Dan Vastyan

Big mountains are no joke. Altitude does funny things to the human body. And sometimes not so funny.

The brain can actually swell, grow soft and basically flood, in the case of high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE). Symptoms start with dizziness, vomiting, and can progress to coma and death. Luckily, if caught soon enough, the only medicine needed is lower altitude. Go down.

High-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE) is similar, though the site of fluid accumulation is the lungs. Profuse sweating, clammy-looking skin and anxiety are all telltale signs of the ailment early on. If you don’t heed those, the bloody coughing should be evidence enough. And it will kill you. Go down.

Hypoxia, as I understand it, is a broader term encompassing a variety of problems. But generally speaking, it refers to a lack of enough oxygen in the blood stream to sustain normal bodily function. It rears its ugly head in a number of different ways, but sometimes acute mountain sickness is the first step. Other times, the sufferer feels dizzy, drunk or stupid.

Maybe you’ve heard of these ailments and others in books and movies about Everest and K2. Lack of atmospheric pressure and low oxygen levels are the biggest hurdles on the world’s highest peaks. So they’re not of any concern for elk hunters, right?

Well, not too often, but you need to be aware of the dangers of hunting high in elk country, not to mention sheep and goats. These sicknesses don’t often set in under 8,000 or 10,000 feet above sea level, but there are plenty of cases in which edema has stricken healthy adults as low as 4,500. And, I’ll add that it’s very random. Altitude might not bother a hunter on nine trips and on the tenth, for no apparent reason, it can come crashing in like Hurricane Katrina.

I’ve dealt with mild altitude sickness and splitting headaches in the past. But last week, in Colorado, I had my first real brush with hypoxia.

Knock off a 14er

If you live under 4,000 feet, you might not know how well you’ll preform “at altitude.” Topping out on a 14er (a mountain over 14,000 feet) is a great litmus test, and Colorado is ripe with them; there are 53 in the Centennial State to be exact. On the peak of a 14er, the “effective oxygen” level is nearly half what’s available at sea level.

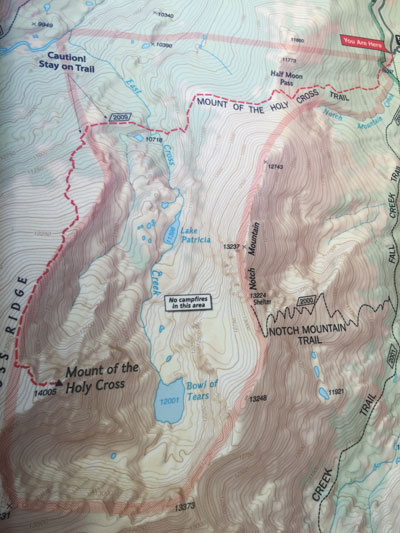

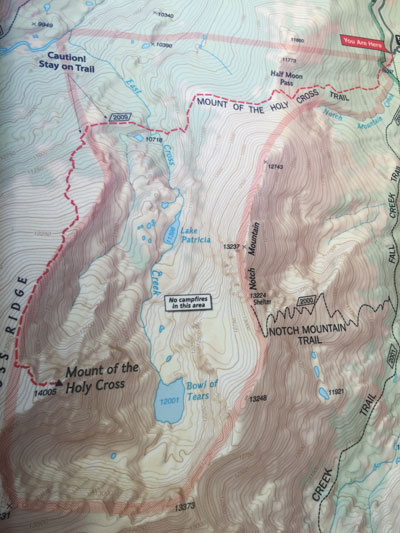

When I learned that work was taking me to Colorado this summer, I hastily made plans to climb two 14ers while there. A friend, Wayne, decided to join me, and we scabbed together an itinerary while researching routes on www.14ers.com. The plan was to summit Ellingwood Point in the Sangre de Cristo Range, roll out of the mountains for a hot shower and some real coffee the day after, and continue up to Mt. of the Holy Cross in the Sawatch Range.

The route we chose on Ellingwood was 11.6 miles round trip, started at 9,600 feet above sea level and offered 5,900 feet of vertical gain. We each had a 35-pound pack, comprised mostly of camping gear, food and lots of water.

