Jason Worley

As I slid my kayak atop an old tree that had fallen months ago, I felt the cool October water trickle down my paddle and annoyingly soak through my worn shirt. There had been talk around the community that the fall colors were starting to show through the green hillsides surrounding the river, but I was in search of a different form of fall beauty. A particular shade of bronze, you might say.

The temperature had been slowly falling over the past few weeks, and I knew the time was near to catch that big smallmouth all river fishermen dream of. October can be a very trying month for a serious outdoorsman. The deer are just beginning to move, making bowhunting a constant thought, and that group of big gobblers that seem always to be chasing grasshoppers in the back pasture is constantly on the mind of a fall turkey hunter. And then there are those ferocious tigers of the river, the smallmouth bass that are feeding like fiends to prepare for the coming winter months.

Images of big smallies tail whipping the river's surface won the contest this Saturday afternoon, and I was hopeful that I would be able to tussle with a granddaddy fish. For years my father and I had paddled up and down this river in an old aluminum paddle john, and up until five years ago, I would be found in nothing but that beat-up ole' craft; that is until I discovered a kayak.

I was initially reluctant due to stories of unwanted swims and the fact that I like doing things the tried and true way. But, after trying out a few kayaks, I quickly discovered that the right kayak can be as handy as a shirt pocket. Now, I'm not talking about one of those brightly colored kayaks that carry the weekend warrior from the city, but a real fishing kayak. An ultra-stable craft that I can stand in and position nearly anywhere on flowing water. If I'm after big smallmouth, and I mean truly big bronzebacks, I won't even consider it a serious trip unless I have my kayak; it's become that important to me.

Regardless of the choice of watercraft, October is the month to be on the river in pursuit of smallmouth, and this afternoon, I was giving it everything I had in hopes of wrapping my hands around a bragging size fish.

I had just thrown a 4-inch crawfish-colored tube jig into a mass of boulders that had plummeted down from a towering bluff. Lord only knows how long they had been in the river, but it's those big rocks that I look for when chasing smallies. If they're in deep water with a bit of current boiling over and around them, you're sure to find fish.

Just as my bait settled to the bottom, I felt a hard tick, and my line began to move to the right. Lowering my rod tip, I cranked in a little slack and laid into the fish. My friends tell me one of these days, I'll end up pulling in a set of lips with no fish attached, but when I want to sink the hook in a fish, I mean business. The rod pulled tight, and a chunk of a 13-inch smallmouth shot out of the water and danced atop the surface. The fish continued to fight like a beast before I finally landed and released him. He wasn't the lunker I was hunting, but he put me in the mood for more.

Eight to 12-inch smallmouth are very abundant on the Niangua river, where I spend most of my time, and they aren't tough to catch either. A 1/4-ounce rooster tail or a 3-inch grub will catch fish all day. Couple those baits with a light action, spinning rig, and a fisherman can have a good time. But if you're in it for a big fish, and I mean anything over 16 inches, you need to change your game.

Just as big bucks behave like totally different animals, so too do lunker smallies. I remember my dad saying that if you want to catch a big smallmouth, you have to use big baits, find deep water, and fish slowly. A big smallmouth does not act like those 8 to 12-inch fish many people catch.

I have since learned that a little churning current, along with some type of cover, helps that deep water to produce good fish. A baitcaster coupled with no less than 10-pound test line is a must, and a medium to medium heavy action rod is needed for the backbone to handle a truly big smallmouth in current.

Dad always preached that big baits equal big fish and small baits equal small fish, so it's up to you what you want to catch. You may not catch as many fish as the guy standing next to you who's casting a small spinner, but the ones you do catch will make your heart pound and your back burn. There is no stronger fish that swims. Get that big fish in a little current, and you will question your success at putting him in the boat. Get him in a stiff current, and dad would say you will most likely be saying words your mother would disapprove of because chances are good you won't get your hands on him.

HOW TO TRAVEL WITH YOUR KAYAK: 9 HELPFUL TIPS

As I neared the center of the big eddy, I slowly dropped the anchor from my kayak and stood up. This hole is close to 10 feet deep, and several trees had been deposited on the outside edge during past floods. A good flow of current was pushing along the front of the trees, and I couldn't help but pick up my spinnerbait rod. Winging the big spinnerbait up river, it landed with a clatter, and I paused for just a second before I began my retrieve.

