David Hawkins | Originally published in GameKeepers: Farming for Wildlife Magazine. To subscribe, click here.

hemorrhagic disease such as EHD will have antibodies that she will pass to her

fawns.

GameKeepers, as a rule, are very protective of their property and every creature that roams there. We personify the land and land marks, deer stands and food plots until a conversation includes the likes of “Eber’s Patch,” “The Tree Top Stand,” the “Lower Bottom,” the “Mud Road,” or “Becky’s Ten Point Stand.” Animals are the same; with names such as “Double-Six,” the “Tall Eight,” “Queer Bird” or “Lucifer.” We become so possessive and caring of the wildlife that it becomes something of an extended family. Because of this we get upset when something outside our control comes along to make our critters sick, or causes them to die.

White-tailed deer are susceptible to several diseases and are hosts to numerous parasites. Deer tolerate most of these diseases and parasites well, and in most populations disease-related mortality is limited. Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) is marching across the nation and well measured steps are being taken to monitor and slow the spread of this vicious disease. Epizootic Hemorrhagic Disease (EHD) or bluetongue virus (BTHD) is common in the south and has moved north for the past several decades. Major outbreaks have occurred in Missouri and Michigan over the past 10 years, proving it is not just a disease of deer in the southern climes. If there is a bright side, the infection period is limited to late summer and early fall, and deer mortality may be limited to a few each year. The bad news, and there is ample, is that the virus mutates and new strains are being discovered. In fact, EHD and BHD are different strains, or serotypes, of hemorrhagic disease, but for clarity, this article shall treat them as one in the same.

In southern states, where deer herds have been infected and exposed for many years, the mortality rates typically are less than 15% annually. Over time infected deer produce antibodies to the virus. These antibodies are believed to be passed from doe to fawn. In northern deer, higher rates of mortality exist because herds have not been exposed and lack a strong antibody level. Simply said, as deer get the disease, those surviving until another outbreak stand a better chance of surviving another outbreak. Harvested deer that have survived EHD may exhibit hoof sloughing that can lead to foot injuries. Most deer harvest data reports allow hunters to report this malady along with deer weight and other information.

In a MSU Deer Lab study, deer with northern origins were 2-3 times more susceptible to EHD than deer of southern origin. This virus has been causing particularly significant outbreaks recently in the central U.S. For example, the Michigan DNR reported record mortality during the summer of 2012, according to Mississippi State University Deer Researcher Dr. Bronson Strickland. Epizootic hemorrhagic disease typically hits during late summer and fall and coincides with peak populations of biting midges that serve as the vector,” Strickland said. “This disease is the prime suspect when dead or dying deer are found around water holes during late summer or fall.”

Deer infected with EHD exhibit a number of behavioral signs that allow landowners to judge the cause of the malady. The life of the virus is 7-10 days on average. Loss of fear of humans is one of the symptoms, as is a desire to be in or near water. An infected animal suffers from a high fever. The deer, elk or moose is then attracted to water in an attempt to cool off. Difficulty breathing, swelling of the head, neck and tongue, lameness and weight loss can also be signs. It is much like a human having a bad cold, or influenza. Hemorrhagic disease is not directly contagious between infected animals, and humans cannot contract the disease from deer. The meat of an infected animal is safe for human consumption. “We see and treat the HD viruses in cattle and sheep,” said Dr. Mike Walker, a veterinarian, land manager and deer hunter from Mississippi. “Domestic livestock exhibit some different symptoms from those of wildlife, but cattle can be rounded up and vaccinated whereas deer are near impossible to treat.” As dire as the HD viruses sound and as dramatic as some of the die offs have been, preventing outbreaks, or at least lessening the mortality, is not out of the question.

