Greg Tinsley

To sustain an environment suitable for man we must fight on a thousand battlegrounds. Despite all of our wealth and knowledge, we cannot create a redwood forest, or a wild or a gleaming seashore. But we can keep those we have. – Lyndon Baines Johnson, 36th President of the United States

In the summer following the American Civil War, Gifford Pinchot (pin-show) was born in Simsbury, Connecticut. One measure of his lineage, a patriarch, had emigrated from France to Pennsylvania in 1816.

The Pinchot family had acquired generational wealth and political influence – to include Congressional family members and friendships with top-ranking Union generals and foreign diplomats – before the lanky and largely home-schooled Pinchot packed for his freshman year at Yale University in 1885.

At Yale the young Pinchot played football, volunteered at the YMCA and, with great encouragement from his conservation-minded parents, James and Mary, he was one of the very first students on American soil to study the management of America’s forests.

After graduation, Pinchot took those forest-supervision studies abroad. Dietrich Brandis and Wilhelm P.D. Schlich, Europe’s leading foresters, became friends and mentors, recommending a graduate tour for Pinchot at the prestigious French National School of Forestry in Nancy.

He returned stateside to a fast-track professional career courtesy of George W. Vanderbilt II, who named Pinchot the forestry manager of Vandy’s Biltmore Estates in Ashville, North Carolina. At Biltmore, Pinchot added to his list of acquaintances, not the least of whom was the iconic naturalist and preservationist John Muir, founder of the Sierra Club, who quickly became another Pinchot confidant and, later, a competing force.

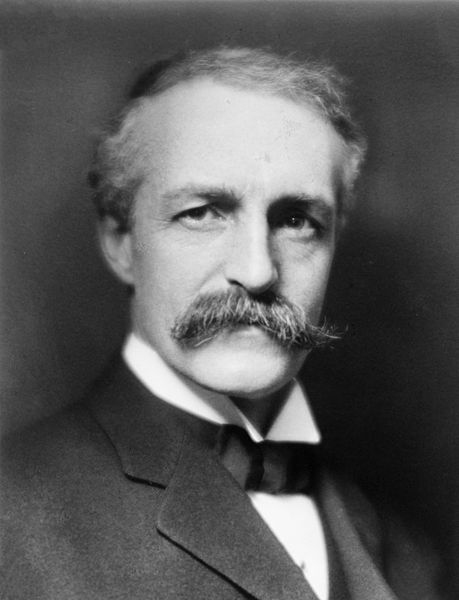

Pictured: Gifford Pinchot

Pinchot left the Biltmore in 1895 to open a private consulting office in New York City. He accepted an invitation the next year to tour the American West with the National Forest Commission. He was not agreeable to the Commission's final report, which advocated zero commercial utilization of the nation’s forests. Pinchot favored the development of a professional forestry service to preside over limited amounts of mom-and-pop commercial activities in America’s public reserves.

In 1897, Pinchot received an appointment to become a special forest agent for the United States Department of the terior. One year later, President William McKinley tapped him to lead the Division of Forestry under the United States Department of Agriculture. that latter post he re-built, filled-in and streamlined the bureaucracy of forest management, while advocating for the science-based renewable-uses of American forests for maximum benefit to humankind. He believed that well-restrained private commercialism of public forests was the only way forward.

He also created an alliance with his colleagues at the Department of the Interior, which technically controlled the national forest reserves. At some point during such professional growth Pinchot coined the term “conservation ethic.”

All or part of this man’s views and works concerning conservation in America were notably contradicted by a host of the day’s leading politicos, industry titans and natural resource experts. This Progressive-Republican was not, however, alone in his conservation ethos, nor would he eventually walk without a Big Stick.

To raise visibility and credibility for the professional sciences of forest management, Pinchot launched the Society of American Foresters in 1905. It was a remarkable year for him to include his nomination as first chief of the United States Forest Service (USFS), which had been established through his influences, and those of his close friend, President Theodore Roosevelt.

By that point, Pinchot and Roosevelt were confidants with a shared vision on how forests and wildlife should be managed for the generational benefit of all. While many others contributed mightily at these earliest flashpoints of the American conservation movement, Pinchot and Roosevelt – as a dynamo of science and politics – are remembered as the nation’s first one-two punch for conservation, a model advocating profitable, plan-renewable use (wise-use) of the nation’s flora and fauna.