I always try to fish upstream so the current will naturally bring my bait down with it, but when fishing a spinnerbait, this can cause problems with getting the blades spinning. To remedy this, I like to pause for just a second to allow the bait to get down a bit, and then I kick my retrieve into high gear for several cranks. This gets the blades turning, and then it's a matter of retrieving with the current just enough to keep the blades thumping. You have to almost feel the bait to know it's doing its job.

Just as the big double-bladed spinnerbait came off the end of a log, I felt the unmistakable slam from a smallmouth. I set the hook hard and immediately knew I had a good fish. She turned with all her might and pushed hard to get back into the trees that had been her hideaway moments before. The heavy rod and casting reel did their job as I turned the fish back out into the mainstream, but now she was into a stiff current. She shot out of the water like a rocket, shaking her head. I was sure she would free the hook, but as she hit the water and dove for the bottom, I felt the strength that only a smallmouth has. She was still hooked!

She continued to turn, twist, and churn towards the bottom, but slowly I worked her close to my kayak. My heart was in my throat, and I was shaking like a scared kid. This was a dandy fish and by far one of the better fish I had caught all year. Finally, the old girl came to the surface beside my boat and laid on her side just long enough for me to get my hand in her mouth and hoist her into the kayak. She was a beautiful 18-inch bronzeback.

I paused for a second to admire a fish that was probably the same age as my 10-year-old niece. She was a masterpiece of natural beauty and a fighter of incredible strength. I quickly snapped a couple of pictures and then lowered her back into the calm eddie. Just as my father taught me to catch those big fish, he also taught me that they must be released. Most of those bigger fish are females possessing the genes that need to be passed on. If you are bent on taking a few fish home, keep the 12 to 14-inch fish and let the big ones swim again. Dad fished for food, but when it came to smallmouth, he laid aside his want for a meal and truly cared about the future of river smallmouth…a true conservationist.

The fish pumped its tail a couple of times and disappeared into the deep eddie. I laid my rod down and lowered myself to my seat to let my nerves calm a bit. Gazing into the surrounding hills, I couldn't help but feel like I had traveled back in time to an earlier day when the river was even more alive than it is today. A time when this eddie was 20 feet deep, and the small spring just up the hill still flowed freely. A time when the river wasn't choked up with gravel and silt and massive oaks stood like sentinels of a better time.

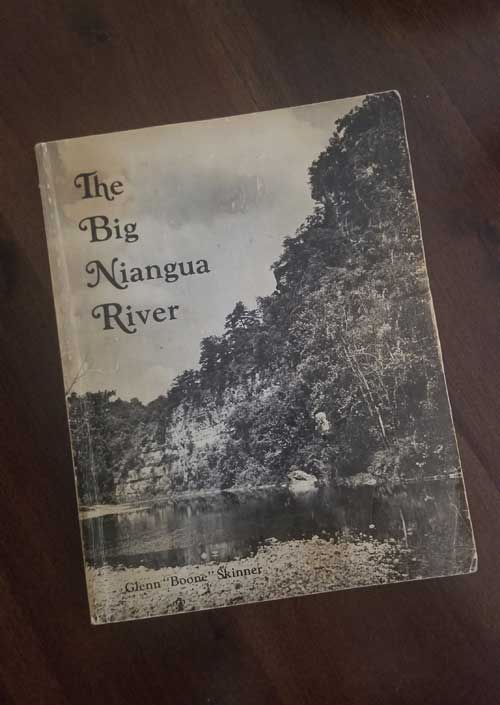

As my nerves began to calm, I began to think of a long out of print book I had recently acquired. In 1979, Glenn "Boone" Skinner wrote a book entitled "The Big Niangua River." In it, he describes the Niangua like few ever have, a true lover of the free-flowing water and all life within it. In his final paragraph, he writes, "Man may mar and injure the land, degrade and pollute the river to the extent of annihilating himself. But after the dust and the smoke of so-called progress have settled and vanished, time at the charge of God beckons nature to remove the ruins and build anew." Men like Skinner knew we must take care of our rivers, streams, and all of nature, because, in the end, it's not so much a question of whether mother nature will continue to exist, but instead a question of will we continue to exist.

Looking at the surrounding trees, I noticed just a touch of those colors the locals had talked about. The yellows were showing up in the hickories that stood atop the ridge above. I knew it wouldn't be long before the Virginia creeper and the sumac began to put on their coat of red, and the oaks would glow with an orange tint. Many folks come to the rivers in October to enjoy those colors of red, yellow, orange, and every variety thereof, but for me, it's all about that beautiful shade of bronze.