Steve Damarais, Bronson K. Strickland and Marcus Lashley, MSU | Originally published in GameKeepers: Farming for Wildlife Magazine. To subscribe, click here.

Acorns dropping from oak trees and fall food plots often receive a lot of attention from deer, and anything that draws the attention of deer will certainly be of interest to deer hunters! Oak trees and their acorn crops are great to have as part of deer habitat, but sometimes they receive too much emphasis. They are great to have around as a “dessert” for deer and a commercial timber product, but the presence of oak trees is not a prerequisite for an effective deer management program. In fact, an expansive mature hardwood bottom chock full of mature oaks would be a literal foraging “desert” nine months out of the year and a great place for coyotes to eat up young fawns. Fall food plots attract hungry deer, and cozy stands on their perimeter offer a focal point for deer hunters. However, if hunters want to really help their deer population nutritionally, they are better off focusing their seed planting skills in the spring.

To fully understand these statements, you need to understand some biological background that determines what deer need nutritionally and when they need it.

Physiological Demands and Related Nutritional Needs During Summer

where nutritional demands are high; gestation or the growth

of their fetuses, and lactation until her fawns are weaned.

The physiological demands of deer determine their nutritional needs and thus their habitat requirements. There are lots of analogous situations in the human world. Guys and gals that participated in highly active sports during high school could eat large quantities of food and remain in good shape because their physiological demand balances their nutritional intake. But, maintaining those same “foraging rates” after graduation is a sure fire way to add weight to your midsection.

Deer have dramatically different physiological demands throughout the year that also affect their nutritional needs. Demands differ for males and females, so we’ll describe them separately. The physiological and nutritional demands of antler production last from March through August. The majority of antler growth takes place during May through July, with August primarily being a period of mineralization or hardening.

Generally, nutritional management for optimum antler production covering a variety of ages should strive for an average intake of 16% protein. It is generally accepted that any forage that fulfills an animal’s protein requirement will also fulfill their energy requirements. Adult females also have two primary demands each year: gestation or the growth of their fetuses and lactation, which is the production of milk used to raise their fawns until they become self-sustaining.

Demands of gestation are most critical during their last trimester. Lactation demands are critical from birth until fawns are weaned at about 3-4 months of age. Gestation and lactation protein requirements are met by a 16% average crude protein diet. To summarize, summer is a physiologically demanding and potentially limiting period nutritionally for whitetails. Habitat should meet this need by providing an average diet quality of 16% crude protein during this period.

Deer Habitat Quality

food during hunting season, but what about the rest

of the year. While it’s almost impossible to compete

against acorns, they are only available for a limited

time. A manager should strive to provide quality

food the year-round.

Whitetails have amazingly flexible habitat requirements that allow them to live successfully within a wide range of habitat types, from areas dominated by agriculture, to those with mostly forests, and even successfully deal with regular flooding events or drought. Their primary habitat requirement of concern in most areas is adequate quality and quantity of forage below 6 feet (i.e., nutrition). Hiding and escape cover for fawns are also important. Both of these needs are best made available in forested areas through the process of timber harvest.

Canopy removal during thinning and/or clear cutting makes sunlight available at ground level, which leads to forage production. Diet selection by deer changes in response to seasonal changes in forage abundance, quality, and metabolic needs of the animal. Deer eat a variety of food types throughout the year, including browse (leafy parts of woody plants), forbs (herbaceous broad-leaved plants, including agricultural crops), hard mast (acorns, pecans) and soft mast (persimmon, muscadine, apples, blackberries), grass and mushrooms.

As a general rule, deer need browse, prefer forbs, and relish mast. They “need” browse because it is the most stable forage supply due to its relative independence from rainfall. Deer “prefer” forbs because they generally are more palatable and higher in protein than browse. Deer “relish” mast just like people relish dessert because it is a highly palatable source of energy with moisture included.

Habitat Management Context

Aside from population control, forest management has the most important influence on deer populations over much of their range. The production of understory vegetation is related directly to a number of factors including site quality, forest type, and stand age and structure. Abundant deer forage is produced only when sunlight, space and nutrients are available. Sunlight regulates the growth of forage in the understory first. So, timber harvest that allows sunlight to reach the forest floor stimulates the production of desirable herbaceous vegetation, woody vines and other browse species which are of high nutritional value to deer and also provides escape cover.

Young clear-cuts may provide abundant forbs, vines, woody browse and soft mast for a limited time, depending on the type of site preparation and release procedures used during planting. Again, forage production is limited mainly by the availability of sunlight so the type of stand establishment will affect available forage, and this effect is not necessarily consistent in all areas. For example, in the Lower Coastal Plain of Southeast Mississippi, removal of low quality woody vegetation using a chemical site preparation made sunlight, space and nutrients available for higher quality forbs, which increased nutritional carrying capacity for deer. However, in a similar study in the Coastal Plain of North Carolina, forbs did not respond positively to woody browse removal, so treatment effects are definitely site specific.

