Written by Jessi Cole

In an unassuming building in Knoxville, Tennessee, a small and devoted team of nine biologists work to restore the southeast’s rarest and most vulnerable non-game fish species, species sometimes only found in one particular stretch of a stream high up in the Smokies.

Conservation Fisheries, Inc., also known as CFI, was the first private hatchery to make these little vulnerable fish, fish like the Smoky Madtom and Bluemask Darter and Barrens Topminnow, a priority to save and protect. Over the course of their 36 years, CFI has successfully propagated over 75 fish species and introduced close to a quarter of a million fish back into waters around the country and especially around the southeastern United States.

The same threats to rest of wild populations exists to these species—deforestation, invasive species, mining, and habitat fragmentation, to name a few—yet these forgotten little jewels of fish in freshwater streams and creeks have been made to take a backseat to game fish conservation efforts and even trophy game fish management.

But these fish are important, too. They serve as a vital link in the aquatic food web by feeding on macroinvertebrates and then growing large enough to entice a larger fish, like a trout or a bass, and becoming prey. Several of these smaller fish species also are important reproductive hosts for freshwater mussels, which work tirelessly to filter out pollutants in the water.

Bluemask Darter rests in a small stream. Photography by Derek Wheaton.

As a fly fisherman, I’m certainly guilty of only thinking about wild trout. I watch video after video of conservation work done by organizations to preserve popular game fish species wild browns, wild cutthroat, and native brookies, and yet I’ve never once thought about how the other, littler fish that live in some of the very same streams are handling the threats to the habitats.

After seeing an Ichthyologist I follow on Instagram visit Conservation Fisheries and post photos of delicate, colorful fish darting around tanks, carefully monitored by a team of professional biologists, I realized how blind I had been to the conservation of all fish and not merely just my beloved trout.

After reaching out, CFI was happy to welcome me for a day of discovery and to learn more about their work. Arriving early one Friday morning, I sat down with a few passionate biologists and was given a detailed and fascinating tour of the facility, a facility that didn’t waste a square inch of space; filled with tanks and equipment and plastered with artwork of freshwater fish and mussels. They display a proud collection of conservation awards they’ve received for their hard work on top of a shelving unit; space for fish takes priority over any sort of egotistical pride.

And the amount of work that goes into the care of each fish, each species, is astounding. An entire room, filled with probably 50 or so containers, is dedicated to raising the tiniest arthropods, rotifers, and worms I’ve ever seen to feed the fish in all stages of their life cycle.

