Todd Amenrud | Originally published in GameKeepers: Farming for Wildlife Magazine. To subscribe, click here.

There are numerous plants classified as legumes (“Fabaceae” family) and they can be annuals, perennials or biennials. All types can be used in agriculture and wildlife management, but annuals can be especially productive when managed properly. Many annual legumes grow a fruit that develops from a simple carpel that forms a pod and these pods produce foods like beans, peas, lentils and peanuts. Some legumes are also grown for livestock feed because of their prolific production of high-protein, very digestible forage. Another huge bonus of legumes is their capability to fix nitrogen to the soil through bacteria contained in little configurations called “root nodules,” so they also make great soil-builders for rotation, a cover crop or soil-enhancing “green manure.” As gamekeepers we can take advantage of all of the above.

Legumes include perennials like alfalfa, clover, trefoil and vetch; and annuals like peas, beans, lentils and peanuts. There are also legume trees like the locust tree or the Kentucky coffee-tree. Perennials are important because they are up in the spring before any annuals have begun to germinate, but for your herd to really “put on the feed-bag” nothing can compare to the tonnage produced by annuals. Soybeans, iron & clay peas, lablab and winter peas make up the better share of annual legumes most often planted for whitetails. Understanding these legumes and how to best utilize them can help you to attract and hold more deer grow bigger antlers and take your management efforts to the next level.

Soybeans

Soybeans are the warm-season annual legume most planted for both agriculture and wildlife management - they may also be the most favored by whitetails. Soybeans come in too many varieties to list with a wide array of characteristics to help managers achieve most any goal a bean could possibly assist with. Some are great forage producers; some produce a great bean yield while other varieties give you a combination of both. They are very nutritious, palatable and digestible, containing between 20% and 30% crude protein, depending upon the part of the plant considered and the stage of growth.

As mentioned, soybeans can be categorized as either grain creators or forage producers. Soybeans sold for grain production are characteristically shorter and stand more erect. Their goal is to grow up and produce the best bean possible in the selected maturation period. Forage soybeans, on the other hand, usually grow taller (some 7 to 8 feet tall or more) and tend to vine-out and grow bushier which helps to increase leaf forage production and protect the terminal bud. So if you wish to grow an actual bean for late season attraction or wintertime protein, a grain soybean would be your best choice. However, if you want to produce tons of green leaf matter for antler growth, fawn rearing and summertime nutrition, then forage soybeans should be planted.

Soybeans are easy to plant and easy to establish in a wide range of soil types. They can be planted by drill or broadcast and covered, and like other legumes they prefer a neutral pH. Just like all of the annual legumes we’ll be talking about today; you must plant enough to overwhelm the amount of mouths you have to feed. You must reach what I refer to as “terminal yield.” The point at which you not only meet, but surpass the amount of plants needed for the majority of your crop to grow un-browsed to the point when they begin to vine and become prolific enough to keep up with a realistic amount of browse pressure.

bag” and warm season legumes will be on the menu if there

are any within their range. Not only are these legumes

attractive to whitetails, but they are also great nutrition –

high in protein and very digestible.

One must also mention the fact that many soybeans come in Roundup Ready varieties. This makes them easy to plant and grow weed-free. The downfall is expense. Roundup Ready soybean seeds were introduced in 1996. From 1995 to 2011, the average cost to plant one acre of soybeans has risen 325 percent! On average it’s about twice as expensive to plant a glyphosate resistant bean as opposed to a regular soybean. The soybean used in BioLogic’s BioMass and BioMass all Legume is a bean that will produce both, forage and grain, but without the cost of a Roundup ready bean. It must be noted that you can still prevent grass competition with an application of one of the many clethodim or sethoxydim-based selective herbicides on the market - they are safe to spray over BioMass all Legume or Lablab.

