Ron Jolly | Originally published in GameKeepers: Farming for Wildlife Magazine. To subscribe, click here.

Mother Nature is a fickle, ever-changing beast. The day-to-day progression of tree and plant communities is barely discernible, however, year-to-year development is much more obvious. Decade-to-decade, this progression is dramatic and often detrimental to wildlife. Nowhere can this evolvement of habitat be better observed than in planted pines.

Pine plantations are a fact of life in the south. Between the years 1975 and 1997, the federally funded “Forest Incentives Program” and the “Conservation Reserve Program” inspired the planting of nearly 50 million acres of marginal timber and farmland into pines and hardwoods. Today, there are four million acres of trees planted in northern states, 38 million acres in the south and 14 million acres in the west.

Our farm is located in east-central Alabama. Like many farms in Alabama, planted pine plantations occupy a portion of our acreage. 20 years ago, in 1995, my wife Tes and her Dad planted 20 acres of pastureland to pines. The idea was to provide attractive habitat for deer and grow a cash crop at the same time.

By 2001, that original 20 acres had matured to the point of forming a canopy that was having a strangling effect on the natural vegetation which is vital bedding to deer. That year we planted 10 more acres of pines and another 10 acres in 2003. Two decades of managing pine plantations has taught us many things. Perhaps the most important lesson learned is “patience.”

Biological Desert

The first 15 years in the life of a pine plantation are a time of great transition. The first five to eight years produce abundant browse and cover for wildlife. However, after those first years the pendulum swings as the pine seedlings grow in height and width to form a canopy impenetrable by sunlight. This is called “crown closure.”

and pine straw and exposes the mineral soil. Fire

influences ground cover vegetation through

scarification of seed and increases germination.

By the 10th year, most plantations consist of the planted pines and a few hardwood saplings. Practically all growth beneficial to wildlife has disappeared due to lack of sunlight and competition with the pines for nutrients and moisture. Now is the time for the first prescribed fire. This fire does little if anything to encourage new growth beneficial to wildlife. This burn does, however, release nutrients stored in the duff that benefits the pine stand. It is applied to remove the years of accumulated duff, straw and fuel on the ground that could devastate the pines if an “unplanned” fire breaks out. It also will eliminate some of the unwanted shrubs and trees. It will be another five to eight years before your plantation is ready to be thinned.

Time to Thin

If there is one thing we have learned it would be that nothing good happens quickly. It takes time for Mother Nature to do her work. Throughout history man has searched for ways to alter the environment to his advantage. Native Americans used fire for this purpose.

In pine plantations, fire is a very useful tool, but a fire’s most dramatic effect occurs after thinning the stand. It is at this stage you finally have options; options that affect the dollar return on your investment and options that affect the wildlife on your farm. Put simply, you have to decide where your priorities lie.

There are several options when it comes to thinning a pine plantation. If your primary goal is a long-term cash return you should consider thinning by rows. Depending on the size of the trees, some choose to remove every fourth row. Others choose every third row. This is the first cash return on your investment in planting pines. Both of these methods open the canopy and allow sunlight to reach the ground. Both of these options require another thinning eight to 10 years later when the canopy has again closed and shades the ground. The second thinning produces another check.

Our goal was to as quickly as possible create bedding and browse for our deer and nesting habitat for turkeys. To be certain we were on the right track we asked the experts.

Bobby Watkins

Bobby Watkins is a land manager and consultant whose expertise lies in managing pine plantations for natural forage regeneration beneficial to wildlife. My wife Tes and I had attended one of his field days several years before and were impressed with Watkins’ approach. He calls it “Quality Vegetative Management” (QVM).

Our first step was to thin our pines. We used the selective method. This method takes out certain rows but allows the operator to remove inferior trees. Our goal was to reduce our stand to approximately 80 trees per acre. This is called basal area.

“Quality Vegetative Management is a combination of thinning, chemical application and prescribed fire that stimulates the growth of natural biomass and natural forages,” said Watkins.

“Thinning allows sunlight to reach the ground. The more pines you remove, the more sunlight reaches the ground. Chemicals like Arsenal (imazapyre), will remove unwanted trees and shrubs too large for fire to kill. Prescribed fire removes the dense layer of mulch and pine straw and exposes the mineral soil. Fire influences ground cover vegetation through scarification of seed and increases germination.”

“The nutritional carrying capacity for our deer herd increased dramatically in QVM treated areas. We assumed a deer needed three pounds of forage per day (dry weight), and an average diet quality of 12 percent protein. The average nutritional carrying capacity for the QVM treated areas was 109 deer days per acre. Untreated areas averaged only three deer days per acre,” said Watkins.

expertise lies in managing pine plantations for natural

forage regeneration beneficial to wildlife.

“These estimates of nutritional carrying capacity are not meant to be used as absolute values. Specific results may vary with the age of the pine stand and the soil type, but treated areas essentially become natural, high quality food plots,” said Watkins. Nothing was planted in these areas— it’s all natural vegetation that has been in the seedbed waiting for favorable germination and growing conditions. All we do is create the right growing conditions. Fire, sunlight and the seedbed do the rest.”

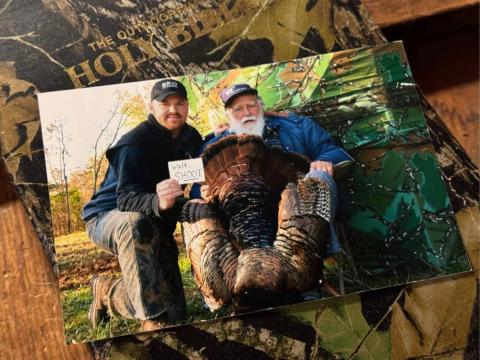

Watkins’ research focuses on results for white-tailed deer, but there are benefits to other wildlife as well. “QVM treated areas provide high quality forage and cover for deer, but also benefit many other species. Turkeys find bugs, seeds, and tender vegetation in these areas. They also use these areas for nesting and rearing young. Quail, rabbits, song-birds and many other animals find these areas very attractive,” said Watkins.

Brian Grice

Brian Grice is a technical assistance biologist with the Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources. He advises landowners on how to best manage their acreage for wildlife.

“Prescribed fire is a major tool I use on any property that consists of planted pines,” said Grice. “Fire does several things and when applied post-thinning, the results are dramatic. Alabama soils are not known for their richness unless you are in the “Black-belt.” Older plants assume the quality of the soil and become undesirable to wildlife for food and eventually shelter. When pines are burned the nutrients trapped in the layers of straw and duff are released. It’s almost like a big shot of natural fertilizer.”

“After pines are thinned, sunlight reaches the ground. Seed scarification by fire increases germination. When spring green up begins the ground literally explodes with tender new plants that have been dormant in the seed bank waiting for proper growing conditions,” said Grice.

“These naturally occurring plants offer good nutrition for deer and turkeys. As they grow they provide nesting and rearing cover for quail and other ground nesting birds. The lush new growth provides high protein browse for deer and attracts insects sought by turkeys. It is a win/win situation.”

“Deer naturally know which plants are most nutritious. They also know that the best browse is the tender twigs, shoots, and buds. These are abundant in pines after a burn. It’s almost like a “natural food plot.” Many landowners plant summer food for wildlife and there is nothing wrong with that, it’s just expensive when compared to fire. On average a prescribed fire costs around $25 per acre.”

“Depending on tree size and basal area of trees, I recommend a two to three year rotation of burns. If you go much longer than that you run the risk of unwanted trees and shrubs escaping to a height where fire cannot control them. You want to horizontally manage the understory or the height of the understory,” said Grice.