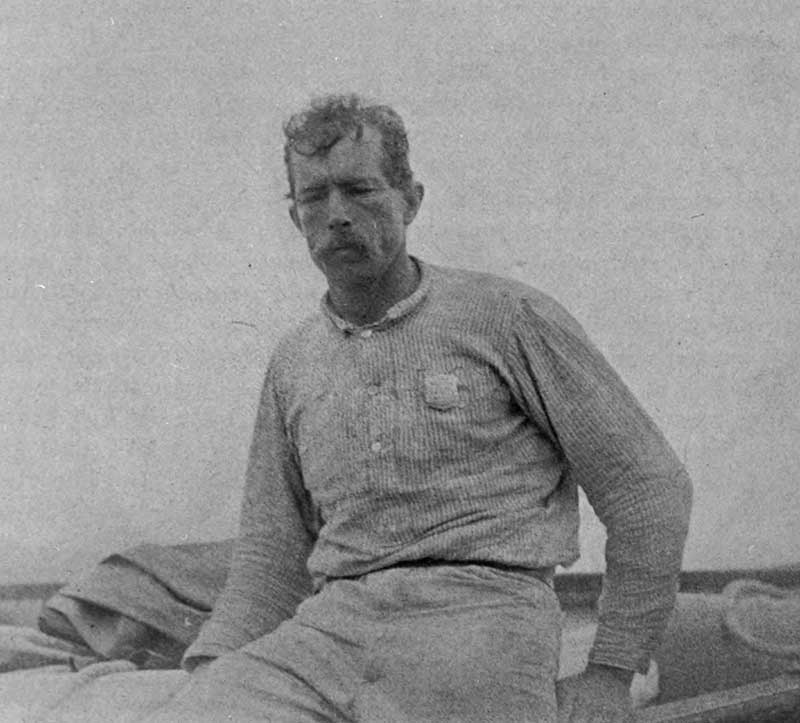

Greg Tinsley

Initially from Chicago, Guy Morrell Bradley settled with his parents in Flamingo, Florida, at the southern extreme of the Everglades, soon after postal service was established to that far-flung coastline.

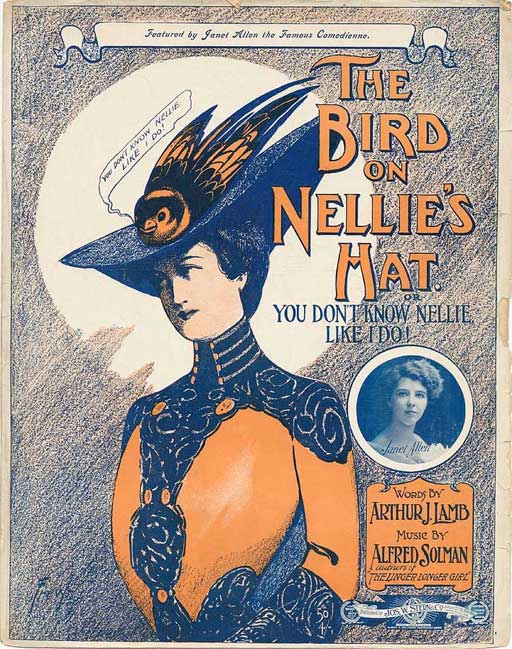

By age 15, Bradley, his older brother Louis, and their friend Charlie Pierce, had sailed with Jean Chevalier, a notable French plume-bird tradesman during the Parisian’s Everglades expedition of 1885. The small company advanced to Key West on Pierce's sloop, the Bonton, destroying 1,397 birds of 36 species for their plumages – feathered skins destined for the finest millinery shops of the world.

Demand by hat makers for the hides of elegant birds increased into the 1870s, and by 1886 some 5 million of these spectacular avians were used annually by the fashionista. With eggs and blinking chicks abandoned to rot in the tropical sun, the supply side of the business featured a grotesqueness all its own.

The Lacey Act became law in 1900, federally criminalizing at least one of Guy Bradley’s earlier transgressions. That notwithstanding, the American Ornithologists' Union (AOU), at the request of the Florida Audubon Society, hired Bradley in 1903 to pinch the wholesale slaughter of south Florida plume birds. The bird-protection model of the AOU had recently become Florida law.

Pleasant, quiet, blue-eyed, always whistling and a pretty good violinist is how Bradley was described by his interviewer. A social asset to the isolated, frontier community, clean-cut, reliable, courageous, energetic and conscientious.

