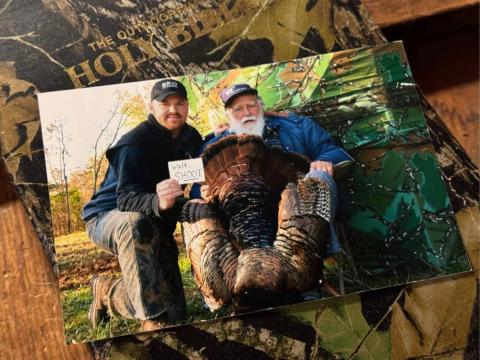

Text and Photography by Tes Randle Jolly

It’s “turkey time,” and the “king of spring” obsession begins. We plot, plan, scout and practice those annoying yelps and hoots at family members like we’re cramming for college finals. Soon our large, grapefruit-sized brain will be pitted against toms with a measly grape-sized wad of gray matter, which during the spring, has all circuits locked on two things…procreation and staying alive. If we’re blessed, there’ll be times our sizable brain functions spectacularly and our tag is punched. There’ll surely be plenty of head-scratching, hat-slamming encounters that prove brain size really doesn’t matter…and that’s a fact!

Following are other facts about wild turkeys you may not know. Good luck in the turkey woods. May your grapefruit-sized brain prevail!

“IT’S ABOUT CREATING A LEGACY FOR ALL FUTURE GENERATIONS. SUBSCRIBE TODAY!”

Turkey History

North America’s wild turkey (meleagris gallopavo), evolved more than 11 million years ago into five subspecies. It has just one close relative, the gaudy-colored oscillated turkey that inhabits Central America, primarily on the Yucatan peninsula. Wild turkeys, especially the tom, with its iridescent feathers, colorful wattles, magical snood and impressive fan were revered in ancient Mayan and Aztec civilizations. Aztecs called them huexolotlin. They, and the Mayans, honored wild turkeys with religious festivals each year using the feathers to decorate clothing, jewelry, headdresses and necklaces. They also recognized the turkey as a valuable food source. Domestication first occurred in Mexico and later tribes such as the Navajos in the American Southwest raised wild turkeys to fatten for food.

Spanish explorers encountered the domesticated birds in Mexico during the 16th century. They were included in the plunder taken back to Spain around 1519 and later exported to England. The European birds were further domesticated and later reintroduced to the New World in the 1660’s where the forests in the Northeast already had wild turkey populations. The ancestor of our modern Thanksgiving turkeys is actually the European-bred but originally Mexican domesticated wild turkey.

Feather Facts

An adult wild turkey is covered with 5 to 6 thousand feathers in various sizes, shapes and colors that lay in patterns called “feather tracts.” There are eight different feather shapes. The shaft of a body feather is nearly 3/4s grayish fluffy down. The head, neck and breastbone area are virtually featherless. Older birds develop a callous on the breastbone skin from friction against roost limbs.

The iridescence of the feathers of an adult strutting tom in the sunlight is a remarkable sight. Their feathers shimmer like a mirage in red, gold, copper, green, purple and bronze. The tail fan averages 18 feathers but may be more or less. Feathers serve several survival functions - protection from the elements, camouflage, touch sensation, for flight and ornamentation when attracting the opposite sex. From poult to adulthood, turkeys go through four feather molts.

“IF YOU LOVE WILDLIFE AND WANT TO IMPROVE HABITAT, SUBSCRIBE TODAY!”

The beard is a modified feather of bristly filaments that grows from the breast area. Toms have beards, though about 1 in 10 hens is also bearded. The beard’s function is not known with certainty, however it may influence mate selection by hens. Longer beards indicate healthier, mature males and therefore prime mates.

Snoods

Only the wild turkey and the oscillated turkey have a snood. Savvy turkey hunters are snood watchers. It’s the slinky-like appendage with a life of its own growing from the top of the beak. Colors range from white, gray, shades of blue, pink, red or purple. The snood is a “mood meter” that indicates a turkey’s state of mind. It identifies and/or rates gender, sexual readiness, health and emotions. Male turkeys have larger, more developed snoods, especially during mating season. Some hens lack snoods.

Only the wild turkey and the oscillated turkey have a snood. Savvy turkey hunters are snood watchers. It’s the slinky-like appendage with a life of its own growing from the top of the beak. Colors range from white, gray, shades of blue, pink, red or purple. The snood is a “mood meter” that indicates a turkey’s state of mind. It identifies and/or rates gender, sexual readiness, health and emotions. Male turkeys have larger, more developed snoods, especially during mating season. Some hens lack snoods.

A tom’s snood is long and brilliantly colored during courtship and mating. Studies show hens prefer toms with longer snoods. A long, prominent snood suggests a healthy bird. Studies indicate better bacteria resistance in birds with longer snoods. Bolder colors indicate aggression or mating readiness. Because it is fleshy and blood-filled, it can change length very quickly. A snood that is retracted and pale-colored indicates the bird is frightened. An angry bird has a short, boldly colored snood. A relaxed snood suddenly shortens when a turkey is alarmed or senses danger.

Full Strut - How It Happens

Turkey hunting wouldn’t be near as much fun if turkeys didn’t strut. Do you know how they do it? The mesmerizing transformation that inhabits the dreams of turkey hunters is actually a form of controlled goosebumps. Think “turkeybumps.”

Certified wildlife biologist, Bob Eriksen, explained the mystery. The small muscles located at the base of each feather enable the bird to move and control the position of its feathers. Those muscles are connected to other very small muscles within the skin. When strutting, the turkey contracts the muscles that control feather position, causing the body feathers to stand erect. The same applies for a group of muscles located at the base of the tail, which acts as a swivel to display the fan more effectively. The same muscles in the wings enable the primary wing feathers to drop to the ground.

Turkey Talk

Start to finish, a gobble happens fast, lasting about a second. Interesting things happen in that short space of time that the naked eye can’t see. With high speed, digital frame rates a sequence of one gobble can be shot and analyzed in multiple images. The gobble is actually prefaced with the tom tilting its head downward, the beak opens wide, presumably to gulp air, the head and neck extend and the bird gobbles. During the gobble, the second, or inner eyelid often closes. A droopy snood may get caught like a worm in the bird's beak as it whips about from the force of the gobble.

Ground and Air Speeds

A turkey typically opts to run from perceived threats, ducking its head and tucking low to the ground. No wonder turkey legs take hours to tenderize in a crockpot. Its muscular legs enable sprint speeds up to 15 mph with incredible agility and explosive speed.