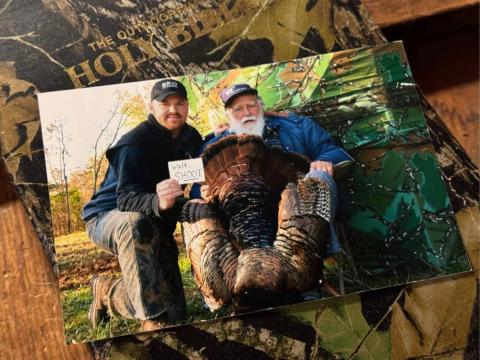

provided by John Phillips

Osceola turkeys are a subspecies of the eastern wild turkey. The Osceola turkey got its name from Chief Osceola of the Seminole Indian nation. Today about 100,000 wary and hard-to-hunt Osceolas live in central and south Florida, primarily south of Orlando. Most Osceolas live on about 20 public Wildlife Management Areas (WMAs) with some on private lands. One of the men who knows the Osceola best is Keith Kelly, the manager of the Dee-Dot Timberlands, 25,000 acres of timberland near Jacksonville, used exclusively for family, friends and charity turkey hunts.

Last season I was hunting in a blind with a wounded warrior in a wheelchair. I gave the turkey on the limb soft calling, clucking, purring and some short, soft yelps to imitate the sound that a hen makes when she flies down. The gobbler answered my call when I gave him those soft calls. I waited a little while, and then I called again. But the gobbler didn’t answer me. What I learned was that just because a gobbler didn’t answer me the second time I called didn’t mean he hadn’t heard me, or that he wasn’t coming near me. That wasn’t unusual when hunting Osceola turkeys.

Next, I heard some hens tree-yelping close to the Osceola. I was fairly certain that when he flew down, some of those hens had flown down with him. The hens were calling right where I’d heard the gobbler. I’d learned that generally when an Osceola pitched out of the tree, if he had hens with him, they’d usually stay fairly close to the tree where they’d roosted and try to decide where they’d go for that day.

As we sat still in the blind, I heard the hens talking and moving toward us, and the tom would gobble every now and then. I didn’t call to that bird more than four or five times, since I knew the hens were coming toward us and dragging the gobbler to us. We also had put a hen decoy out in front of our blind. When hunting in south Florida where the land was so open, most of the time we put out a decoy to give the gobblers and hens something to look at and to reinforce the idea that the hen they heard calling they now could see. The flock drew closer to us and the hens walked right up to the decoy.

This is another reason why I’m a strong proponent of hunting from a blind when you’re hunting in the open ground of south Florida. If a gobbler is with hens, you have so many eyes looking for you that there’s a very good chance they’ll spot you and spook. However, if you have a hen decoy out, and you’re sitting in natural blind, those hens can walk right in front of you and never spot you.

This is another reason why I’m a strong proponent of hunting from a blind when you’re hunting in the open ground of south Florida. If a gobbler is with hens, you have so many eyes looking for you that there’s a very good chance they’ll spot you and spook. However, if you have a hen decoy out, and you’re sitting in natural blind, those hens can walk right in front of you and never spot you.

Most of the time the gobbler would be following closely behind the flock of hens, and that happened on this hunt. The gobbler walked straight for the decoy. My hunter started getting really excited when he saw all those hens, and even more excited when he spotted the gobbler. Before my hunter saw the hens and the gobblers, he’d whispered, “Are you sure they’re going to come? He hasn’t answered your call.” Like many hunters, this vet thought the turkey should gobble every time I called, but he didn’t. My vet would whisper, “Call to that bird some more to get him to gobble.” I’d tell him, “No. We’re doing good.”

When the gobbler is with the hens, and the hens are coming toward you – that’s exactly what they are supposed to do. If you continue to call, the boss hen may lead the tom away from you because she won’t want him getting with this unknown hen. If you don’t call, the boss hen doesn’t feel threatened by this unknown hen, and she’ll continue to bring the gobbler to you most of the time. Remember, you’re in really open woods, so those turkeys can see a long way. Once they spot that decoy that’s not moving, the boss hen doesn’t have a problem continuing on the path she’s on and bringing the flock and the gobbler with her.

I kept whispering to my hunter, “Just be patient. We’re doing everything right, and if that gobbler wants to come to us, he’ll be here in a little while.”

I’m convinced that patience is the greatest tool a turkey hunter can have. The people with patience usually will harvest more gobblers than the people who don’t. Some turkey hunters are what I call gobbler chasers. They just want to keep that turkey calling - whether they kill him or not - and often they don’t. When I'm hunting Osceola gobblers, I don’t do much loud yelping and cutting. If you listen to the hens when you’re hunting Osceolas, most of the time they talk softly. So, that’s what I do.

One of the advantages that we had on this hunt was I found that when your hunter couldn’t move like my vet in a wheelchair couldn’t, and there were shooting sticks where he could rest his shotgun, if you’d put his shooting sticks and his gun aimed at the decoy, he had to move very little when the gobbler came in, since most of the time the gobbler would go toward the decoy.

On our hunt, when the hens arrived at our blind, they hung around the decoy - clucking and purring. My hunter was breathing heavy, and I was pretty sure his heart was pounding. He already had heard the gobbler three or four times as he came toward us, and he was prepared to see him at any moment. We were able to see the gobbler when he was a little ways out, strutting and drumming as he moved toward us. By this time, my hunter was worked-up and excited. He started whispering, “I got him! I got him! I got him!” He barely could catch his breath.

This was the first time this vet ever had hunted a turkey. He was shooting a 20-gauge, Turkey Thug Mossy Oak shotgun, a semi-automatic covered in Mossy Oak Obsession camo. It had a turkey scope on it, and a turkey choke in it. Using TSS shells, that 20-gauge could kill a gobbler out to about 40 yards, maybe a little more. It had very little or no recoil.

I recommend that anyone who takes a youngster or a novice turkey hunter allow him or her to shoot a 20-gauge, especially with a scope on it. The advantage of having a scope, especially for youngsters and first timers, is that they have to keep their cheeks on the stocks and see the turkeys in their scopes before pulling their triggers. Most people who are not accustomed to shooting a shotgun and looking at the beads on the ends of their barrels will pull their heads up off their stocks when they’re ready to shoot. Then the shotguns will go down, and they’ll miss their turkeys.

When my hunter shot the turkey, he really got excited. I jumped out of the blind and ran to the turkey to make sure he was dead. When I got back to the blind, there was a lot of yelling and hollering, scaring anything else in the woods. But that was okay, because if my hunter wanted to get really excited, I was tickled to death for him. That’s something I love about guiding these hunts – they’re always a fun time for all.