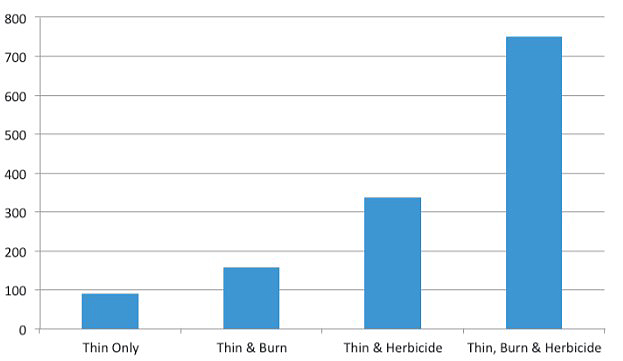

Additional relationships may be evident in other soil regions, depending on soil and plant quality, so it’s impossible to make a definitive statement that applies to all areas. However, in general, forage production will almost always be greater in forest stands that allow sunlight to the forest floor than stands in similar areas that do not. Production of understory forage declines dramatically with canopy closure. For example, in loblolly pine plantations in the Mississippi Coastal Plain, nutritional carrying capacity declined 95% from 2 years post establishment to canopy closure at year 7. Carrying capacity remains low until the stand is thinned for pulpwood, which typically occurs first at 13-17 years in southeastern pine plantations. Prescribed fire is an excellent tool that can be used in combination with timber harvests to stimulate and maintain the availability of high-quality forage and cover in pines (Figure 1), but also upland hardwoods (Figure 2).

Prescribed fire applications following initial and mid-rotation thinning, and thinning later in the stand rotation improves germination and growth of high quality herbaceous plants, further increasing food production for deer. Additional fires are useful every 3-5 years to reset vegetation height to in reach of deer, but it is imperative to remember that sunlight must reach the forest floor to gain the maximum benefits from prescribed fire. Most pines and upland oaks, such as post oak or white oak have thick bark or cambium layers that allow them to survive mild understory fires without damage. For example, a study in Tennessee demonstrated that thinned stands dominated by white oak and chestnut oak were not damaged by repeated cool-season fire and maintained high-quality deer habitat.

Additionally, early bow season hunters and deer will enjoy reduced parasite abundance, particularly immature stages of ticks, following controlled burning. In addition to annual changes in forage quantity due to timber management, there are seasonal changes in forage quality due to normal plant growth stages.

Fresh, new growth is highest in protein and digestibility, and these important nutritional components decline as much as 40% once the plants stagnate due to hot summer temperatures and lack of rainfall. This occurs nearly every year during the late summer in what we call “the late-summer stress period.” For deer that occurs as the high-quality forage plants senesce and before acorns are available but deer nutritional requirements are still relatively high.

The Role of a Food Plot Program

Many hunters and deer managers don’t have the ability to implement the forest management techniques we have discussed simply because they don’t own the property they hunt – they lease the land. The authors of this article fall into this category – we know what needs to be done to produce good deer forage, but because we don’t own the land, we are at the mercy of the landowner.

Many hunters and deer managers don’t have the ability to implement the forest management techniques we have discussed simply because they don’t own the property they hunt – they lease the land. The authors of this article fall into this category – we know what needs to be done to produce good deer forage, but because we don’t own the land, we are at the mercy of the landowner.

In these cases, habitat management becomes a combination of deer population control and a good year-round food plot program. So how many deer need to be harvested on your property to keep the population in check with the available habitat? Well, there’s no good answer because it varies from place to place an-d over time, but you can use your food plot program to determine if you have too many deer.

The success of a food plot program goes hand and hand with deer numbers. There’s just no way to accomplish your objectives of improving deer diet quality if you have too many deer! If year after year you fail to establish a warm- season food plot then you have too many deer. Make sure every food plot has an “exclusion cage” (or browse cage) so you can determine if your plot was successful. To raise deer diet quality and to fulfill the summer requirements we described above, you need to establish a year-round food plot program. “Green fields” in the fall and winter are good for seeing and harvesting deer, but not for improving summer diet quality, and subsequently deer body weight, antler size, and reproduction.

Your food plots must support the physiological demands during antler-growth of males and late-gestation and lactation of females and supplement the seasonally declining quality of stagnant, naturally-produced forages. The warm-season food plot plants do a great job of providing large amounts of high-quality forages and are particularly useful to address the late-summer stress period for deer. Warm-season food plot choices should include high-protein producers, like forage soybeans.

If you have a high deer density or smaller plots (<10 acres) you may need to install a single-strand electric fence to protect the soybeans until they reach about two feet tall. Alternatively, you may want to consider cowpeas, lablab, or deer vetch (American joint vetch) as they are more browse tolerant. Alyce clover or buckwheat may be the best choices for high deer densities and smaller plots because they are the least preferred of these warm-season forages. Having a portion of your food plots in perennials stabilizes the forage supply.

One of the best forages is alfalfa, but it can be difficult to establish and is time consuming to maintain. The most common perennial food plot choice is white clover because it is relatively easy to establish and if you continue to fertilize with P & K and keep the weed competition low with timely herbicide applications you can get many years of production. (For planting rates please refer to the publications listed at the end of this article or download our free iPhone app “DeerPlotApp” from the iTunes store).

Management Context

Deer need a seasonally and annually stable supply of food that fulfills their protein requirements. Opening of the forest canopy via timber harvest is the primary mechanism for production of forages that will provide a nutritionally adequate and stable deer habitat in regions dominated by forests. And, sound forest management provides one of the most important resources to deer food plots do not cover. Supplemental summer forage plantings provide important nutrition when wild forages are declining in quality, especially during the late-summer stress period.

When planning your deer habitat management program, prioritize your efforts to produce year-round natural forage quantity and quality using timber harvest. Timber harvest should be planned to optimize forage production across your property. Then, consider a mix of seasonal and perennial food plots. So, remember, the foundation of your deer habitat management program is production of a year-round supply of palatable, high-quality forage.

By Steve Demarais, Bronson K. Strickland, and Marcus Lashley Deer Ecology and Management Lab, Forest and Wildlife Research Center and MSU Extension Service, Mississippi State University