Tes Randle Jolly

Know the rules: It is legal on privately owned land but banned on public or government owned property like state parks, national parks, national monuments, national forests, Bureau of Land Management land and Corp of Engineers reservoirs. Digging, or probing underground for caches of artifacts is best left to professional archaeologists and illegal in many areas. The artifacts you find are another human’s personal possessions or burials. Read Artifact Hunting Basics for more on the dos and don’ts of artifact hunting.

As gamekeepers, we have a close connection to the land and wildlife. When we hunt, fish, work the soil and manage habitat we’re often on lands that connect us to the past where the original gamekeepers (Native Americans) did much the same. Native Americans revere Mother Earth, as the giver of all things necessary for life. Throughout history their cultures left historic evidence of their existence across the country in the form of artifacts such as arrowheads, tools, and pottery. From a hunter’s perspective, finding an arrowhead is awe-inspiring - to actually hold a weapon used by an ancient archer.

Recently, while scouting a game trail crossing a wide firebreak, this bowhunter spied the unmistakable flaked edges of a stone arrowhead. The point jutted from the soil alongside a fresh deer track, as if aimed for the animal that stepped over it.

In a whisper of thanks while reaching for the relic, a realization set in - these were the final seconds of a millenniums-old passage of time, ending with its discovery and my strong yearning to have met the arrowhead’s maker. The sharpened stone represented a tangible connection, if not spiritual kinship, with a fellow hunter from long ago. It had laid embedded in the trail’s soil, trod upon by generations of hunters and game. Finally, on that day, our paths crossed and the hand-crafted weapon was plucked from the earth and held once again in a hunter’s hand.

The point’s finely worked edges revealed the maker’s creativity and craftsmanship. Out of necessity and need, he’d chosen the stone, chipped with practiced pressure, and gave it a life of function and purpose. My imagination conjured up questions and images of what the man might have looked like. What was he wearing while chipping away at the stone, transforming it into the business end of a weapon? What tribe did the maker belong to? How old is the arrowhead? What type of stone is it? Was it shot at an animal or used in warfare? Was it a hit or a miss? Perhaps it was lost here. Whatever, this was a lucky day. Driven by a tendency towards superstition, (what bowhunter isn’t?) the weapon, now turned lucky charm, took on a new purpose and slipped easily into a pocket alongside my hunting knife.

Where to Look for Arrowheads and Artifacts

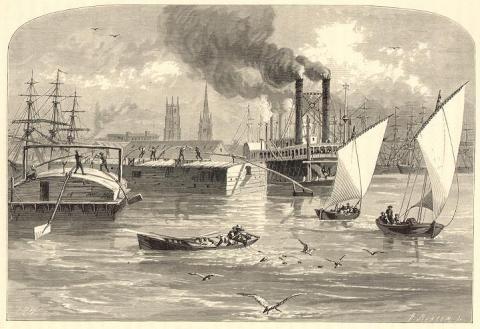

Early Native Americans were nomadic hunter/gatherers before later settling into a more agrarian culture. Artifacts are found in every state throughout North America, particularly near water sources. Water sustains life. It’s necessary for drinking but it also provided primitive cultures with food, transportation and hunting opportunities for animals coming to water. Native Americans established permanent settlements near water sources. Seasonal hunting and trading camps were also typically situated near some type of water source.

Think of the earth’s soil as flowing, similar to how rainwater flows towards rivers, constantly being moved by natural and manmade forces. Prehistoric Indian village sites may now be buried up to several feet below the ground’s surface due to silt deposits from repeated flooding and erosion. Over thousands of years, rivers and streams change courses. Lake levels rise and fall. As weather and natural conditions change, the water flow and channels, silt and soil also flows and forms terraces at the outer edges of the flood plain as waters recede. These rich soil areas above the flood plain were ideal locations for villages.

Today, as modern wildlife, timber and farming practices occur in these areas, rains expose artifacts after the soil is disturbed. Crop fields, wildlife food plots, firebreaks and power-line right of ways where soil is regularly disturbed are good locations to surface hunt for artifacts. Other places to consider are construction sites and areas where erosion occurs naturally, such as drainage ditches, gravel bars where feeder creeks empty into a main river channel, in cut banks along rivers and creeks and small feeder creeks leading to larger bodies of water.

A variety of items are typically found in village sites. These include waste rock, flakes, burned rocks, pottery and stone tools such as scrapers and drills. Arrowheads are also found, but many may be damaged or broken during chipping. Others are unfinished or rejects. Arrow-heads lost during a hunt could be anywhere. It’s a good reason to always be on the lookout when afield. Those found in an isolated setting such as a mountain ridge top or in the gravel of a creek bed are often whole and in perfect condition.

Walking a creek for artifacts is a great summertime family activity. The cool, wet environment provides pleasant conditions for searching gravel bars and cut banks. Some of everything in a watershed (think village sites) gets deposited in the gravel of gullies and creeks. However, not all creeks will contain artifacts. Rapid erosion typically occurs near head waters. Larger artifacts and fossils will be located there. Smaller ones will be swept downstream with rocks of similar size and weight. These settle on sand and gravel bars in quiet flow areas of the drainage. Creek finds may produce artifacts from widely different cultures and time periods.