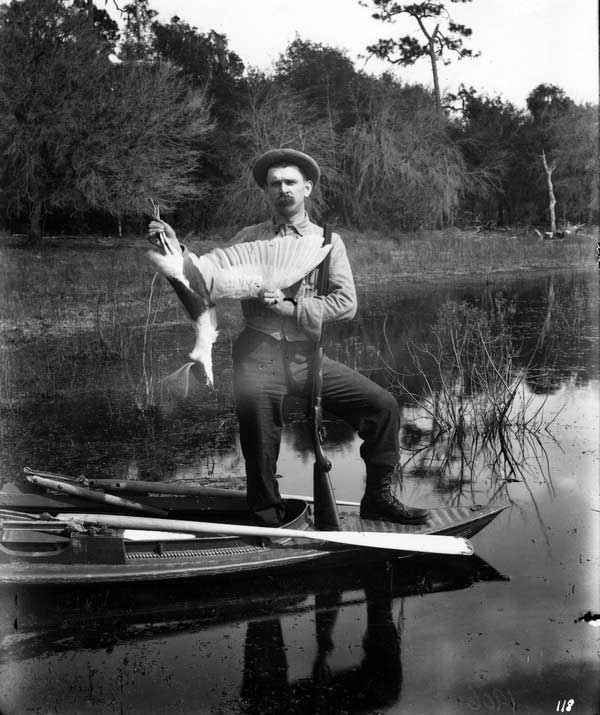

Bradley earned a monthly $35 stipend at his new job, which primarily had him in command of solo sailboat operations from Florida’s Ten Thousand Islands to Key West, an enormous arc of formidable wilderness that nested valuable plume birds like egrets, herons, spoonbills and ibis.

With aigrette crowns fetching $32 per ounce, the market price for plumes competed with pure gold.

JOHN W. WEEKS: CONSERVATION LEGEND, 20 MILLION ACRE MAN

In essence, the repentant Bradley invented America’s public-servant version of the noble game warden. He spoke widely to the value of law-of-the-land conservation, posted signs, created a network of informants and hired assistants. Among mangrove trees decorated with poisonous serpents, he patrolled shark-infested waters that boiled with mosquitos and saltwater crocs. Alone to the fresh silence, the spavined horrors of shot-out rookeries.

And his exploits exposed and unhinged a cartel of hardened crazies.

Bullets flew, houses were set afire, boats were scuttled and psychotic toughs made death threats against him. Considered America’s original game warden, Bradley, by then a young father, was also the first wildlife ranger to be killed in action. On July 8, 1905, he was shot by the notorious plume outlaw Walter Smith, who hauled Bradley back into his boat and set him adrift to die in the Mexican Gulf.

Other game wardens were also soon felled. The body of Columbus McLeod, who worked Florida’s west coast farther north, near Charlotte Harbor, was never found. Authorities did discover his bloodied, split-open hat and his boat, which the murderer(s) had weighted and sunk. The Governor offered $100 for information, a reward as yet unclaimed.

Pressly Reeves, a game warden in the employment of the South Carolina Audubon Society, was murdered in ambush that same year.

The broadly reported assassinations of Bradley, McLeod and Reeves were pressed against the state of New York, and the Audubon Plumage Act of 1910 was passed, outlawing the plume trade. Other states followed, and bird-skin hats were soon federally banned from sea to shining sea.

By the time dentist, best-selling author and fishing adventurer Pearl Zane Grey turned his scow up a meandering Everglades creek near Cape Sable, just a few years later, the birds and their rookeries were enjoying a strong recovery. Overlooking Florida Bay, in spirit and in earthly remains, Bradley (1870-1905) was most certainly right there, too.

In recognition of the accomplishments of the country’s most outstanding state and federal wildlife patrol officers, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation established the annual Guy Bradley Award in 1988.

In the Photos:

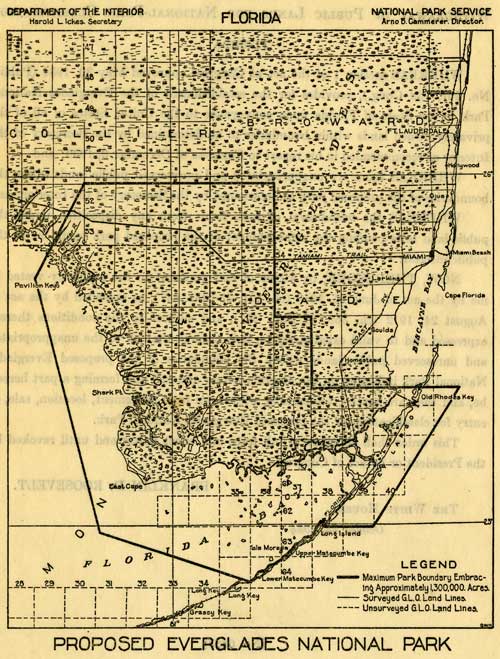

Guy Bradley was the first one riot, one ranger of wildlife protection law. Alone, he patrolled the Florida Everglades, decades before a momentous section of the River of Grass was lifted to National Park status, as shown in this late 1930s-era map from the collection of the State Library and Archives of Florida. His mission was to preserve the region’s birdlife from the market slaughter of the millinery trade. When Bradley pinned on badge #1, crown feathers, like those atop this lifeless black-crowned night heron, were worth their weight in gold to big-city hat makers.