Silver, copper, coal, oil – all of the resources from beneath the feet of Americans – would eventually play out, they knew. Managing the critical renewables of clean water and air, wildlife, wetlands and forests was far more important to generational life-on-Earth than the next private goldmine.

Tectonic Conservation, Political Hardball

A handful of notable philosophers and scientists of the Progressive Era also aligned with, and helped shape, Pinchot’s belief that wise-use conservation was mission critical as a vastly important social utility – the noble, national, profit-sharing plan that was best communicated and managed through real science.

However, the preservation of untouched wildernesses was not the pragmatist Pinchot’s greatest concern, as was evidenced by his powerful support for turning Yosemite’s Hetch Hetchy Valley into a gigantic reservoir. Even though wiping out arguably the most exquisite river basin in the universe was (and remains) a soul-crushing event to many – and something far worse to staunch preservationists like the great naturalist John Muir – the damming provided drinking water to tens of millions of American citizens.

Fearless of political crossfires, Pinchot’s new public-land policies, which expanded the roles of federal governance and scientific management, drew the ire of brand-name preservationists, timber barons, mining conglomerates, grifting politicians and ranching empires alike.

In 1907, within sight of what appeared to be the end of Roosevelt’s presidential terms, Congressional opposition to conservation had mounted, the result of which would be a legal remedy to reassert its control of the Forest Service, while prohibiting the president from creating additional reserves. Literally minutes before Roosevelt transferred presidential power to the incoming William Howard Taft, he and Pinchot whistled off a preemptive strike on Congress’s pending legislation, locking up what became known as the “Midnight Forests,” 16 million new acres of public-forest reserves.

Straightaway, President Taft replaced the conservation-minded Secretary of the Interior, James R. Garfield, who had worked so well with Pinchot and Roosevelt, with a new appointee who promptly approved big, long-disputed coal-mining claims in Alaska. Facing concerns and questions regarding claim fraud, the environmental impact of strip mining Alaska’s pristine reaches and the new Interior man’s inferior commitment to conservation, Pinchot very publically pulled out all the stops to block the mining – and in early 1910, Taft was obliged to dismiss Pinchot as the head of the United States Forest Service.

Later that same year, Pinchot helped establish the Progressive Party – a split of the Republican Party – and the Progressives nominated former President Roosevelt for a second full term as Chief Executive. But the Bull Moose and the Progressives could not complete such an improbable comeback. Democrat Woodrow Wilson and a unified Democrat Party defeated both he and Taft in the United States Presidential Election of 1912.

Naturally, the Progressive Party collapsed after Roosevelt refused a presidential run in 1916. Pinchot moved on politically, rejoining the Republican Party, where he would catch a second wind as a public servant.

