Greg Tinsley

Near the end of a life well lived, R. Wayne Bailey was often referenced as “the godfather of modern wild turkey management” and/or “the dean of turkey hunters.”

Like all catchphrases of the greats, these were not self-anointments. He never was that guy. Bailey as Godfather and Dean were earned truths bestowed by an adoring and knowledgeable legion of wild-turkey fanatics. Born in Rock, West Virginia in 1918, Bailey would pioneer wild turkey restoration in America, with personal emphasis to the state of his birth and North Carolina. He was the first recipient of the Conservationist of the Year Award by the National Wild Turkey Federation in 1978, the organization he’d co-founded five years earlier.

Eastern wild turkeys were wobbling along the limb of extinction when Bailey rolled up his sleeves as a state biologist in 1945. Situation: dire – widely scattered remnant populations in decline. And the emergency protocol for that was to rebuild turkey flocks to suitable habitats at Godspeed. A tricky, primitive, excruciatingly slow live-trap solution when Bailey first came to attack it with homemade drop nets and walk-in wire traps, apparatuses he relied on until word reached him about the advent of the net cannon.

This American Boom Trap breakthrough was developed by biologists Herbert Dill and William Thornsberry. Electronically triggered from as far as 400 yards away from baited capture sites, these gizmos used mortars to fire cast nets over wildlife, harmlessly entangling even delicate animals like birds. Dill and Thornsberry first went live with the method in 1948, capturing 32 wild geese at the Swan Lake National Wildlife Refuge near Sumner, Missouri.

While the net cannon for wild animals remains a completely tedious affair, it was a technological boom for the early grinders of Bailey’s skill- and mindsets. With increasing numbers of young professionals eager to work with a man who was on track to become one of America’s preeminent field biologists, Bailey and crew became the first state-sanctioned exporters of wild turkeys, with shipments to Ohio, Illinois, Massachusetts and New Hampshire. His effective efforts on turkeys and their habitats also influenced wildlife managers in Vermont and Pennsylvania.

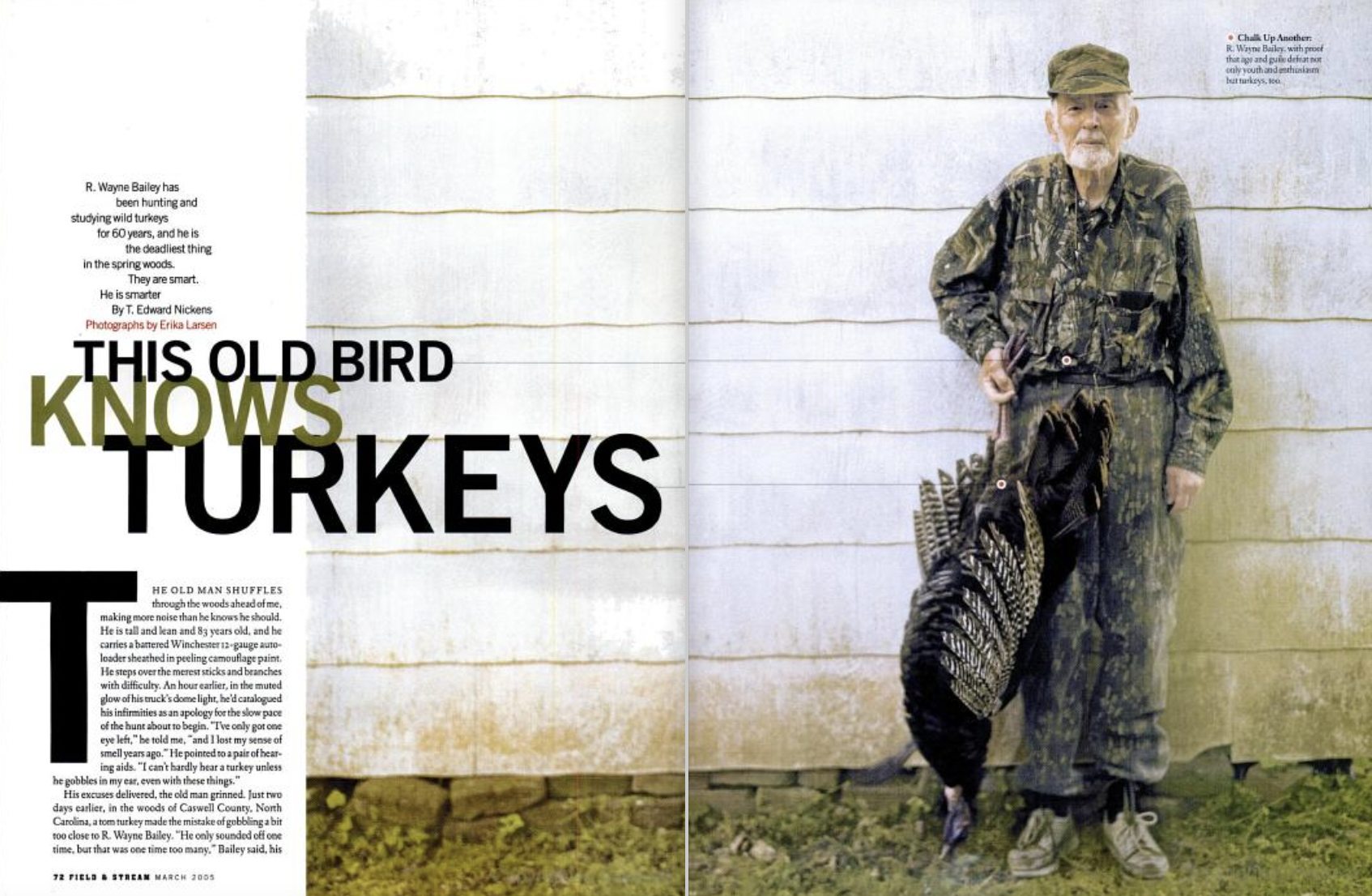

“As I sat in the trap blinds, listening to a gobble, or even a movement in the leaves that I knew was a turkey, my heart would pound so loud you could hear it,” Bailey told author T. Edward Nickens, writing for Field & Stream magazine in 2005.

“First and foremost, Wayne was more responsible for the restoration of the wild turkey in our nation than any other biologist,” said Jim Pack, former turkey biologist for the state of West Virginia. “He initiated and supported the first spring gobbler hunting seasons in West Virginia and North Carolina, which now provide millions of hours of recreation each year to the citizens of those states.”

“It is kind of sad that we have a whole generation of turkey hunters who have never heard of Wayne Bailey,” said Curtis Taylor, former wildlife section chief for West Virginia. “But I knew him just a little and I don’t think he would mind. Wayne Bailey was an old-school git’er- done biologist. He was in the job because he loved turkeys and turkey hunting, not for any fame associated with it.”

Bailey’s 10-year study on the population dynamics of wild turkeys is the landmark science of that sector. In all, he wrote more than 100 papers and self-published two books advancing the profession of wildlife management, wildlife conservation and turkey hunting. And while he probably would not care if readers remember him as a royal member of the American society of field biologists, he sure might want us to understand, however briefly, that he was an artful hunter and superbly capable killer of wild turkeys.

For that ’05 F&S story, with photography by Erika Larsen, the great writer Nickens was blessed to share a hunt with Bailey, who had collected his 239th wild turkey just earlier in the week. Eventually, as one of two gobbling Easterns quickened to what mattered most, the magnificent old man leaned to Nickens and whispered:

“I think it’s going to be a good morning. It takes a turkey to tell you just how good a morning it’s going to be.”