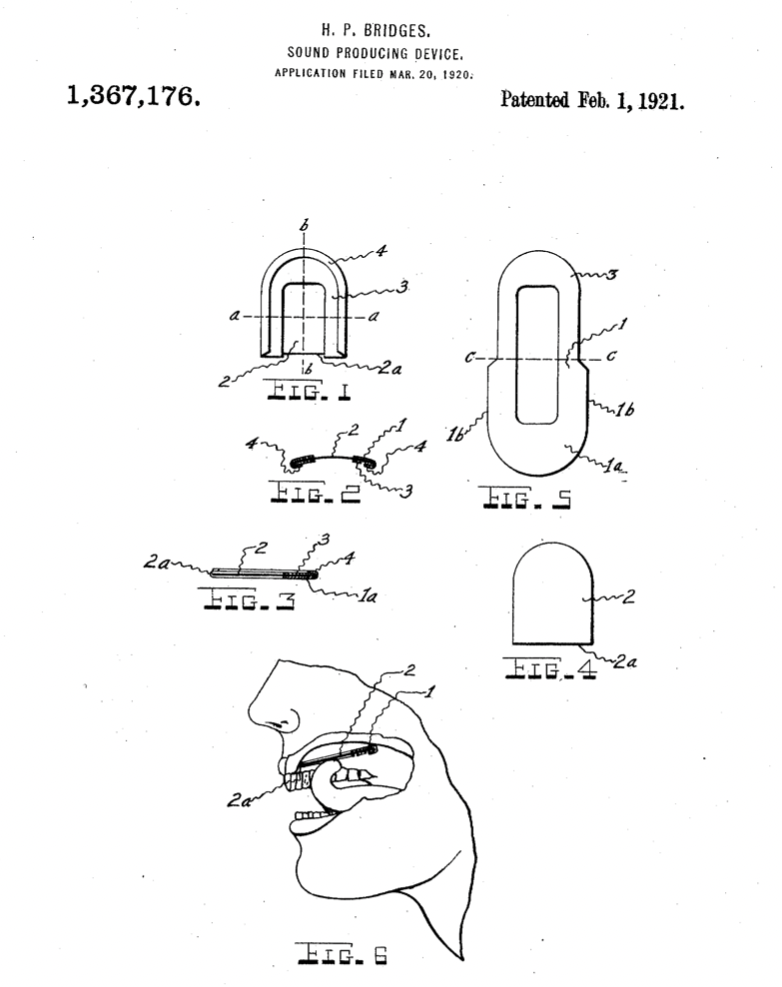

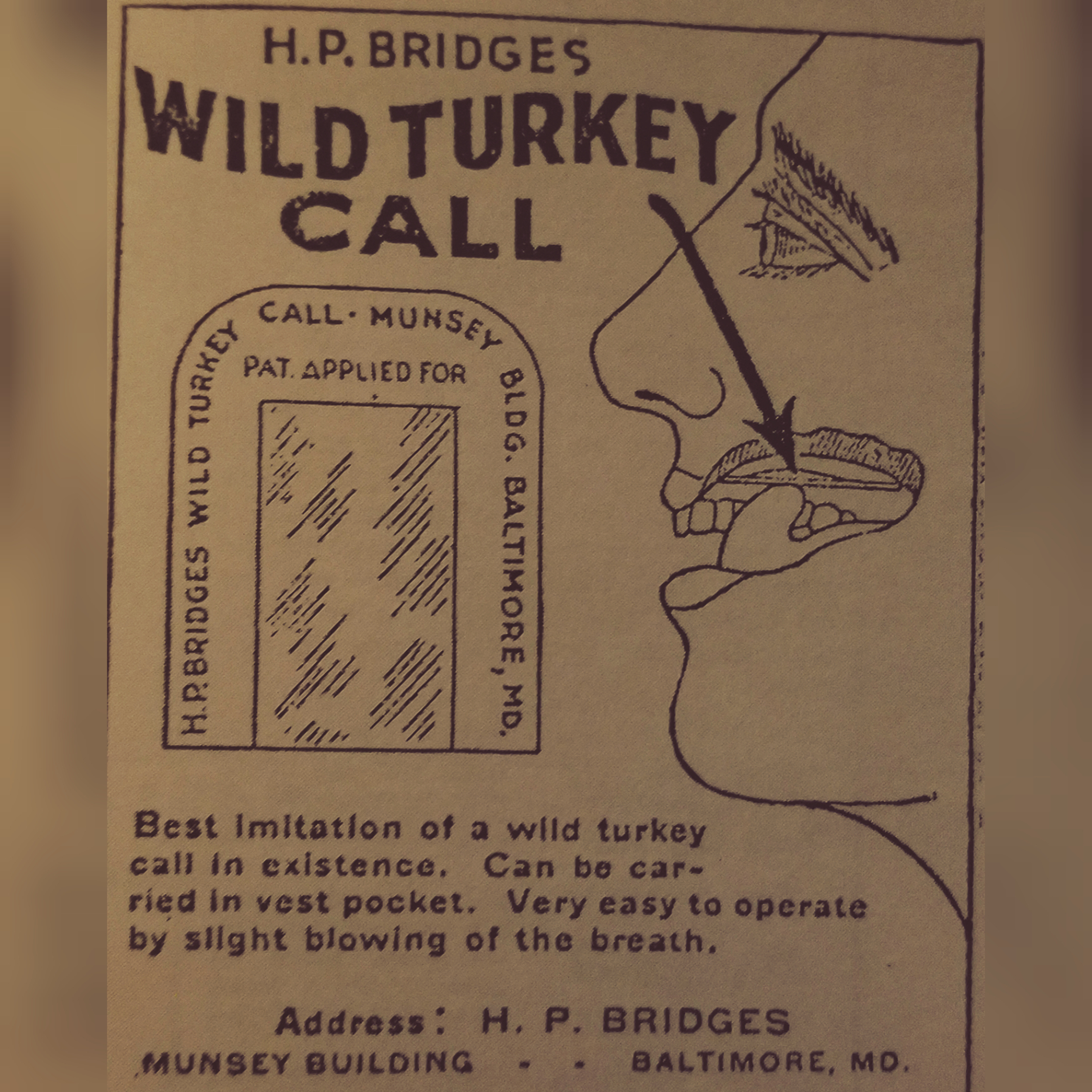

First was W.P. Bridges, from Baltimore, Maryland, who filed a patent in 1921 for what was called "A Sound Producing Device." One distinct detail of his patent is he calls out that it can be used in the hunting of birds and specifically the hunting of the wild turkey. In 1923 Field and Stream ran an ad for Bridges, "Wild Turkey Call." Like any advertiser trying to sell the latest and greatest invention, Bridges proudly calls it the "Best imitation of the wild turkey call in existence." I believe this is the earliest advertisement for a diaphragm call.

It was also sometime in the 1920s when a hunter from Mobile, Alabama, traveled to New Orleans to receive treatment for rabies. Jim Radcliff, Sr. spent his time in the French Quarters while waiting to complete the 21 shots in 21 days that were necessary to treat rabies in those days. While there, he ran across a ventriloquist who made bird songs with what was essentially a diaphragm call made with a lead frame and thin rubber reed. The ventriloquist made Radcliff a call, and so began his story of bringing the diaphragm call to turkey hunting. It's said that his mouth call was kept a tight secret in and around his Mobile home, but by 1953 it finally made its way into a magazine article, and the world discovered this new instrument of turkey calling.