Despite the overwhelming number of soybean varieties, deer really are not particular when it comes to eating them. I’ve never seen a variety deer won’t consume, however, a specific type (or group) of soybeans may help fulfill your specific objectives. For example, if you live in the South with a long growing season where late summer is typically the most stressful time period for deer, a later-maturing forage soybean will ensure ample forage is available during the critical August and September months when natural food sources are low. Conversely, if you live in the North with a shorter growing season and you are more concerned about having standing beans (grain) to hunt over during late winter, then an earlier maturing, bean-producing variety may be better suited.

Lablab

It is said that lablab was originally brought into the United States from Australia. Wherever it came from, there’s no doubt it was made famous for whitetail management in Texas. There, researchers showed that lablab improved antler size, body weight and herd density, but it was proven to do all of this under some of the harshest growing conditions in the country…as I said, it’s Texas. A downfall is just like other annual legumes that are susceptible to browse pressure, lablab seems to be doubly so. Lablab is not the best choice for small, unprotected monoplots - it should be planted in large plots or protected with fencing and/or repellents.

Lablab can be successfully grown anywhere that soybeans and peas will grow. The standard ratio is about 20 lbs of seed to an acre and will grow in any type of soil pending adequate soil moisture is present and it is well drained. It is very drought tolerant once established but does not grow well in wet soils. It can be planted with a no-till drill or broadcast onto a well-prepared seedbed at a rate of at least 20 lbs per acre and then covered with ½ to one inch of soil. It should be planted during the spring when soybeans are being planted in your area or once the soil temperature reaches 65° F or higher.

Whitetails are strongly attracted to lablab’s large, succulent leaves and you should expect utilization shortly after germination. It has a fair list of pros for a whitetail manager. It should produce about four tons of forage per acre at about 25% protein and is very digestible. It has calcium to phosphorus ratio of 2 to 1 making it an especially good choice for antler growth. It is very tolerant of browsing once established, but it is vulnerable to browse pressure for the first 30 days of growth. As mentioned, in small plots it’s wise to protect it with P2 Plot Protector for the first month if you anticipate browsing pressure

annuals like cereal grains, brassicas or other legumes.

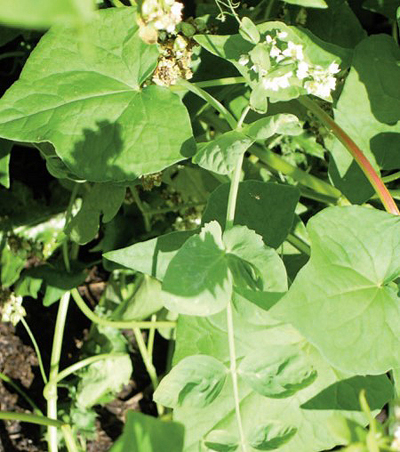

Here you see the winter peas in Hot Spot.

Lablab is extremely drought tolerant and likes the heat, but will be finished at the first hint of a frost. Once it makes it to the point of starting to vine (about 3 to 4 weeks after germinating) it becomes very vigorous. It’s resistant to insects and disease, grows well even in rough or acidic soil and produces an incredible amount of forage.

Iron & Clay Peas

Iron & clay peas are another warm-season annual that can be grown throughout the United States and planted from May through August. They are often called cowpeas or black-eye peas, but this legume is actually a bean that produces highly-digestible, large, triangular leaves that are very attractive to deer. And just like all our legumes on the list today, you’ll have to keep the deer from engulfing them before they start to vine and are able to put on substantial growth.

Cowpeas can be planted throughout most of the country from May to August. Later plantings can provide succulent growth to attract deer for an early bow shot. Cowpeas do well in a wide range of soil types, but do best when planted in well-drained soils. They will also tolerate more acidic soils than most other legumes (pH as low as 5.0) and are a bit more tolerant of cold temperatures than lablab and many varieties of soybeans.

Iron & clay peas can be drilled at a rate of 30 to 50 lbs per acre or broadcast at a rate of 50 to 75 lbs per acre and covered with about one inch of soil.

