By Lee Atkins and Scott Vance

Like a “thief in the night,” cogongrass slipped into the southeastern United States and rapidly spread across the landscape, destroying wildlife habitat and plaguing land managers. The invasion of cogongrass has quickly replaced lack of frequent fire as the greatest threat to ecosystem health and land values in many Southeastern states. Fire, in fact, actually makes cogongrass a bigger threat to habitat by making easier for cogongrass to invade a forest, so this plant is one that landowners should not burn but eradicate with herbicides.

Cogongrass seed was accidentally introduced into Alabama near Grand Bay around 1911, as a stowaway on packing materials from Japan. Approximately 250,000 acres of land in Alabama, Florida and Mississippi are now infested.

Cogongrass forms dense, persistent and expanding stands that displace other vegetation. Its abundant biomass kills competing native plants and changes the properties of litter and upper soil layers.

In the unique Sandhill communities of the Southeast, cogongrass destroys the habitat of rare species such as gopher tortoises and indigo snakes. It is also extremely flammable and greatly increases fuel loads, making fires hotter, higher, potentially more frequent and extremely destructive, even in fire-dependent communities like longleaf pine.

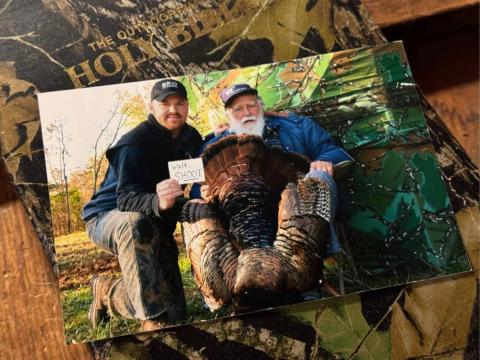

Cogongrass degrades habitat quality for wild turkeys by forming a dense mass that poults, and sometimes adult birds, cannot navigate. However, the loss of benefits from prescribed fire is much more detrimental to wild turkey and other upland game bird habitats. Based on its negative impact on native ecosystems and economically important land management practices, cogongrass is ranked as one of the top 10 worst weeds in the world.

How to stop the spread

The spread of cogongrass is often compared to a forest fire. Just like fighting a forest fire, the first step is setting up a fire-line to stop the advance. Focus all available resources on the leading edge of the fire with an emphasis on protecting unique or rare areas, such as endangered plant communities, red-cockaded woodpecker colonies or gopher tortoise burrowing sites.

The spread of cogongrass is often compared to a forest fire. Just like fighting a forest fire, the first step is setting up a fire-line to stop the advance. Focus all available resources on the leading edge of the fire with an emphasis on protecting unique or rare areas, such as endangered plant communities, red-cockaded woodpecker colonies or gopher tortoise burrowing sites.

Next, find a reputable contractor who understands how to deal with cogongrass. There are many contractors certified to apply pesticides, but few have the experience on non-native plant control and management, especially cogongrass.

A contractor that will be successful in providing effective cogongrass control will:

- Properly scout and identify cogongrass at all stages of growth (not to be confused with similar species like vasey grass, pine-land-three awn, plumegrass, seedling johnsongrass or purpletop).

- Have the ability to use several pieces of equipment and methods on a given site.

- Understand the limitations of the available herbicides, especially on nearby sensitive species.

- Schedule multiple audits and re-treatment intervals that are critical to eradication.

- Guarantee their work based on the percentage of long-term control achieved.

Landowners should look at experience, professional standing in the industry and available references. Weigh cost against the probability of success.

A collaborative effort is a key in stopping the spread of cogongrass and incentivizing its control. Since cogongrass is considered a tremendous environmental threat, there are cost-sharing opportunities for landowners in most southern states. Most of these grants are available through a qualified contractor who ensures the control methods are effective.

The NWTF plays an integral part in controlling the spread of this space invader. Through grants, agreements and partnerships with state, federal and local agencies, the NWTF has provided critical funding to spray cogongrass on private lands and national forests.

The NWTF also worked through a grant from BASF in cooperation with local Conservation Districts and Progressive Solutions, LLC to control hundreds of acres of cogongrass along the Pascagoula River basin using targeted herbicide applications.