So, who was the first to produce a diaphragm call specifically for turkey hunting? Honestly, it's hard to say with certainty. With the whistle of McClain's being in existence since 1867, one can't help but believe it may well have been the inspiration for either Radcliff's ventriloquist friend or Bridges. I will go out on a limb and say that excluding the McClain whistle, I find myself believing Bridges is the father of the modern mouth call simply due to the dates and patents mentioned above. Truthfully, though, who knows? Turkey hunters are an inquisitive lot, and to assume these two men were the only ones looking for a better way to fool a wild turkey would be a bit foolish.

The diaphragm call would see a massive surge in the 1970s and 80s, leading us to where we are today. The varieties and brands of mouth calls available today are almost mind-boggling, and few hunters haven't at least attempted to use the call. There's no denying the diaphragm call significantly impacted the tradition of turkey hunting.

Oh, and I'm happy to say, after Tuff's lessons that morning in the dim cab light of the old truck, he and those two teenage boys had a successful morning in April of 87. We set up on the two gobblers we had been seeing, and in a matter of about 30 minutes, the old veteran had both birds in the boy's laps. His little "mouth calker" had sealed the deal. One of those boys missed, and the other slung a long beard over their shoulder, which Tuff swore was the biggest he had ever called up. I’ll keep it to myself who it was that missed.