Greg Tinsley

Now so very long ago, I experienced a banner afternoon with a superb friend at Pete’s Lake in the Wind River Mountains west of Lander, Wyoming.

To arrive at Pete’s one must endure the bad-stony, near-vertical ascent of a Jeep track that fades to a game trail. Eventually, long afoot and sweat-soaked, we found ourselves braced against a glacial headwind at Pete’s unforgettable shoreline. The howling gale soon slackened and the lake unexpectedly fell dead slick, like something redemptive from a psalm.

Materially and topographically, the pure granite Winds are as rough as they come in North America. To lessen the grizzly worry of trekking in there now requires an industrial-grade bear spray in one hand and a .44 Magnum in the other. But the only thing that got mauled on that magical afternoon at Pete’s was butter-belly brook trout. A seemingly endless supply of thick, black-backed clones of more than two pounds each. We quit wondering at the breaking points of our rods only when wide columns of sunray began to spoke outwards through the western twilight, a revelation that framed the +12,000-foot slick-toothed country of Mitchell’s Peak.

I cannot begin to describe the sketchiness of reversing the truck out of there during the earliest moments of our motorized descent. Once released from the anxiety of such dangerous maneuvering, mi compadre began sermonizing about a mountaineer, fisherman, hunter and world-class conservationist named Finis Mitchell. The man who’d been called to deliver the fish to Pete’s.

Pronounced “fine-us,” young Mitchell and his dad, Henry, stocked some 2.5 million trout across a 3,500-square-mile swath of Wind River backcountry dappled with thousands of fish-barren snowmelt lakes.

The fingerlings were salmonids of many flavors that had been incubated at the hatchery in the “nearby” town of Daniel, courtesy of the Wyoming Game and Fish Commission.

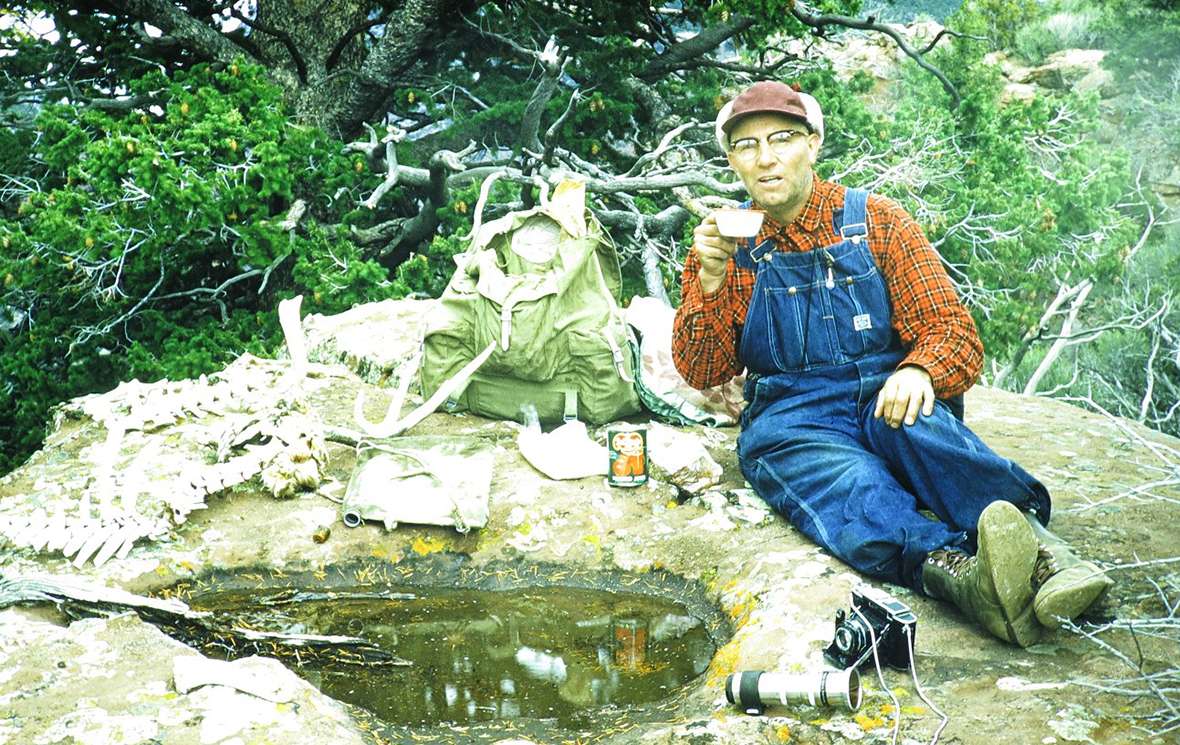

Photography of Finis Mitchell from the Wyoming State Historical Society American Heritage Center and Mitchell's family.

Much of the Mitchell’s equity was sweat, know-how and personal coin. They transported the fish in milk cans topped with burlap closures lashed to pack mules. The Great Depression was on, and like the songs, the Mitchells were probably too financially compromised to notice. Originally from Missouri, they had been quick to become Rocky Mountain survival specialists.

In June of 1930, Finis bought a tent to share with his wife, Emma, and he borrowed pack stock and saddlery to open Mitchell’s Fishing Camp in the Big Sandy Openings on Mud Lake. Their guiding services were free. The Mitchells cash flowed by renting out rented horses to fishermen, and through the sale of Emma’s 50-cent meals. Finis once remarked that he could live indefinitely in the Rocky Mountain wilds on the strength of Emma’s famous fruitcakes.

During the better part of that next decade, by his accounting, Finis and company hand poured fish into 315 remote mountain lakes.

The United States Geological Survey suspended its policy against naming landforms for living persons in 1973 and christened a peak in the southern Wind Rivers near the Cirque of the Towers in honor of Mitchell and his family. A bronze plaque on the trail up there commemorates his 11 ascents. Thereafter, he climbed to the top of Mitchell’s Peak an additional seven times.

Emma and Finis with first generation brook trout from the Wind River Mountains.

His 142-page book, Wind River Trails: A Hiking and Fishing Guide, was published in 1975. It remains a sturdy pocket-size manual, replete with his hand-drawn mapping and his painstaking black-and-white photography, detailing 50 prominent outings. The prose is straightforward and fun. Once the trail disappears on the Mill Creek route to Faler Lake and Bear Lake, he wrote: “You can’t go anywhere but the right place because you’re surrounded by thousand foot ledges.”

Finis was presenting slide shows to local groups in promotion of the Wind Rivers – and for the need to conserve – by the early 1940s. He continued to promote both ideas to local, regional and national audiences for more than 40 years, and he happily sat for interviews by many of the day’s most influential international publications.

In July 1977, the University of Wyoming awarded Finis an honorary Doctor of Laws degree for outstanding service in environmental awareness and conservation.

In March 1980, he presented to the Sierra Club at the Chicago Academy of Science. An advertisement for that gathering noted that he would also discuss the scandalous way America’s public lands were managed. Later in the ‘80s, he led the last of his organized hiking expeditions, still hardly slowed by the exposures of cold wind, icy rock, Father Time and a few of his most serious mountaineering injuries.

He finally finished off one of his legs on a glacier crevasse in 1985 – at the age of 85. That wound, which eventually resulted in amputation, conspired with other health issues to close him out of the Wind River backcountry. And he passed at a Green River nursing home on November 13, 1995, the day before his 94thbirthday.

The Wind River Mountain Festival held each July in Pinedale commonly features a certified Finis Mitchell impersonator. Really? Why on Earth?

Because conservationist Finis Mitchell is a one-of-a-kind American legend.