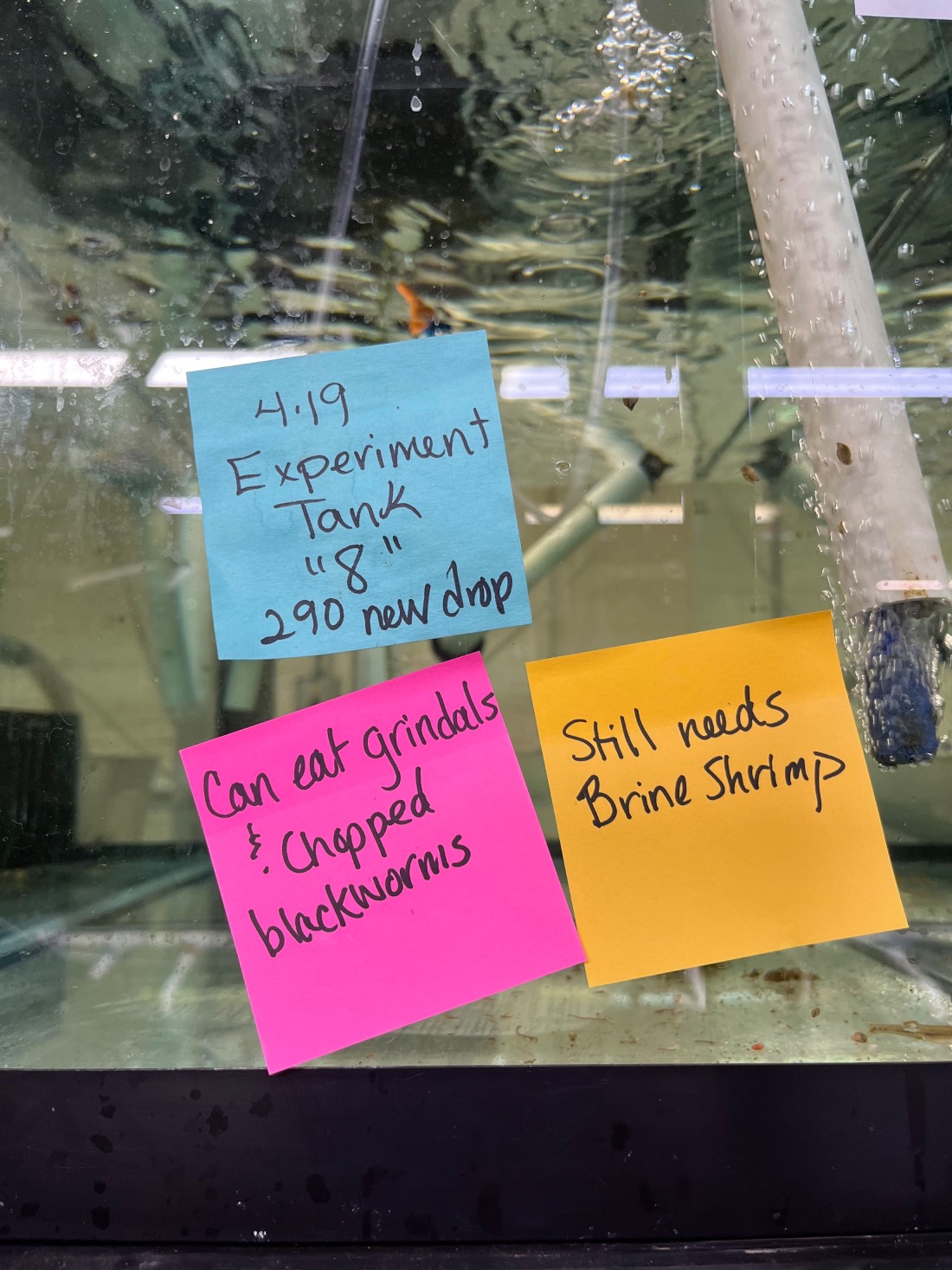

Each species receives their own recirculating system to hold water temperatures and conditions at the exact right way for that particular fish; each tank holds fish at different stages in their life cycle. Breeder fish swim in one; the collected eggs are then transferred to a second tank, where the fish, once hatched, will continue to be transferred to an assembly line of tanks, each marking a different point in the life cycle.

I peered down into waters filled with little iridescent, orange eggs that had a two large dots in the middle, dots which I was told were the eyeballs of a baby fish. Bo Baxter and Shannon Murphy, my two tour guides, used basters to remove dead eggs and to catch hatched fish to transfer to the next tank over.

These Citico Darter eggs, laid on the underside of the pictured rock, were collected in the wild and brought to the facility to grow the fish out safely.

The equipment itself wasn’t without personality or too “factory” looking—in fact, the biologists use toothbrushes to clean tanks and stack floor tiles in tanks to replicate breeding habitats for fish, and semi-organized wads of green yarn (created by the local girl scout troupe!) floated at the top of larger tanks to recreate underwater vegetation. The team is incredibly resourceful, thoughtful, and as they’re among the only ones really doing this type of work, oftentimes having to make things up as they go.

In order to correctly mimic the habitats and breeding conditions of each species, Shannon and Bo explain, they need to spend time observing these fish in their natural conditions. It’s vital to their operations for the team to spend plenty of time with their face in the water, watching each species under their care go about their daily lives in the wild.

After several observations and forming strategies for tank care, the biologists conduct tests to recreate habitat and conditions correctly, oftentimes encountering many unforeseen hurdles. Ingeniously, they occasionally use similar, less vulnerable surrogate species that are biologically similar to the target vulnerable species to get conditions correct. This will allow for less failures when failures, no matter how small, are detrimental to a species.

The biologists often must experiment with water temperature, food intake, and other factors in order to propagate species that have yet to be widely studied.

The founders of CFI, Pat Rakes and J.R. Shute, were really the perfect pair to take on the challenge of fish conservation, as they were both ichthyologists and aquarists, a combination certainly well-suited for the propagation of vulnerable fish species. The founders began their journey as two college students raising the endangered Smoky Madtoms and Yellowfin Madtoms in a handful of tanks on the University of Tennessee campus, and a perfect storm of passion and pursuit snowballed into the success that CFI is today.

The southeast United States is home to an astonishing diversity of water species. According to the Center for Biological Diversity, the southeast harbors “493 fishes (62 percent of U.S. fish species), at least 269 mussels (91 percent of U.S. mussel species)…more than two-thirds of North America’s species and subspecies of crayfish and more amphibians and aquatic reptiles than any other region. All things considered, it has the richest aquatic fauna of any temperate area in the world, rivaling the tropics.”

Tennessee, specifically, boasts seven of the eight most ecologically rich rivers in North America and is the number one ranking state for freshwater fish diversity, making it the perfect place for CFI to plant their flag.

A Tennessee Dace in its spawning stage. Photography by Evan Poellinger.

Shannon, my guide for the day, and Evan Poellinger, another conservation biologist for CFI, wanted to show me a bit of the diversity that existed in my own state of Tennessee, right under my nose. After the hatchery tour, we geared up with wetsuits and snorkels from the shed outside, grabbed a quick lunch, and headed to a stream in the mountains where a week earlier Evan had released a juvenile batch of Blotchside Logperch Darters that the team had propagated in the facility. We were to snorkel the area to see if we could spot any and report back whether the Blotchsides appeared to be acclimating to their new environment.

