Creating Better Deer Nutrition in the Lab

By Mike Messman

There is good information available to help grow food plots, information on high quality forage varieties, soil testing, fertilization needs and how to plant. Food plots can greatly expand the nutrition available to your herd and increase the carrying capacity of a given acreage. Likewise managers have used supplemental feed to provide nutrition at key times of the year and extend habitat. It seems like most conversations about enhancing habitat for deer are either related to food plots or supplemental feeding. The goal of this article is to consider food plots and supplemental feeding and how through lab analysis we can develop feeding practices that work together to get the best aspects of both.

Doing large scale feeding trials with free ranging deer can be difficult and quite expensive. An alternative to feeding trials is to measure nutrient value of feedstuffs (browse, forbs, food plot forages) in the lab and run digestion simulations to evaluate the nutrient value the deer would gain from the diet they consumed. To start this process samples are taken to the lab to be analyzed for nutrient composition. Moisture, crude protein, fat, fiber, ash, starch, sugar and minerals are chemical tests that can be used to measure specific nutrient composition. We can use these tests to evaluate where we are in terms of meeting the nutrient requirements of the animal for protein, energy, minerals and so on.

A deeper dive into the biology of how the diet gets digested can be attained using digestion simulation, or “in-vitro,” digestibility which is a measurement of the feed or components within the feed. The in vitro process simulates digestion that happens inside the deer. Coupling this type of analysis with nutrient evaluation lets us not only evaluate nutrient supply to the deer, but the digestible nutrients the deer can take in.

A deeper dive into the biology of how the diet gets digested can be attained using digestion simulation, or “in-vitro,” digestibility which is a measurement of the feed or components within the feed. The in vitro process simulates digestion that happens inside the deer. Coupling this type of analysis with nutrient evaluation lets us not only evaluate nutrient supply to the deer, but the digestible nutrients the deer can take in.

Knowing digestibility lets us do a much better job of predicting deer performance from lab analysis of the feed. This in-vitro process involves taking the fluid from the rumen of the deer (the stomach that smells bad if you knick it with your knife) mixing it with buffer, the diet sample to be analyzed, keeping it at body temp (102 to 104o F) in an environment without oxygen and incubating it for a period of time, most often 24 or 48 hours. This can then be used to evaluate digestibility across a group of feed samples.

For example, several food plot varieties can be evaluated for crude protein content and in-vitro dry matter digestibility to pick out what will make the most nutritious mix. Let’s talk about extending this further. We can use the in-vitro system to evaluate what types of supplemental feeds will work best in conjunction with habitat and food plots. Stop and think a minute, this could be a pretty powerful tool to fine tune the nutritional package the deer gets from all of its available feed resources.

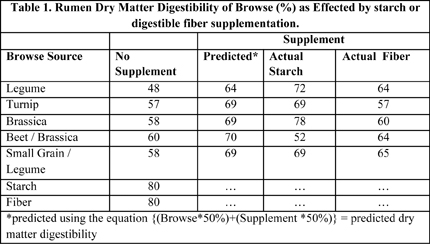

With these concepts in mind, we have started on some preliminary experiments on matching supplemental feed with different food plots. For these initial experiments we have taken different browse species that are commonly used in food plots and evaluated how providing energy in the form of starch or a highly digestible source of fiber would affect the rumen digestibility. To do this we looked at rumen digestibility of the browse alone, the starch or the fiber source alone and then looked at 50:50 mixes of browse source: starch or browse source: fiber (Table 1). To make this comparison simple we looked at starch and fiber sources that had the same dry matter digestibility in the rumen. Remember that when feeding a deer, we are feeding the “bugs” in the rumen to maximize their ability to break down the feed that a deer consumes while it is in the rumen.

One of the goals of this experiment was to see if with unique browse sources the bugs in the rumen would respond differently to starch as an energy source or fiber as an energy source. As we look at the data in table 1, we see that with no supplementation the dry matter digestibility of the browse sources ranged between 48 and 60% dry matter digestibility. The rumen dry matter digestibility of the starch and fiber source was 80% for both. So now if we make 50:50 mixes, browse: starch or browse: fiber, we can calculate mathematically what the dry matter digestibility should be. This calculation is shown in column 2 of table 1 in the predicted dry matter digestibility. For example, starch times 50% + browse times 50% = total predicted rumen dry matter digestibility.

For the first browse sample in table 1, legume, this would be (80*50% + 48*50% = 64% rumen digestibility. Now for the interesting part, when we actually run the experiment we see that math is not all it is cracked up to be. With some browse we get higher than predicted dry matter digestibility and with one we do not do as well. Also, the source of energy that is best depends upon the browse source. Notice that the legume worked better with starch than digestible fiber. When starch was mixed with the legume we got 72% dry matter digestibility, while with the fiber we got spot on with the predicted 64% dry matter digestibility.

In simple terms, on the starch treatment we took 1 + 1 and got 4 while the math on the fiber treatment was 1+1 = 2. This response to the starch over what was predicted is called a “positive associative effect,” when the two things together work better than either of the two apart. If you look at the comparison when the browse source was small grain / legume, fiber worked better than starch as the supplement. In this case starch actually hurt the dry matter digestibility. This type of work needs some refinement but it shows that it should be possible to work out what you are supplemental feeding to work in conjunction with specific food plot crops to improve nutrition of the deer, especially for those looking to grow trophy bucks. It may also be possible by blending different amounts of nutrients like fiber, starch and sugar that products could be developed to work well across a wide variety of browse. More work of this type can lead to improved deer nutrition resulting in improved performance.

Inset photo credit: Dreamstime.com | Tony Campbell