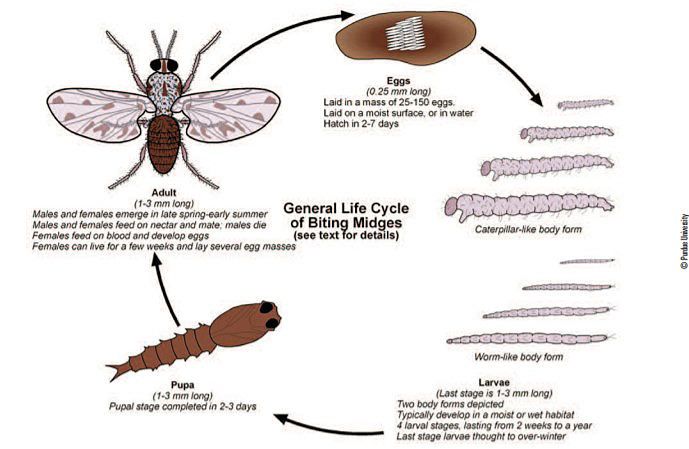

There are things gamekeepers can do in every climate. But to understand those actions one must first understand how the HD viruses work, from transmission to infection. Also understand, there is no magic bullet, no panacea treatment, and the HD diseases will not be eliminated, based on what is known by science at the current time. EHD typically hits during late summer and fall coinciding with the peak populations of biting midges that serve as the vector (an insect that carries germs that cause disease). HD is the prime suspect when dead deer or dying deer are found around waterholes during late summer and fall. A frost will kill the midges and pretty much end the cycle for the season. The midges, also called gnats or no-see-ums are of the genus Culicoides, of which there are several known to transmit EHD. These are the same tiny blood-sucking creatures that are a bane to humans who work and play in the forests and fields in later summer.

It is the life-cycle of the midge that offers a gamekeeper an opportunity at a chance to fight back. Key to the midge’s existence is the presence of a mud substrate. One biologist said a stock pond was the ideal setting for midge reproduction. Living in the shallowest water where oxygen is scarce, midge larva has few predators. Once the larva matures into the flying form, only the female becomes the blood sucker. Removing the breeding site will lessen the chances for midge infestation. When constructing a wildlife watering hole or refurbishing one, consider the water depth at the edges. Keep the edges as steep and deep as practical. This will lessen the amount of area the midge has to breed. Keeping the water quality high will encourage shallow feeding fry, crawfish, tadpoles and the like to pick off the midges as they emerge from the mud to become the fly form. Simply put, the healthier the water and the less mud exposed, the better the conditions for deer. Well drained property is another safeguard. Land managers can identify those areas where water stands during the rainy periods such as in the spring. If the water does not evaporate rapidly, or fails to soak into the soil, consider ditching or surface modifications that will stop the standing water problem. Logging activities often create skidder ruts that will hold water for much of the year. Such locations are usually rich in organic material and are a breeding place for midges and mosquitoes.

Using a larvacide is an iffy proposition at best. While some chemical applications might kill some insect larva, midge larva is resistant to salts such as those found in cattle feedlots and runoff. If the application doesn’t target the specific midge, it could actually be beneficial to them by removing competition. So what else is a gamekeeper to do to lessen the outbreaks of EHD and BHD. Actually there is quite a bit. It begins with the knowledge of HD viruses; when and how the viruses attack deer or other ruminants such as elk, moose, or sometimes pronghorns. Be observant – inspect waterholes and creek banks in late summer and fall for dead or dying deer. The presence of buzzards or sightings of eagles or coyotes should be investigated. When a fresh deer is found, contact a conservation officer and request that a sample of blood or tissue be taken to send to the Southeast Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study at the University of Georgia. The SCWDS tests samples from sick deer in a number of states. Be conscious of your land’s carrying capacity. High concentrations of deer lead to weaker animals stressed by nutritional and sometimes social demands. Remember, the environment during late summer and early fall during a drought year is taxing deer at the same time it is benefiting midge production. Remove older does, those that have passed reproduction age, early in the bow season. Those early seasons generally take place before the first frost.

Mitch Banks, of Banks Outdoors, claims his product, the Wild Water Watering System provides clean water with little or no evaporation, allowing strategic placement with no mud, thus eliminating the midge problem. “We are selling a lot of 100-gallon units in Kansas, Missouri and throughout the Midwest,” Banks said. “We are currently developing larger tanks because some landowners are saying the animals are empting the units too quickly.”

A farmer with a shallow well and a windmill could create the same principle and let the ever-present wind pump the clean water into a trough. Any idea that limits the presence of mud to prevent the midge from reproducing is worth investigating. Lastly, with supplemental feeding being so popular, never place a feeder near a water source that will foster the cycle of midges. Anything that causes the unnatural concentration of deer near mud needs to be removed. Midges are weak fliers, so their misery does not travel far from their home. Hemorrhagic disease is present over most of the whitetails’ range. Unlike Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) which is usually a death sentence, EHD is not. Gamekeepers have a chance, and thus an obligation to manage the resources for the best possible results.

Information for this article was provided by:

Mississippi State University Deer Lab; Michigan Department of Natural Resources; Missouri Department of Wildlife; Southeast Cooperative Wildlife Disease Study. For additional resource information visit: www.msudeer.msstate.edu/; www.michigan.gov/dnr; www.mdc.mo.gov/wildlife; www.banksoutdoors.com.