Rock or Relic?

Most of us know the saying, “Necessity is the mother of invention.” In ancient times man’s greatest innovations and inventions were born of the need to survive and defend the tribe. One of early man’s most enduring creations was the development of stone weapons and tools during the Stone Age.

Early on, arrowheads or points (these terms include arrow points, bird points, darts and spearheads) were stones chipped to form a sharpened projectile or point. This process evolved into what’s called “flint knapping.” Native tribes used them in warfare and to kill animals as large as bison and mammoths on down to birds and small fishes.

For a novice artifact hunter, it can be difficult to tell whether what’s been found is actually an Indian artifact. It requires some knowledge of Native American history, flaking or chipping methods, a keen eye and patience to detect man-made markings on stone. With luck one may occasionally be spied lying in full view, displayed atop a pedestal of dirt. More often, there’s just a small edge of stone exposed.

A rock with a cleanly removed flake showing ripple marks on the flake scar was probably chipped by a Native American if found away from where heavy equipment has operated. One with multiple flake scars is almost certainly an ancient artifact. Don’t ignore stone flakes as just chipping debris. Flakes were often used as blades or tools. Examine large ones for evidence of shaping into drills or scraping tools.

7 Field Tips for Hunting Arrowheads and Artifacts

1. Use a Map

Use a topographic “quad” map (“quadrangle” maps usually refer to a United States Geological Survey map) to locate likely areas to search. Topo maps provide very detailed land topography, altitude, and waterways from major to small drainages. Google Earth and Microsoft’s TerraServer offer satellite imagery and aerial photos.

2. Hunt After a Rain

Hunt freshly disturbed soil right after a hard rain. Wet soil is a different color. Artifacts are usually easier to spot.

3. Handy Tools

Use a walking stick or an old arrow shaft to flip smaller rocks without bending over. An old toothbrush is handy to remove dirt when evaluating a find.

4. Search Carefully

Be methodical when searching. Walk in a sweeping fashion across an area in a grid. Mark each sweep when reversing course to avoid missing areas.

5. Go Early

Light direction affects how well artifacts show against soil. Early light is best. Late is good. Midday light is okay but it doesn’t create helpful contrasting shadows. In hot weather, midday high temperatures can also be an issue. Stay hydrated.

6. Secure Your Find

Perfect arrowheads or points are rare. Avoid carrying them in a pocket. The tip or barbs can snap and break. Wrap it in a handkerchief or paper towel. An ALTOIDS Mints tin is good to store finds.

7. Pay Attention

Keep an eye out for other artifacts such as stone or clay pipes, jewelry made of hard and colorful stones and pottery. Historic items may also be found like coins, musket balls, flint strikers, brass buttons, buckles and jewelry.

Identification Tips

Typing any artifact to the tribe and culture period opens the door to a wealth of historic information. About 1200 different arrowhead designs alone are on record made by Native Americans throughout the various culture periods.

Following are identification tips:

Identify the Source Material - Arrowhead type possibilities can be narrowed down by knowing the material type and where it originates. Early Native Americans utilized rocks such as chert, flint, and obsidian. Other source materials include wood, bone, and horn.

A tribe’s location influenced the type of materials used. Points made from alligator scales have been found in Louisiana. Native Americans in the Pacific Northwest used colorful stones such as agate and jasper. Arrowheads fashioned from petrified wood are more common in Arizona and New Mexico. Various metals were used after Native Americans encountered the first Europeans in the 16th century.

Shape and Design:

Arrowheads vary in size, shape, and thickness. They were attached to a shaft for shooting from a bow or to a handle at their base for throwing. Note if the point is stemmed, stem-less or notched. If it’s stemmed, what’s the shape of the stem? If it’s stemless, is the base fluted or not? If notched, note if it’s notched at the corner or the side. The design, size, and shape will further narrow the type possibilities.

Location:

Always record the location of finds. The exact area where an artifact is found helps further narrow the possible type, tribe, and culture period. It may also be helpful to find your way back to search for more.

Identification Guides and Resources

Each artifact is a treasure and a bridge to the past. When properly identified through its type, age, and purpose, an artifact gives us a glimpse into the lives of an ancient culture and its people.

Check out the following resources:

Local Archaeology Societies

Check for a list of state and local archaeology societies and archaeologists in your area. A professional can identify your finds. Joining a society can provide opportunities to meet other collectors attend seminars, participate in local digs, and observe local collections.

Reference Books

Books are a great first step to research arrowhead types. Keep in mind, not everything can be found on Google. Three popular titles include: “Arrowheads & Stone Artifacts: A Practical Guide for the Surface Collector and Amateur Archaeologist” and "The Official Overstreet Indian Arrowheads Identification and Price Guide" by C. G. Yeager. Two other options are “The Official Identification and Price Guide to Indian Arrowheads” by Robert M. Overstreet and “Arrowheads and Projectile Points” by Lar Hothem.

Author’s Note:

For collectors in the Southeastern U.S. check out “Sun Circles and Human Hands” Edited by Emma Lila Fundaburk and Mary Douglass Foreman.