With a snorkel in hand and wetsuit on, I waded alongside Shannon and Evan to a spot just above a small waterfall to see what species we could spot. We immediately spotted several Redline Darters, tiny and colorful fish taking quick bursts from rock to rock, though they didn’t seem too fussed with us. The three of us floated about, our faces submerged, taking witness to the underwater happenings of the world around us, pointing out fish, crayfish, and snails nestled and hidden in the rocks and fauna of the stream.

A female Blotchside Logperch Darter; the very kind we were searching for in the river that day. Photography by Derek Wheaton

Evan, humble though he was, is I suspect one of the best at identifying fish species in the region; he quickly and accurately identified fish to Shannon and I, patiently and enthusiastically showing us key identifiers of each species, like the hourglass on the tail of the common Redline or the brightly glowing spots on the dorsal fins of the endangered Citico Darters. In just a few short hours, we identified 21 different species.

I’d walked waters like this stream plenty of times before, unaware of the rich and teeming world underneath my feet. I looked for bugs under rocks to know what was hatching and what to throw, sure, but really my focus was looking for water where I suspected trout fed and lounged underneath.

Where we were snorkeling, I would have never guessed such deep pools existed under the surface—in fact; one particular pool harbored a school of 15 or so rainbow trout, all well over 12 inches. We floated among and above the trout, a sight both mesmerizing and tortuous for a bit of an obsessive angler. I could see them feed, hover, and interact with each other in their natural world. Under the adrenaline of enthusiasm, I think I may have even told Evan that snorkeling freshwater streams was better than fishing.

Shannon and Evan snorkel the creek looking for fish.

And again, I thought: how is it that I know nothing about the hundreds of other species in the waters, all deserving of attention and care, just like the trout.

These fish’s allies didn’t have much weight in the ring in the fight for protection until the Endangered Species Act was passed in 1973—an act that has single-handedly help keep 99% of animals on the endangered species from going extinct, according to the World Wildlife Fund. The act ensures that the government and corporations must work with biologists to ensure that measures are in place to keep vulnerable populations from decreasing.

However, there are a few allowed exemptions from the ESA, as proven by the famous case of the endangered Snail Darter found in the Little Tennessee River in 1973, just months after the Endangered Species Act was passed. This was the first time to prove the act’s effectiveness in the court of law—it was created for situations exactly as such. Biologist Dr. David Etnier determined that the building of the Tellico Dam on the Little Tennessee River would effectively cause the extinction of the Snail Darter. Law suits quickly issued by the National Environmental Policy Act slowed construction of the dam but didn’t stop it; as the lawyers fought tooth and nail and the case rose through the courts, the Snail Darter represented more than just itself—it represented the importance of preservation for all species, no matter how small.

Five years later, the dam completed but not yet allowed to begin operations due to the ongoing law suit, an amendment backed by two Tennessee legislators was passed; the amendment allowed for exemptions to the ESA. To determine an exemption to the Endangered Species Act, a committee of Cabinet members and a member of the state legislation would determine whether a project is deemed more beneficial than the continued existence of a species. This committee of legal representatives are nicknamed “The God Committee” because these people, in effect, wield the power of God when making a decision that would wipe a species out to extinction.

The next year, in 1979, the Tellico Dam was granted such exemption. Much to the frustration of biologists, it was allowed to begin operations. It is only thanks to other hatcheries like Conservation Fisheries that the snail darter lives on today despite the death sentence delivered by “The God Committee” forty-three years ago. In fact, because of the attention and care for this fish, it will be officially delisted as an endangered species this September.

Certainly, it’s not my place to speculate, but I do muse and wonder if another, more popular species had been in serious danger from the dam, would the outcome have been different?

Co-founder Pat Rakes collects a darter nest rock from a nearby stream.

Conservation Fisheries is a champion for those forgotten little fish without a voice; the work they do is so crucial to our country’s wildlife. As urban cities continue to sprawl and creeks and streams continue to disappear, we desperately need someone dedicated to fighting on behalf of the victims of habitat loss, deforestation, mining, and invasive species.

Today’s operating stats for CFI are astounding. In the hatchery today, there are: nineteen fish species, 11,057 fish, 850 fish tanks, 20,000 gallons of water, and thirty-three recirculating systems.

And it’s not enough. CFI greatly needs to expand if they’re going to continue making a dent in their efforts—restoration of most species takes years, decades. They’ll need an entire room just to raise their own supply of blackworms, an important staple in their fish’s diet that’s becoming increasingly more difficult to get. They’ve begun plans for construction, keeping hopes for their future high.

We at Mossy Oak hope that by adding our spotlight to a growing list of others highlighting the hatchery’s work, the nonprofit will receive the praise and resources due for their continued hard work and bring the public’s attention to the small fish making homes in the rapidly diminishing waters around the country.

To learn more about CFI’s work and how to donate, visit conservationfisheries.org.