First Day Slog

For me, the first day in the mountains after being back East is always the worst. I’m almost always sucking wind, and a bloody nose and tight headache are common. Asprin and L-Arganine help. This time though, I felt great. We set off from the trailhead at quite a pace and pitched camp at dark.

The next morning we kept plowing up the trail, ripping a few Clif Shot Bloks every now and again. At 11,000 feet, now really feeling the altitude, we stopped for a snack of Mountain House meals next to a turquoise blue lake. I shared mine with a marmot. Wayne had packed some ghost pepper powder to mix with our freeze-dried stroganoff, so before long we were steaming up the mountain again.

The next morning we kept plowing up the trail, ripping a few Clif Shot Bloks every now and again. At 11,000 feet, now really feeling the altitude, we stopped for a snack of Mountain House meals next to a turquoise blue lake. I shared mine with a marmot. Wayne had packed some ghost pepper powder to mix with our freeze-dried stroganoff, so before long we were steaming up the mountain again.

At 12,000 and hiking hard, we were both breathing at near sprint levels. From there, Wayne started falling behind. I’d be lying if I didn’t say I enjoyed the break every time I stopped and waited for him. But by 12,500, it was apparent that he was suffering from more than just cardio exhaustion.

As he caught up the last time, I told him to stay put while I peeked around the next corner. Seeing that we still had too far to go, and with a good bit of route-finding to boot, I went back to meet him. By this time, the wind was gusting at 30 or 40 MPH, and I figured the afternoon storms weren’t far behind. And Wayne wasn’t looking so good.

Getting high

“I feel drunk,” he said. “I’m lightheaded, and my feet aren’t going exactly where I tell them to. I feel…. stupid, like…."

Wayne was suffering from hypoxia. His brain wasn’t getting enough oxygen. Having wrestled in high school and raced motocross, he’s a tough dude. He wasn’t making it up, and we needed to go down. With the real crux of the climb still above us, the danger was increasing and his condition was degrading.

We drank more water and made for the lower part of the marmot-infested valley in which the lake lies. This time, we side-hilled above the trail to make a more gradual descent and get off the boulder field. A rolling alpine meadow eventually led us back to the cairned main trail a mile or so below the lake.

Miles slip by quickly when you’re losing elevation, and we made it all the way out to the trailhead in the early afternoon. We only stopped to gulp water from Nalgene bottles. Wayne’s conditions gradually lessened. His headache persisted even after the dizziness passed. We crashed in Buena Vista that night. After a decent night’s sleep and a massive, smothered breakfast burrito, we were ready to attempt Mt. of the Holy Cross.

Summit II

Summit II

On the highway coming north, we’d gotten a fantastic look at Notch Mountain, which really got our blood pumping. The ragged crest of the 13er shrouds any roadside view of Holy Cross.

As we flogged our Hyundai up the dirt road to the trailhead for the Holy Cross, not far from Red Cliff, Colorado, we contemplated everything we wouldn’t need on the climb ahead. We hit the trail with slightly lighter packs. Making real time, we stopped three miles into our journey and picked an epic campsite to crash.

At first light, swarms of mosquitos be damned, we pushed for the summit. Following a well-cairned trail, we hit 13,800 rather quickly. At this point, the journey turned into a scramble. Both hands and feet were needed to ascend the final boulder field that made up the last 300 vertical feet. Now 35 degrees cooler and with wind gusts nearly throwing us off the side of the mountain, we could taste the summit. By the time we tagged the peak, it had taken us just under three hours to gain the last 3,300 feet.

What we failed to consider at the time was that, despite being substantially higher and moving at a better pace, Wayne never felt any symptoms of hypoxia on the second summit. On the contrary, we both felt markedly stronger than before.

I attribute that to a few things:

- If you’re hunting at elevation, the longer you’re in that atmosphere before exerting yourself, the better. A day or two can make all the difference.

- Lighten your load. An ounce in the morning is a pound at night. Be brutally honest with yourself about what items are absolutely necessary to have in your pack. Ditch the rest.

- Hydrate. We were drinking a good bit on the way up Ellingwood Point, but not as much as we did on Holy Cross. In the two and a half hours of our summit push, we consumed nearly five liters.

Summit II

Summit II