The forage is relished by whitetails, but iron & clay peas are also great food for upland birds and turkeys. Turkeys will eat the newly emerged seedlings, but when the seedpods dry and shatter they become food for upland birds, turkeys and other animals. Whitetails primarily feed on the leaves during the summer, they especially favor the young, tender plants.

Iron and Clay peas are planted more often in southern states for a summertime food plot crop than in northern latitudes. Seed (bean) pod production is highly dependent upon temperatures and the amount of sunlight, and when planted in the north they will often not produce any seed pods. Luckily whitetails go nuts for the forage, not the fruit. They are more attracted to graze on the forage leaves of this southern plant.

Iron and clay peas are an excellent choice to mix with other plants to create a smorgasbord for your herd. They pair well with corn, sorghum, sunflowers, cereal grains and other cultivars, but do especially well with the other legumes on our list. BioLogic’s “BioMass all Legume” features soybeans, iron & clay peas and lablab blended together in a versatile, vigorous spring/summer planting. The combination of these warm season legumes gives you attraction power, the ability to do well in almost any growing condition, teeming tonnage production and the capability to treat the blend with a selective grass herbicide (clethodim or sethoxydim) for a clean, legume-only stand.

Personally, I will usually go with BioMass all Legume or a variety or blend of Roundup-Ready soybean(s). RoundupReady beans make it easy to claim a new area with a warm season planting. If grass will likely be my only nemesis, then BioMass all Legume is the way to go for several reasons. One, because it’s a blend of legumes - you have three cultivars working for you expanding your palatability timeframe significantly. Two, I can still treat the plot with a selective grass herbicide (like Weed Reaper) to reduce most of the competition. And three, expenses – BioMass all Legume is less expensive. When planting a few acres it adds up.

Winter Peas

As opposed to the “warm-season” legumes already covered, winter peas are a “cool-season” annual legume that can produce a great food plot on their own or as an addition to a blend of other plants, primarily used to attract whitetails for hunting opportunities. This is the “go-to” legume for fast attraction for a late-summer/fall planted hunting plot. Once again; however, “terminal yield” must be achieved or a few deer can wipe out a small plot before the hunting season ever begins.

Winter peas are easy to grow, quick to germinate and are extremely palatable right away after they pop out of the ground. They are closely related to the peas we grow in our gardens and have the same nitrogen-fixing abilities as all of our featured legumes. They are highly nutritious, extremely digestible, and carry a protein level between 20 and 30 percent. They don’t do well during a drought, but they do have good winter hardiness, especially when compared to the other legumes on our list. They form vine-like growth and can reach lengths of five feet or more in good growing conditions.

Winter peas can be broadcasted at a rate of 40 to 70 pounds per acre and covered with ¼ to ½ inch of soil (no more than 1 inch). Seeds can also be drilled at a rate of 30 to 50 lbs per acre and are typically planted from August in the north through October in the south. In northern climates they are sometimes planted during the spring and grown as a summer annual. Winter peas do best in well drained soils with a pH of 6.0 to 7.0.

While winter peas can be planted in a mono stand, unless the plot is large enough to survive heavy browsing it will be Four Bean Salad continued better able to withstand pressure when planted in a blend with other annuals like cereal grains. Winter peas are like candy to whitetails.

Annual legumes, both warm-season and cool season, should be on a manager’s menu if they have sufficient acreage to devote or a way to protect them. Electric fence or P2 Plot Protector will work to get the plants to around four weeks old, and then they should be able to keep up with the pressure much easier. “Terminal yield” must be realized. They must be protected or enough must be planted to overwhelm the amount of existing pressure. Once past that point, all these annuals can pump out tons of attractive, protein-rich forage.

While the warm season legumes can make a very attractive early season bow plot, they are primarily used for summertime nutrition. Soybeans that have dried on the stalk can also be late season attraction and wintertime nutrition, but for the most part, it’s the green leaf forage that managers take advantage of during the summer months. On the other hand, winter peas are most often planted for hunting season attraction. The tender, tempting leaves are too much for a whitetail to resist. All of these legumes, although some planted and utilized at different times, are like the perfect four bean salad for your herd.