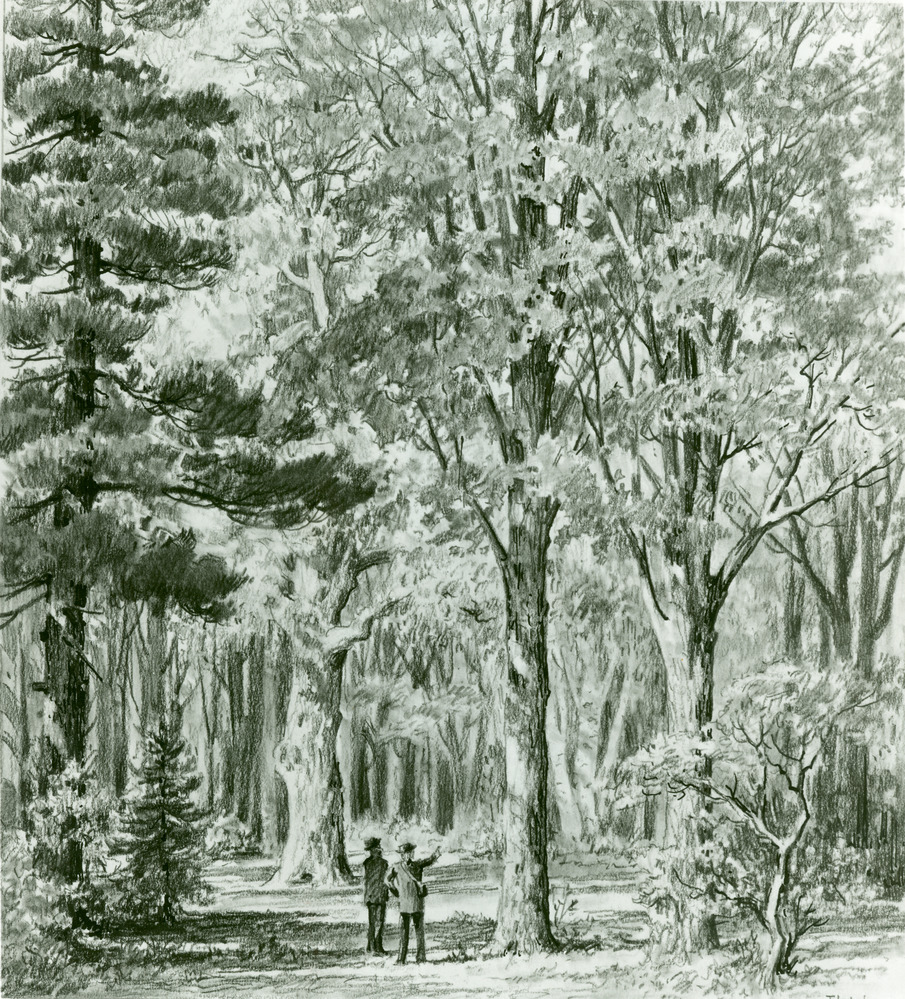

Roosevelt and Pinchot.

Pinchot for Governor

America’s Great Forester returned to office in 1920 as the head of the Pennsylvania forestry division under Governor William C. Sproul. Pinchot promptly cajoled a significant budget increase from the legislature, decentralized the commission's administration and replaced numerous political appointees with professional foresters.

Pinchot succeeded Sproul as Governor two years later. Afterwards, he won a state senate seat before again reclaiming the Governorship in 1930.

First-term Governor Pinchot inherited a $32 million deficit and left office with a $6.7 million surplus. He pursued additional controls on Pennsylvania's electric power industry, but those efforts were defeated by the state legislature.

Governor Pinchot’s second term straddled the worst of the Great Depression. He dutifully avoided overspending, while helping the impoverished and the unemployed. He assisted in the expansion of state parks, led the establishment of 113 encampments for the Civilian Conservation Corps (second only to California) and presided over a rural-road paving operation for farmers and unemployed workers that became known as the Pinchot Roads.

Witness to a Wasteland

Back in 1904, at the height of his federal powers, Pinchot had selected Yale-graduate William Greely to oversee USFS Region I, with responsibilities to 22 National Forests and more than 41 million acres. By 1920 Greely had been promoted to chief of the USFS, a position he would abandon in 1928 to become a Big-Desk executive with Big Timber.

Pinchot and Henry S. Graves toured the American West in 1937 for a look at how the forests had weathered under Greely’s management style. Graves had immediately succeeded Pinchot as the head of the USFS in 1910, which he steered to great effect for a decade.

Out West, the horrors of chainsaw deforestation and multi-ton logging trucks gutted them.

Time Magazine's feature of Pinchot.

Utilizing government-built forest roads, regulatory capture and modern equipment, industrial clearcutting had displayed itself as a forest-eating monster of the New World. Entire mountains and, in fact, complete ranges, lay in one phase of deforestation or another.

“So this,” a brokenhearted Pinchot entered into his diary, “is what saving the trees was all about. Absolute devastation. [In the State of Washington and Oregon] The Forest Service should absolutely declare against clearcutting as a defensive measure."

The teachings of Pinchot and Roosevelt, that wise-use timber and timberlands were best renewed by science-based, family-scale operators, had rapidly been sold down the river.

Pinchot remained active in the conservation movement until his death in October 1946. Shortly before his passing, he petitioned the United Nations to add conservation to its mission, which it would finally recognize during its 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment.

Pinchot’s wife of 32 years, Cornelia Bryce Pinchot, a women’s suffrage activist, was a political firebrand and public-service provider in her own right.

Pinchot’s scientific writings on forestry, his books To the South Seas and Breaking New Ground, his autobiography, became classics. Together with a long line of male heirs, national and state forests, well-traveled canyon trails, mountains and passes, ancient trees, halls of education, institutes of conservation and at least one reptile – the Caribbean lizard (Anolis pinchoti) – Gifford Pinchot and American conservation remain synonymous among students of this all-important movement.

President John F. Kennedy, on behalf of the United States Forest Service, accepted the Grey Towers National Historic Site in Pike Country, Pennsylvania as a gift from the Gifford Pinchot family in 1963. Grey Towers, formerly the Pinchot’s summer retreat, remains the only National Historic Landmark operated by that federal agency.